Editor’s Note: Monthly Ticket is a CNN Travel series that spotlights some of the most fascinating topics in the travel world. September’s theme is ‘Build it Big,’ as we share the stories behind some of the world’s most impressive feats of engineering.

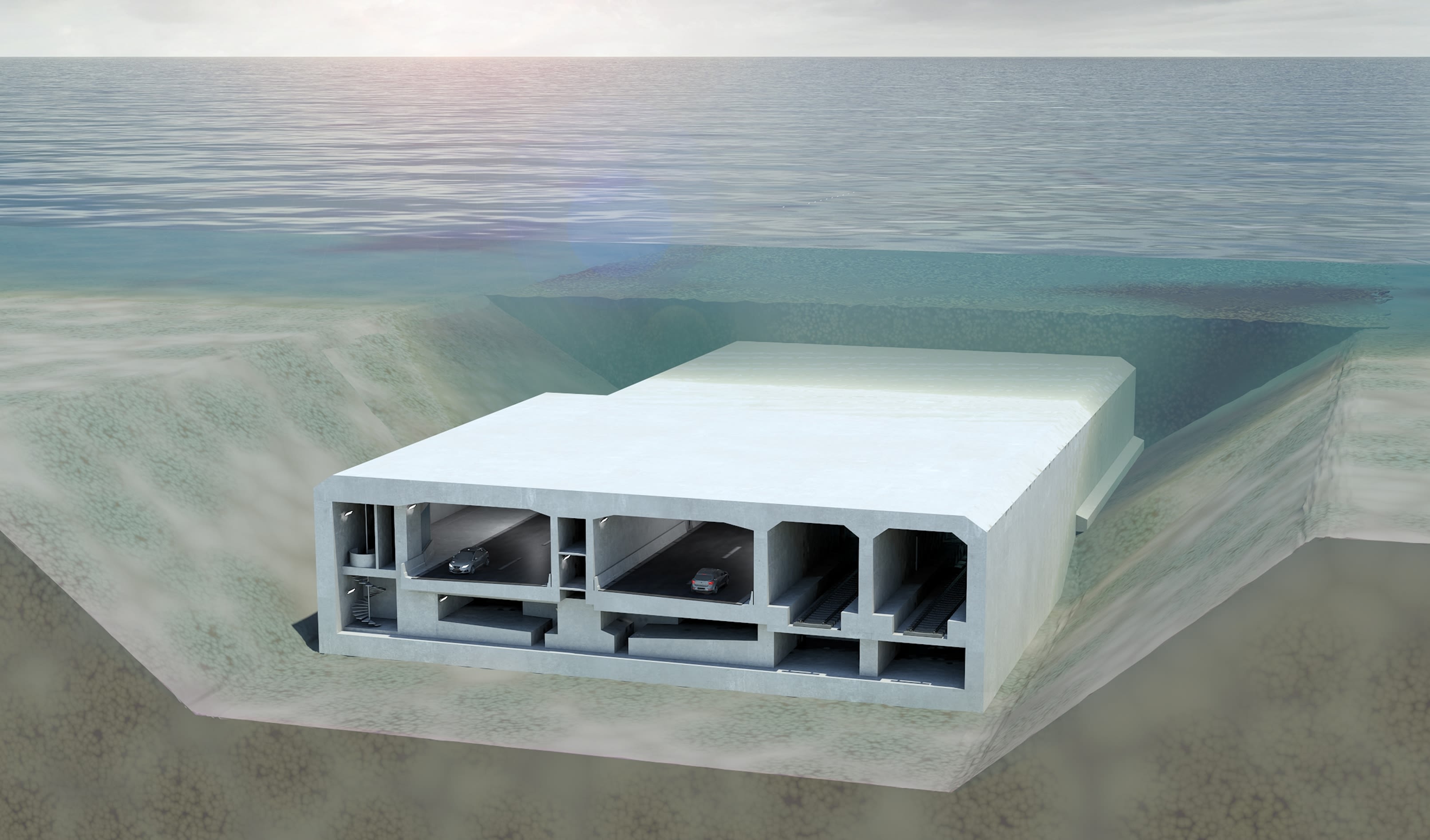

Descending up to 40 meters beneath the Baltic Sea, the world’s longest immersed tunnel will link Denmark and Germany, slashing journey times between the two countries when it opens in 2029.

