Sumo wrestling is as ingrained in the culture of Japan as sushi and cat cafes.

Alas, those eager to catch a match might be out of luck, as ticket prices are high and the tournament season is sporadic and short-lived – there are only six tournaments per year throughout the country.

The good news is, with a little forward planning, visitors to Tokyo can get closer to a sumo wrestler than they ever would at a tournament. So close, in fact, they can even smell their sweat.

Inside a sumo wrestler’s house

Sumo: Can Japan's national sport survive?

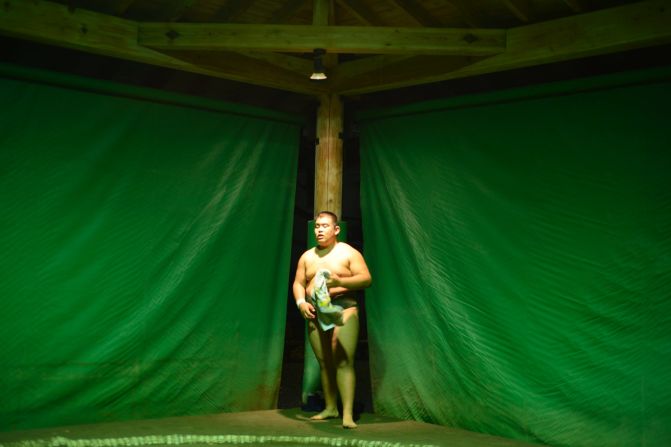

When they’re not competing, sumo wrestlers train year round in designated sumo stables, or beya.

These stables, which are mostly based in Tokyo’s Ryogoku neighborhood, are where the city’s wrestlers live, eat, sleep and practice on a near daily basis. In recent years, it’s become more common for foreigners to visit the morning practice, which begins at about 5 a.m. and lasts three to four hours.

Not all stables appreciate visitors, however, and none enjoy people showing up unannounced.

Mark Buckton, editor of Sumo Fan Magazine and the sumo columnist for Japan Times, says it’s essential to get a Japanese speaker to call ahead the day before to make sure it’s OK to drop in. You can usually get the hotel concierge to dial in.

“There are around 12 to 15 stables in that area,” explains Buckton. “Some places just don’t want foreign people turning up and some have signs outside on the door in English.”

