Editor’s Note: Cory Martin is the author of six books including the memoir “Love Sick” which chronicles her life with chronic illness and the best-selling “Yoga for Beginners.” Her work has appeared online with Psychology Today, Everyday Health, MindBodyGreen Folks, and others. She is a lupus and multiple sclerosis advocate. The views expressed here are hers. Read more opinion on CNN.

I am sitting at my desk in a furious rage. Recently I read an article in ProPublica in which pharmacists described “unusual and fraudulent” prescribing activity for the drug hydroxychloroquine, suggesting that doctors may be hoarding it in a “just in case” manner. Not long after that, another article popped up in my Facebook feed, describing a 45-year-old woman with lupus who said she was denied a refill on her hydroxychloroquine at Kaiser because all supplies had been diverted for the “critically ill with Covid-19” who might fill their system. As for her? According to Buzzfeed, the woman was told she could manage for 40 days without the drug and thanked her for her “sacrifice” and “understanding.”

The Lupus Foundation of America has written to Congress and is fighting on our behalf to ensure the drug supply remains strong, but as it is with every bit of this situation, I know that it’s going to take all of us together to find the solution. Together we must not get lost in the panic. We must not forget that everyone is affected by every choice that’s made. And we absolutely must understand that hoarding and withholding hydroxychloroquine will do more harm than good if we’re not careful.

