Editor’s Note: This CNN Travel series is, or was, sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over subject matter, reporting and frequency of the articles and videos within the sponsorship, in compliance with our policy.

“This fire has burned 4,000 years and never stopped,” says Aliyeva Rahila. “Even the rain coming here, snow, wind – it never stops burning.”

Ahead, tall flames dance restlessly across a 10-meter stretch of hillside, making a hot day even hotter.

This is Yanar Dag – meaning “burning mountainside” – on Azerbaijan’s Absheron Peninsula, where Rahila works as a tour guide.

A side effect of the country’s plentiful natural gas reserves, which sometimes leak to the surface, Yanar Dag is one of several spontaneously occurring fires to have fascinated and frightened travelers to Azerbaijan over the millennia.

Venetian explorer Marco Polo wrote of the mysterious phenomena when he passed through the country in the 13th century. Other Silk Road merchants brought news of the flames as they would travel to other lands.

It’s why the country earned the moniker the “land of fire.”

Ancient religion

Such fires were once plentiful in Azerbaijan, but because they led to a reduction of gas pressure underground, interfering with commercial gas extraction, most have been snuffed out.

Yanar Dag is one of the few remaining examples, and perhaps the most impressive.

At one time they played a key role in the ancient Zoroastrian religion, which was founded in Iran and flourished in Azerbaijan in the first millennium BCE.

For Zoroastrians, fire is a link between humans and the supernatural world, and a medium through which spiritual insight and wisdom can be gained. It’s purifying, life-sustaining and a vital part of worship.

Today, most visitors who arrive at the no-frills Yanar Dag visitors’ center come for the spectacle rather than religious fulfillment.

The experience is most impressive at night, or in winter. When snow falls, the flakes dissolve in the air without ever touching the ground, says Rahila.

Despite the claimed antiquity of the Yanar Dag flames – some argue that this particular fire may only have been ignited in the 1950s – it’s a long 30-minute drive north from the center of Baku just to see it. The center offers only a small cafe and there’s not much else in the area.

Ateshgah Fire Temple

For a deeper insight into Azerbaijan’s history of fire worship, visitors should head east of Baku to Ateshgah Fire Temple.

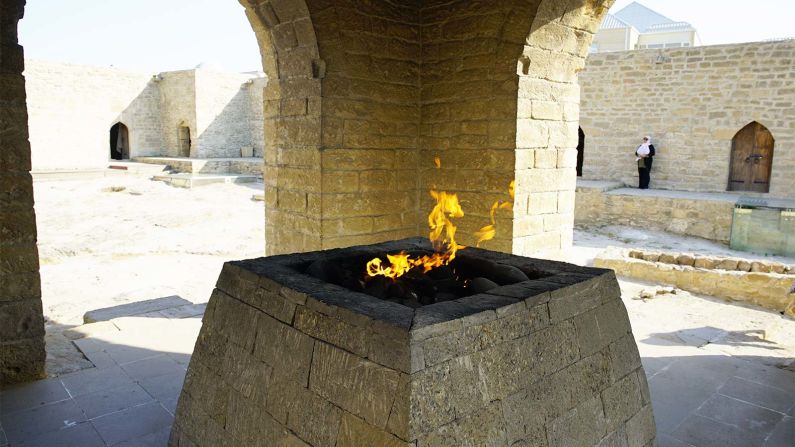

“Since ancient times, they think that [their] god is here,” says our guide, as we enter the pentagonal complex which was built in the 17th and 18th century by Indian settlers in Baku.

Fire rituals at this site date back to the 10th century or earlier. The name Ateshgah comes from the Persian for “home of fire” and the centerpiece of the complex is a cupola-topped altar shrine, built upon a natural gas vent.

A natural, eternal flame burned here on the central altar until 1969, but these days the fire is fed from Baku’s main gas supply and is only lit for visitors.

The temple is associated with Zoroastrianism but it’s as a Hindu place of worship that its history is better documented.

Merchants and ascetics

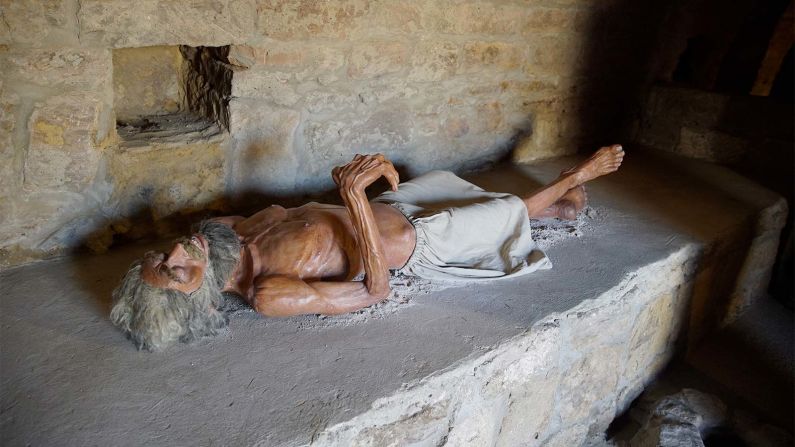

Built like a caravanserai-style travelers’ inn, the complex has a walled courtyard surrounded by 24 cells and rooms.

These were variously used by pilgrims, passing merchants (whose donations were a vital source of income) and resident ascetics, some of whom submitted themselves to ordeals such as lying on caustic quicklime, wearing heavy chains, or keeping an arm in one position for years on end.

The temple fell out of use as a place of worship in the late 19th century, at a time when the development of the surrounding oil fields meant that veneration of Mammon was gaining a stronger hold.

The complex became a museum in 1975, was nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998, and today welcomes around 15,000 visitors a year.