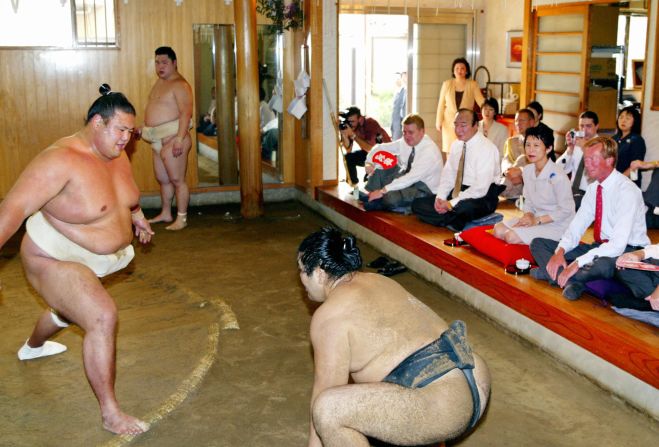

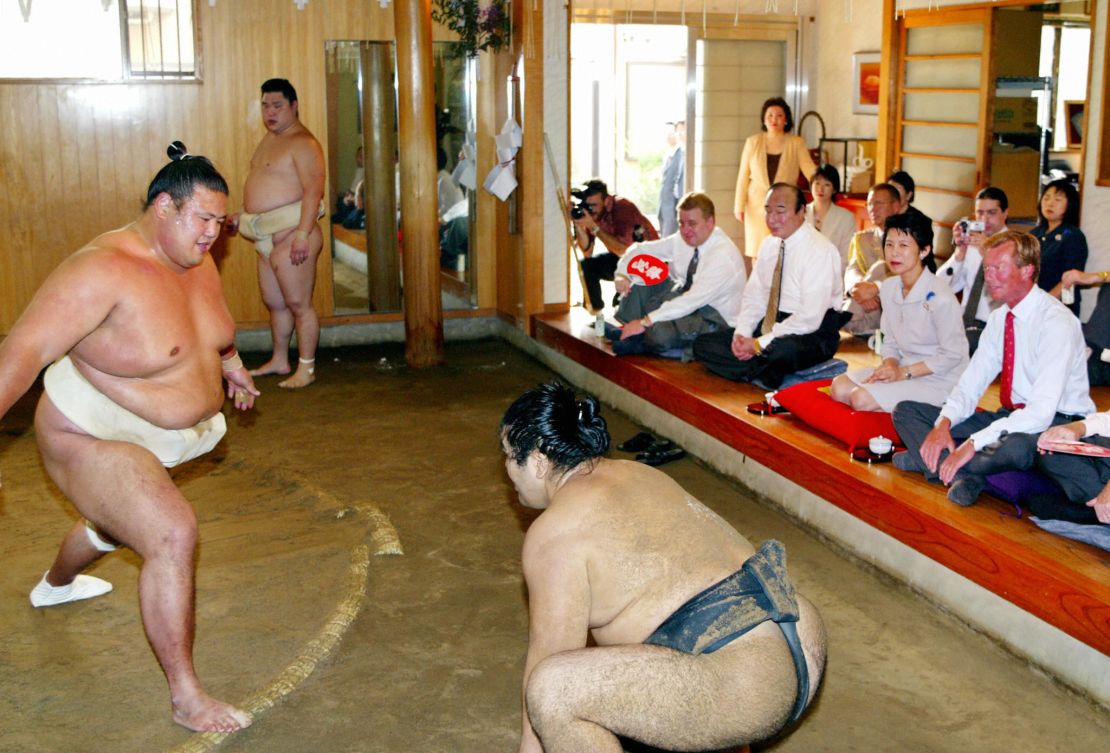

Unless you can get ringside seats at a tournament, the morning practice at a sumo stadium is the closest you’ll likely get to a sumo wrestler.

“The proximity of you to the wrestlers, it’s like you’re sitting in a living room, watching people at the opposite end fighting,” says Buckton.

Sit still, don’t say a word

Buckton points out that because the stables are basically the living quarters for the wrestlers and the sumo masters who oversee them, it’s important that visitors show respect. He recalls a time he witnessed two American tourists tell the stable master to stop smoking.

This, he says, is a definite no-no. “It’s their house,” he says. “If I go to your house, I’m not going to ask you to stop doing something I don’t like.”

Because training takes a lot of focus, it’s essential not to distract the wrestlers by talking or moving around a lot.

“You should expect to sit on the floor for two, two and a half hours,” says Buckton. “They might offer you a cushion, they might not. You’re not supposed to move, and that includes going to the toilet.”

“And they will get annoyed if you start speaking.”

As a result, he adds, it’s definitely not a good environment for young children.

Buckton also says that, in keeping with Japanese etiquette, visitors should wear socks or tights, even when in sandals, as it’s customary to remove shoes when entering.

Bare feet are deemed impolite.

In summer, it’s best to wear something that covers up the shoulders. Also, “when you sit on the floor, you should never point the soles of your feet toward the ring.”

Get Instagram likes

Catching a morning training session can result in prime photo ops. The main rules?

Don’t use a flash and mute the shutter sound on your phone.

Otherwise, taking pictures is usually permissible, though Buckton recommends taking one as a test and gauging the reaction of the wrestlers before continuing.

“If you’re leaving near the end of practice, you might see wrestlers milling around outside,” he says. “Go speak to them if you want a picture with the big guys.

“They look scary, but they’re softies, and they’ll almost always say yes.”

What’s it cost?

By and large, the only thing a trip to the sumo stables should cost is the metro fare to Ryogoku.

That said, there are several companies that have popped up in recent years charging exorbitant fees to sit in and watch a practice. Buckton’s advice: Don’t pay.

“Sometimes the stables will have morning practice, finish, then put on a fake practice for tourists,” he says.

“They’ll do a few dramatic throws and charge a couple of hundred dollars to eat with the wrestlers, but that’s gimmicky. It’s not the real world of sumo.”

Furthermore, he says the guides associated with these types of tours aren’t always sumo experts.

“To be a guide means you’re Japanese. It doesn’t mean you know what you’re talking about. I’ve heard them come out with all sorts of BS about what’s happening and tourists don’t know what’s right and what’s wrong.”

Where and when to go

Buckton says the best time to drop in on a session is the last week of December, the first week of January, the last week of April, the first week of May, the last week of August and the first week of September.

“It’s because the tournaments are in January, May and September, and the weeks leading up are a good time to visit,” he explains. “Practice can be quite intense and the wrestlers really go for it.”

As for stables to visit, he says three stand out:

As stables go, Kasugano Beya is one of the oldest in Tokyo.

Though it was inactive for over a century, the stable was founded in the 18th century.

It’s been home to several high-ranking champions, and as such is a good spot to watch some high-level competing.

1-7-11 Ryogoku, Sumida-ku, Tokyo; +81 (0)3 3631 1871

2. Hakkaku Beya

Grand champions are hard to come by in sumo.

According to Buckton, there have only been 71 grand champions in sumo’s 270-year history.

The stable master, Hakkaku Nobuyoshi (formerly Nobuyoshi Hoshi) happens to be one.

Some of the wrestlers at the stable rank in the top 10% of the sport.

You can tell because they wear white belts, as opposed to the lower ranking black belts worn by the majority of wrestlers.

As a result, visitors are all but guaranteed a decent practice.

1-16-1 Kamezawa, Sumjida-ku, Tokyo; +81 (0)3 3621 0505

3. Kokonoe Beya

Like Hakkaku, Kokonoe is also run by a former grand champion, and is home to a couple of white belt champions.

4-22-4 Ishiwara, Sumida-ku, Tokyo; +81 (0)3 5608 0404