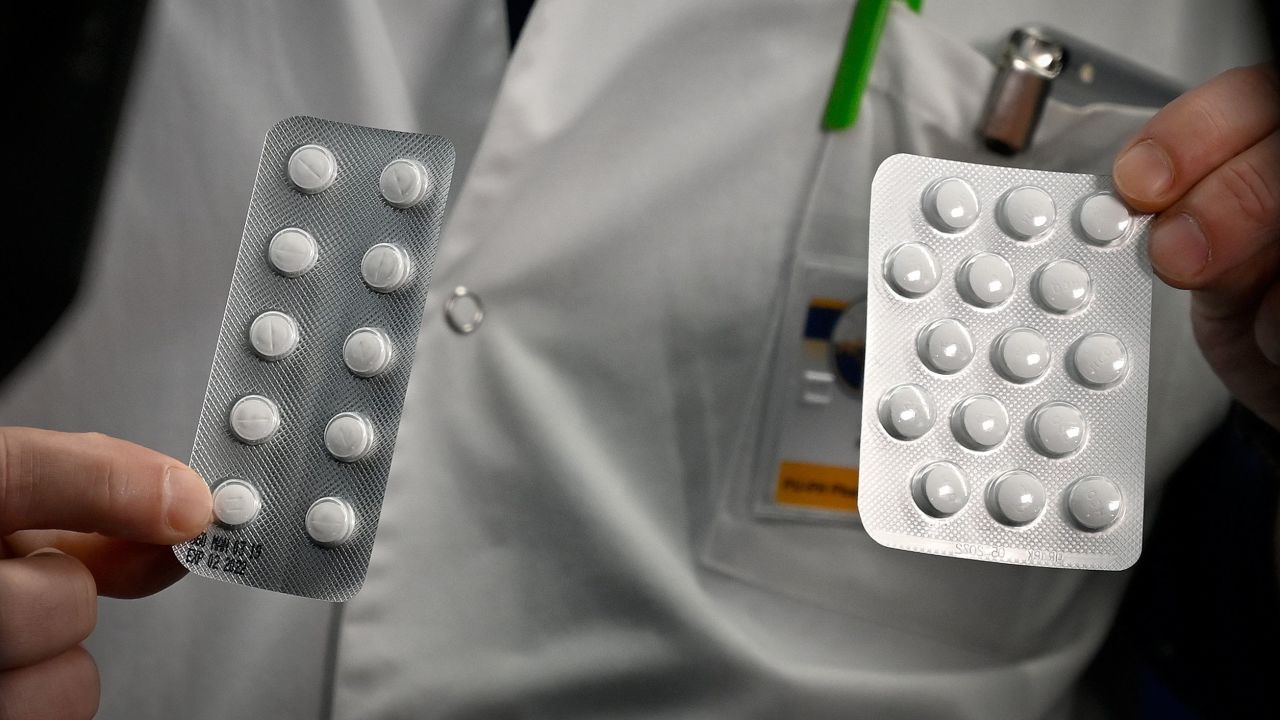

Plaquenil, or the generic version hydroxychloroquine, is an anti-malarial that acts as a disease-modifying drug for those with lupus, like me, and other rheumatic diseases. People who don’t have these diseases want access to hydroxychloroquine because the US Food and Drug Administration has issued emergency use authorization for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to treat patients hospitalized with Covid-19 – and even though there is little scientific evidence that either drug is effective in treating the disease, people are frightened and want to believe it will help. Promising trials are under way, but there is no absolute yet. What is absolute is what will happen to me without the drug. I can tell you, as another woman with lupus, skipping a dose or two of the drug has had serious consequences to my health. I could not make it without for 40 days.

I am scared, too. Scared for myself and the estimated 1.5 million Americans (according to the Lupus Foundation) who also suffer from lupus. Decades ago, before lupus patients had access to this drug, many of them died young. Life expectancy was low. The novel coronavirus isn’t like the flu, it’s far deadlier; the same is true with lupus.

It’s easy to forget about those of us who live with this often-invisible illness because our faces aren’t out there. Stories of our disease don’t haunt the public on a daily basis as is the case currently with Covid-19, but truthfully there are crucial similarities between people like me and the patients with this new diagnosis.

When the symptoms worsen, they will fear death. When they have to adjust to a new normal, they will go through all the stages of grief. When I read stories of people who have gone through a Covid-19 diagnosis, I latch on to phrases like, “wearing the same pajama bottoms for days because it is too hard to change out of them, too hard to stay that long on his feet,” because phrases like that distinctly describe exactly what it’s like when my lupus flares.

I have skipped meals with my fiancé because the thought of having to chew my food was too exhausting. I have cried in the shower because I don’t have the strength to wash my hair. I have missed deadlines and nearly lost jobs because I cannot focus.

Without hydroxychloroquine I would certainly slip back into the far worse state that I was in before I was diagnosed with lupus. It was a state that not only had me fatigued but also riddled with pain. My joints ached. My bones hurt so deeply that I wanted to crawl out of my own skin. My lungs were inflamed, struck with pleurisy that made breathing painful. I became out of breath walking from one room to the next. Changing clothes and talking on the phone left me breathless. I lost my ability to exercise. A walk around the block, if I even had enough strength to complete it, felt like running a marathon. If I spent any time in the sun, I broke out in strange rashes, the fatigue worsened and the bone pain tightened its grip. This was the decline that happened over three months before I was officially diagnosed, before I was on hydroxychloroquine.

Now, imagine if I am denied a refill of the drug and I slip back into that state. Imagine I also contract Covid-19. What then? Am I hospitalized alone, gasping for my last breaths?

I know that we have all played the scenario in our heads about what would and could happen if we got the virus. We understand the best-and-worst-case scenarios. Now imagine if you were contemplating best-and-worst case with Covid plus another disease. With lupus I’m already at a 50% higher risk for heart attack than the general public. Over my lifetime, there’s a 60% chance that my lupus will affect my kidneys which could in turn require chemotherapy, or worse, a transplant. I am fighting for my life daily. Yet, I am one of the lucky ones. I am currently doing quite well. The days of pain and extreme fatigue are spread out amongst the months instead of daily. I can work out again. I have taken on more work. I am managing and feel fairly strong. But do you know why I’m doing well? Because I have been taking my hydroxychloroquine for a little over two years now. If that goes away, then so does my health.

Right now, I am one of the lucky ones whose last routine rheumatologist appointment happened to be before all of this chaos. My prescription is filled, but it will run out and when it does, what will happen then? I can tell you that the fallout from lupus patients without their lifesaving meds will place a bigger burden on our already burdened healthcare system. I can tell you what it will feel like inside my body, and I can tell you that the good from hoarding the drug will not overcome the bad from what occurs when the drug is not available to those who need it most.