It’s not the world’s highest mountain, nor is it the hardest one to climb, presumably.

Famed climber Reinhold Messner never bothered with this obscure peak and it won’t be landing a NatGeo special or an “Into Thin Air” sequel anytime soon.

So why exactly are we nominating Muchu Chhish – a 7,453-meter lump of glacier-flanked rock and ice tucked in a remote valley of northern Pakistan’s Karakoram Range (home to bigger, badder, better-known, 8,000-meter A-listers like K2, Broad Peak and Gasherbrum I & II) – as the latest holy grail of mountaintops?

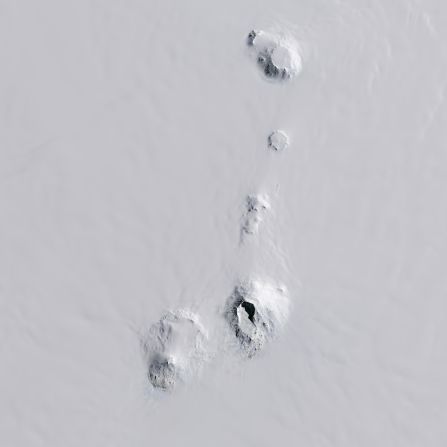

Because among all the numberless and largely nameless mountains that have yet to see a human foot, flag or breathless YouTube post on their standoffish summits, Muchu Chhish is, for all wild and crazy intents and purposes, the highest unclimbed hill on Earth. (See above image)

Only one mountain gets that spotlight at a time, however bright or (in this case) rather faint.

Everest had its lengthy tenure until 1953, when the Himalayan giant and highest point on Earth was first successfully reached.

The world’s second highest summit, K2, was checked off a year later in 1954. Number three, Kanchenjunga, was scaled in 1955. Next up, Mt. Lhotse, the world’s fourth highest peak, was surmounted in 1956. And so on.

Seven Summits: The highest mountain on each continent (photos)

Now it’s Muchu Chhish’s turn. Mighty number 61, or thereabouts. Mountain height rankings start to get hazy around this point. But the natural human ambition to notch that next big first ascent remains as clear and compelling as ever.

“There’s a sort of authorship to any first ascent – like a writer or a painter creating something from scratch,” says American Alpine Institute executive director Jason Martin, who has logged his share of rock climbing firsts in the American West – and hadn’t heard of Muchu Chhish until now.

“I think the biggest and most interesting thing when it comes to first ascents on giant, remote mountains like this one where you’re basically an astronaut is just that – reaching this otherworldly spot where nobody else has been. Another element, of course, is the huge added challenge of it because there’s virtually no information on how to do it.”

The world’s highest unclimbed mountain**

Hiding in the Western Karakoram on the Batura Wall – a massive ridge of 7,000-meter peaks looming above one of the world’s largest non-polar glaciers – Muchu Chhish has foiled all attempts by sporadic expeditions to reach its elusive crest over the last few decades.

The barely visited peak (also known as Batura V) has held its own double-asterisked distinction as the highest unclimbed mountain for several years now.

Why the two asterisks in this case?

*Another Asian peak, 7,570-meter Gangkhar Puensum, remains the actual highest unclimbed mountain on Earth at present, but its location in Bhutan (where mountaineering has been prohibited since 2003) means this off-limits summit is respectfully withdrawn from worldly contention.

**There’s a debatable point that Muchu Chhish is technically a secondary peak (or “subpeak”). According to National Geographic, most geologists define a mountain as an independent landform exceeding 300 meters (about 1,000 feet) above its surrounding area.

Muchu Chhish is shy of that prominence, but venerated among very legit Karakoram climbing circles as a bona fide mountain.

All hair-splitting aside, who would really want to deny sufficiently grand-ish Muchu Chhish its provisory status as the highest, permissible unclimbed peak of one sort or another on earth?

Certainly not any outlier alpinist braving its unsolved slopes during a narrow climbing window in late summer.

“There’s still a lot of great unclimbed peaks out there – more than people think – but unless you start playing with definitions Muchu Chhish is really the highest one left,” says alpinist Phil de-Beger, who was part of a three-person UK expedition to Muchu Chhish in August 2014 – already six years ago, but still one of the most recent and few serious attempts on this mountain.

“You’ve got some of the biggest mountains in the world in the Karakoram, and it’s always a real adventure out there,” adds de-Beger, who has logged other first ascents in that area with fellow climbing partners Tim Oates and expedition leader Peter Thompson.

“I get asked about Muchu Chhish all the time by climbers who want that ‘first ascent tick’ on the highest permissible unclimbed peak. But that’s not nearly as interesting as the mountain itself if you ask me.”

What makes climbing Muchu Chhish more interesting than bragging rights?

“It’s the unknown,” de-Beger tells CNN Travel.