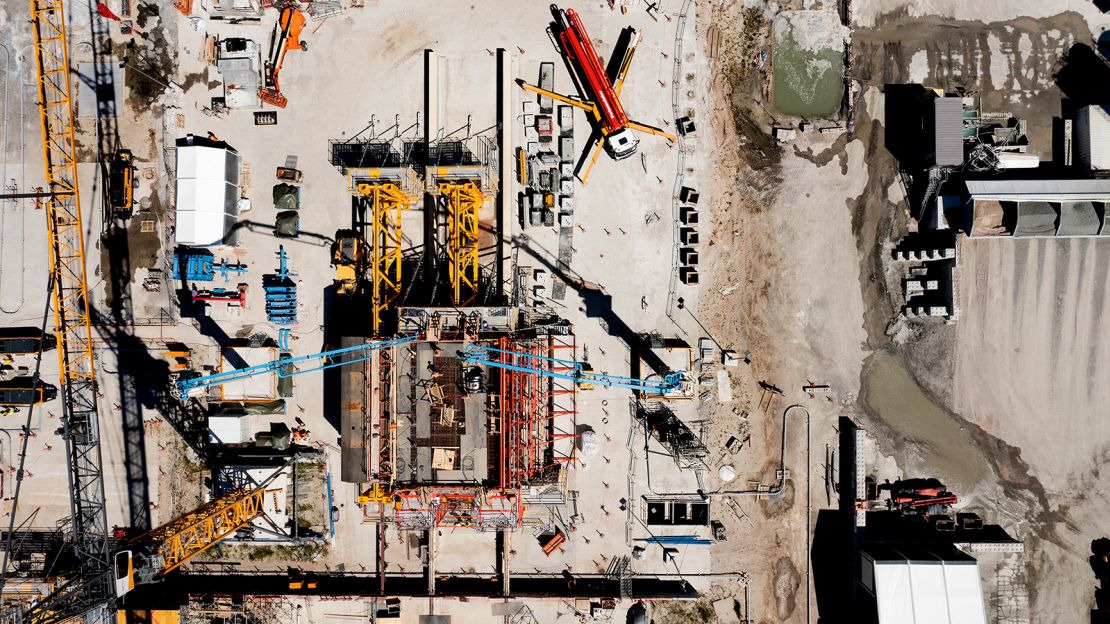

After more than a decade of planning, construction started on the Fehmarnbelt Tunnel in 2020 and in the months since a temporary harbor has been completed on the Danish side. It will host the factory that will soon build the 89 massive concrete sections that will make up the tunnel.

“The expectation is that the first production line will be ready around the end of the year, or beginning of next year,” said Henrik Vincentsen, CEO of Femern A/S, the state-owned Danish company in charge of the project. “By the beginning of 2024 we have to be ready to immerse the first tunnel element.”

The tunnel, which will be 18 kilometers (11.1 miles) long, is one of Europe’s largest infrastructure projects, with a construction budget of over 7 billion euros ($7.1 billion).

By way of comparison, the 50-kilometer (31-mile) Channel Tunnel linking England and France, completed in 1993, cost the equivalent of £12 billion ($13.6 billion) in today’s money. Although longer than the Fehmarnbelt Tunnel, the Channel Tunnel was made using a boring machine, rather than by immersing pre-built tunnel sections.

It will be built across the Fehmarn Belt, a strait between the German island of Fehmarn and the Danish island of Lolland, and is designed as an alternative to the current ferry service from R?dby and Puttgarden, which carries millions of passengers every year. Where the crossing now takes 45 minutes by ferry, it will take just seven minutes by train and 10 minutes by car.

