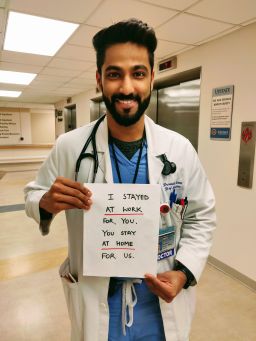

Editor’s Note: Prateek Harne is a resident physician in internal medicine at SUNY Upstate Medical University, in Syracuse, New York. The opinions expressed in the commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion on CNN.

“I am very scared,” my patient said, as my heart raced. She wasn’t the only one.

As I write this, the coronavirus pandemic has reached more than 580,000 cases worldwide, the United States has surpassed China with the most cases, and it’s still rising.

I am a resident physician working at SUNY Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, New York. I was mentally prepared to see these cases in our hospital, but roughly two weeks ago, when I did — in the context of what we know about this virus so far — it left me changed.

As a doctor, we are trained to listen calmly and to understand and validate our patient’s anxiety. Through numerous encounters, we are equipped to handle these situations so that our patients feel acknowledged and relieved after we have had a conversation with them.

But every now and then there comes an interaction that leaves an indelible impact.

My first encounter with a Covid-19 positive patient is something I will never forget. She had been admitted three days earlier, and I was asked to evaluate her, as her oxygen requirements had dramatically increased. As I stood in her room, my heart was racing. I didn’t quite realize it in the moment, but I was scared.

With a distinct heaviness in her breath, she told me how nice everyone has been to her in the hospital. I thanked her. After examining her, I told her that we would need to intubate — insert a tube into her airway — for her to breathe better, and she replied by telling me she was very scared. I held her hand and told her it takes courage to do what she was doing.

She asked me to call her husband, who was being quarantined at home after testing positive, and tell him that she loved him a lot. I did what she asked, and he asked me if I could tell her the same.

Four days later, she passed away due to severe respiratory failure, despite maximal medical supportive therapy. When I learned this, I went from being anxious to scared and then eventually subdued. I believe my anxiety came from three causes: The clinical unpredictability of the disease, its high transmissibility and, more importantly, not being able to alleviate my patient’s distress.

Ever since then, every time I have entered a patient room with a potential Covid-19 infection I have felt scared — scared that I will infect other patients, my colleagues or my loved ones.

Health care providers internalize — and even forget — the emotional toll the job can take. If you meet any of us in the hallway, you may forget for a moment that we are in an ongoing pandemic. We walk into work, smiling, calm and composed. My days off are spent dispassionately debunking myths about this virus with my family and close friends.

We all portray a version of ourselves to the outside world, one that is undeterred by the uncertainty associated with this pandemic, even as we all know that we are scared.

This act of gallantry comes at a deep personal cost. The heaping emotions chip away little parts of you without your even knowing, leading to suppressed turmoil and eventually — for some — burnout. We do not show our vulnerabilities to the world, as we believe that doing so would evoke more panic to those on the outside.

It is completely justified to be overwhelmed. But we know that panic and chaos can never side with you when you are managing a dying patient, or a pandemic for that matter.

During these times, we find ourselves going back to something that makes us human. Something unrelated to this pandemic that threads us together. From singing songs in balconies, like many of those housebound in Italy did to cope and show solidarity, to donating to hospitals, to offering help to health care providers, to staying at home and maintaining social distance, all of this tells us that each one of us is doing our part. I find my salvation in writing.

Get our free weekly newsletter

There is a lot to worry about amidst the increasing incidence, high transmissibility, non-conclusive treatment modalities, potential scarcity of personal protective equipment, crashing economy and unemployment that this world is facing — that you and I face. But if we take one day at a time, calmly focus on our role in this fight, then we might be able to see the light at the end of this tunnel, and probably soon.

I am a soldier in this battle, I am fighting my piece, and I ask you to fight yours. Breathe and keep fighting.