“On an unclimbed peak in the Karakoram that hasn’t been mapped out like those overpopulated prize peaks in the Himalayas, it’s essentially still very exploratory. That’s what has really fueled us to go to that area in general, and what keeps us going.”

Until it’s time to turn around.

“About 80% of the deal with these climbs is being lucky”

During the 2014 expedition, the three climbers called it quits around the 6,000-meter mark, well below the summit, upon hitting a long, steep snow ridge that had unexpectedly transformed into a bullet-hard sheet of ice.

“According to what we’d heard from previous expeditions, which had climbed that same ridge (to reach a neighboring peak) in years past, we were hoping to do basic kick steps and it would just be a long slog,” recounts de-Beger.

“But by the time we got there it had essentially become a sustained ice climb. Not super-hard on its own, but also not something we were really prepared for at that altitude and for that duration without being able to put up a camp.”

The surprise tilted ice rink, likely caused by climate change over the years, was presaged by rough, unexpected conditions on the peak right from the start.

After a dramatic commute to the secluded mountain along the precipitous Karakoram Highway and a multi-day trek from the Hunza Valley featuring rowdy yak herds and a glacial labyrinth riddled with rocky crevasses en route to base camp, the three mountaineers had timed their climb for optimally dry conditions.

Instead they got hit with a relentless blizzard.

“When we reached base camp it began snowing very heavily – day after day – which was quite a surprise,” recalls co-climber Tim Oates.

“That area in theory is north of the monsoon shadow so it should be much drier. But we ended up getting snowed in for quite a long time, surrounded by a ring of mountains that were avalanching day and night. Plus all of those dry crevasses were now suddenly covered with snow so you weren’t able to see where they were. That was a slight issue too.

“About 80% of the deal with these climbs is being lucky with the right conditions,” says Oates.

In spite of bad weather and more hard luck on the upper slopes after the skies had finally cleared, the shortened expedition was its own qualified success according to both climbers.

“Hunza is absolutely stunning. Really one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen, and the local people in the surrounding villages could not have been friendlier or more welcoming” says Oates.

“The real highlight was just being there. Being in that environment. The actual trip and the attempt was the goal. If we’d actually gotten to the summit that would’ve been the bonus.”

“I always describe the Karakoram as an even more adventurous version of Nepal without nearly the same level of infrastructure but limitless pure mountaineering potential,” says de-Beger.

“No sherpas to look after you. Just you and the mountain. You’re definitely on your own.

“Our tactics on Muchu Chhish, based on what we thought we knew, weren’t spot on There were a lot of route finding issues and sleeping with half a bum cheek on a rock at 6,000 meters, but that’s all part of it. And that’s why these trips often take a few attempts at least. I’m convinced Muchu Chhish will be climbed – and soon, perhaps.”

A failed August attempt

The latest climbing campaign on the virgin 7,000er happened in August – a scaled down 2020 Czech expedition consisting of three climbers, Pavel Korinek, Jiri Janak and 57-year-old alpinist and politician, Pavel Bern, a former Lord Mayor of Prague and successful Everest and K2 summiter.

“The aim of this year’s expedition will be the highest peak in the world, where the human foot has not yet stood and on which you can legally climb! That’s worth it, right?” touted an early March Facebook post from the original nine-climber 2020 Czech team – shortly before six of them dropped out in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

While expeditions to Nepal’s popular Himalayan peaks, including Everest, were suspended due to Covid-19 during the spring climbing season with recent plans to resume this fall, Pakistan’s far less visited Karakoram has remained open to climbers since May when a nationwide lockdown was lifted.

By late August, the three climbers would be posting “great progress” along the daunting upper ice traverse of Muchu Chhish that had stopped their UK predecessors six years ago.

An avalanche of glum, harrowing Facebook updates from 6,313 meters would soon follow.

“Terribly psycho sleeping on a ledge, half a meter from the hole a mile down. Already three days zero rest. Not a single place for sitting during climbing. We spend today in a tent because of terrible mess outside. Descend tomorrow and prepare for another attempt in few days …”

Soon after that, the expedition officially folded due to more bad weather.

Descending from base camp, the Czech team would pass two more ambitious alpinists – Spanish climber Jordi Tosas and Philipp Brugger of Austria – on their way up, in hopes of becoming the first climbers to reach the top of Muchu Chhish.

Whether the next attempt succeeds or not, or the one after that, Muchu Chhish will no doubt be scaled sooner or later. At which point, CNN Travel will be sure to cordially introduce you to the next highest unclimbed peak you’ve never heard of.

Where does it end?

“I don’t really think that it ever ends,” says AAI’s Martin. “There are just too many unclimbed mountains in the middle of nowhere, let alone new routes up old ones, that every next generation of incredibly talented climbers will be determined to challenge themselves on.

“The real question at this point,” adds Martin, with a laugh, “is whether anybody cares.”