Faster journey

The tunnel, whose official name is Fehmarnbelt Fixed Link, will also be the longest combined road and rail tunnel anywhere in the world. It will comprise two double-lane motorways – separated by a service passageway – and two electrified rail tracks.

“Today, if you were to take a train trip from Copenhagen to Hamburg, it would take you around four and a half hours,” says Jens Ole Kaslund, technical director at Femern A/S, the state-owned Danish company in charge of the project. “When the tunnel will be completed, the same journey will take two and a half hours.

“Today a lot of people fly between the two cities, but in the future it will be better to just take the train,” he adds. The same trip by car will be around an hour faster than today, taking into account time saved by not lining up for the ferry.

Besides the benefits to passenger trains and cars, the tunnel will have a positive impact on freight trucks and trains, Kaslund says, because it creates a land route between Sweden and Central Europe that will be 160 kilometers shorter than today.

At the moment, traffic between the Scandinavian peninsula and Germany via Denmark can either take the ferry across the Fehmarnbelt or a longer route via bridges between the islands of Zealand, Funen and the Jutland peninsula.

Work begins

The project dates back to 2008, when Germany and Denmark signed a treaty to build the tunnel. It then took over a decade for the necessary legislation to be passed by both countries and for geotechnical and environmental impact studies to be carried out.

While the process completed smoothly on the Danish side, in Germany a number of organizations – including ferry companies, environmental groups and local municipalities – appealed against the approval of the project over claims of unfair competition or environmental and noise concerns.

In November 2020 a federal court in Germany dismissed the complaints: “The ruling came with a set of conditions, which we kind of expected and we were prepared for, on how we monitor the environment while we are constructing, on things like noise and sediment spill. I believe that we really need to make sure that the impact on the environment is as little as possible,” says Vincentsen.

Now the temporary harbor on the Danish site is finished, several other phases on the project are underway, including the digging of the actual trench that will host the tunnel, as well as construction of the factory that will build the tunnel sections. Each section will be 217 meters long (roughly half the length of the world’s largest container ship), 42 meters wide and 9 meters tall. Weighing in at 73,000 metric tons each, they will be as heavy as more than 13,000 elephants.

“We will have six production lines and the factory will consist of three halls, with the first one now 95% complete,” says Vincentsen. The sections will be placed just beneath the seabed, about 40 meters below sea level at the deepest point, and moved into place by barges and cranes. Positioning the sections will take roughly three years.

A wider impact

Up to 2,500 people will work directly on the construction project, which has been impacted by the global supply chain woes.

“The supply chain is a challenge at the moment, because the price of steel and other raw materials has increased. We do get the materials we need, but it’s difficult and our contractors have had to increase the number of suppliers to make sure they can get what they need. That’s one of the things that we’re really watching right now, because a steady supply of raw materials is crucial,” says Vincentsen.

Michael Svane of the Confederation of Danish Industry, one of Denmark’s largest business organizations, believes the tunnel will be beneficial to businesses beyond Denmark itself.

“The Fehmarnbelt tunnel will create a strategic corridor between Scandinavia and Central Europe. The upgraded railway transfer means more freight moving from road to rail, supporting a climate-friendly means of transport. We consider cross-border connections a tool for creating growth and jobs not only locally, but also nationally,” he tells CNN.

While some environmental groups have expressed concerns about the impact of the tunnel on porpoises in the Fehmarn Belt, Michael L?vendal Kruse of the Danish Society for Nature Conservation thinks the project will have environmental benefits.

“As part of the Fehmarnbelt Tunnel, new natural areas and stone reefs on the Danish and German sides will be created. Nature needs space and there will be more space for nature as a result,” he says.

“But the biggest advantage will be the benefit for the climate. Faster passage of the Belt will make trains a strong challenger for air traffic, and cargo on electric trains is by far the best solution for the environment.”