In the tropical morning light, Malaysia’s Lake Temengor is a glazed expanse of emerald green, deepened by the dense walls of rainforest surrounding it.

Skimming across the water in a speedboat, we pass a group of indigenous – or orang asli (“original people”) – boys playing on a bamboo raft among deadwoods that rise like silhouettes from the lake’s surface.

It’s an oddly picturesque travel sight, like the remnants of a lost world, made more striking by the highway that bridges the lake.

This body of water is part of Belum-Temengor, a grouping of forest reserves in Malaysia’s Perak state covering an area more than four times the size of neighboring Singapore.

Estimated to be more than 130 million years old, these rainforests date back to a time when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth. They are older even than their counterparts in the Amazon or the Congo.

That Lake Temengor is a more recent invention doesn’t detract from its natural beauty. River-damming in the 1970s turned these hills into mini islands – such as Banding, which is a convenient launching pad to explore the area.

We’re staying at the Banding Island-based Belum Rainforest Resort, which includes a day’s tour to Belum-Temengor’s most pristine swath of forest. Designated the Royal Belum State Park in 2007, logging is prohibited.

The park, located near the Thailand border, is a good alternative if you can’t make it to the jungles of Borneo or want to veer off the well-trodden course this side of Malaysia.

It’s home to about 1,000 indigenous Jahai people and critically endangered animals like the Malayan tiger, which numbers between 250 and 340 in the country and is the current focus of WWF Malaysia’s conservation efforts.

To enter the park, you need a permit and a licensed guide, and the only way to get there is to follow the lake’s waterways north.

Visiting indigenous Jahai villages

It’s a 30-minute boat ride from the resort’s private jetty to the mouth of Sungai Perak, which snakes through the Royal Belum State Park and branches into smaller rivers.

Our first stop is Sungai Gadong to see rafflesia flowers. Said to be the world’s largest bloom, they can grow as wide as a meter and emit a stink likened to rotting flesh.

But it’s a spectacle that takes some luck to catch.

“It takes nine months to mature, and flowers for just five to seven days before dying,” our guide Hafizul Haron says. We only see only one clamped-up orange bud the size of a volleyball among black rafflesia corpses.

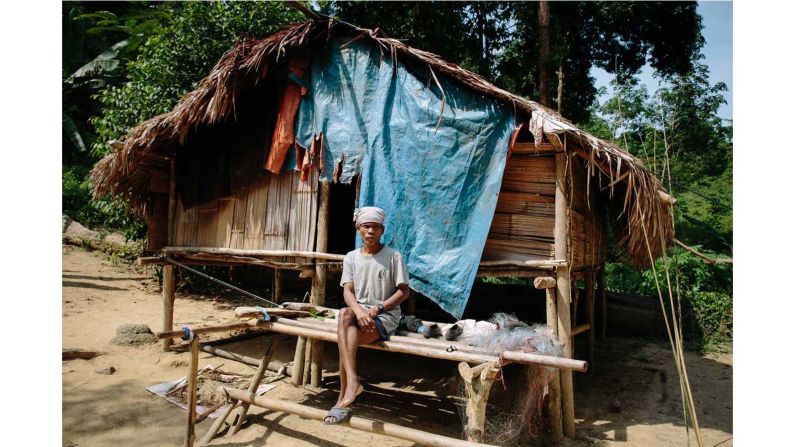

Next, we come to a Jahai village around Sungai Kejar, where eight families live in thatched huts and a generator powers televisions and other modern needs.

Hafizul points out a long rod lying in a boat along the bank.

“That’s a blowpipe, but unlike the traditional ones it’s encased in steel to protect the bamboo. The Jahai use it to hunt small animals like squirrels or birds,” he says.

After Kerji Renjak, the 45-year-old headman, grants us permission to enter his village, he invites us in to sit on the steps of his hut to chat while the women and children cluster around one another, interjecting occasionally, and a monkey dangles playfully from a tree.

He tells us about some of the joys of living here – he likes hearing the sounds the deers make – and some of the challenges.

“The amount of fish in the lake has dwindled due to recreational fishing, and when we grow crops the elephants sometimes destroy them,” he says.

Kerji is welcoming and chatty, but travelers should keep in mind that the Jahai have spoken out about the adverse effects wildlife conservation and tourism have had on their lives.

The orang asli receive gifts and monetary donations from visitors as recommended by guides, and some of them are employed by the tour outfits and resorts. But for the most part, some say they’ve yet to be included more meaningfully in the nascent ecotourism industry here.

Hidden dangers, endangered animals

The Jahai live among Royal Belum’s reputed 10 species of hornbills and endangered mammals like the Sumatran rhino, the Asian elephant, the Malayan gaur and the Malayan tapir, besides the Malayan tiger.

You’re not likely to see the big creatures, but you might spot one of the smaller animals at the Sungai Papan salt lick – a mineral patch teeming with butterflies that wild boars, sambar deers and pangolins frequent to lap up nutrients.

Later, Hafizul leads us for a short hike in the forest among columnar trunks, giant fronds and looping vines, showing us plant life capable of producing all manner of things.

One of the most lucrative is the agarwood-producing tree, locally called gaharu, which yields oils used in perfume, incense and traditional medicine, and fuels an annual global trade worth $6.4 billion.

On our last stop, we navigate into a sheltered cove, where the trees tower above us and bow at one another, forming an imaginary green cathedral. Then we make our way to the Sungai Ruok waterfall, for a reprieve from the heat.

The Belum Rainforest Resort also offers shorter excursions, like a 40-minute night hike around its compound on Banding Island.

The buzz of cicadas and crickets become the sound of silence, and Hafizul’s eagle eyes help us navigate the darkness.

We come across wild boars foraging for food and small but venomous creatures like scorpions, spiders and centipedes. We also see giant ants the size of our thumbs. And don’t forget run-ins with leeches.

Even the plants are dangerous in the dark.

“Don’t touch the bamboo. It’ll make you really itchy,” Hafizul says. “Don’t stumble on the rattan vines. They have spikes that can scratch you.”

Along the way, we pass an old lookout tower from the 1950s, which the Malaysian military used in their fight against the communists, who occupied the region then. (When the hydropower dams flooded the Belum-Temengor forest, the communists were deprived of cover.)

At the end of the hike, we emerge from Lake Temengor’s sloping shores under the East-West Highway, which bisects Belum-Temengor into north and south.

A receptionist at the resort says that if you walk along this highway at night, you might see elephants crossing the road – if you’re lucky.

Planning your visit

Banding Island is 400 kilometers from the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur, and you can only get there directly by car. To break the journey, you can stop in the city of Ipoh, which should be of interest to culinary and cultural travelers.

Compared to other Malaysian destinations, Belum-Temengor is relatively expensive. For convenience’s sake, most people book an accommodation package, which usually includes meals and a tour.

Belum Rainforest Resort offers luxurious rooms and villas overlooking Lake Temengor, and cheaper rooms in its older blocks. It eschews televisions but offers all other facilities you’d typically expect, including WiFi.

For an earthier experience, Belum Eco Resort – located on a separate island south of Banding – offers wooden chalets and dorms with no air-conditioning, and only uses electricity from 6:30 p.m. to 8 a.m. However, you’ll have to pay a substantial surcharge if there are no other lodgers during your stay.

If you’re traveling in a group, both resorts also offer houseboats.

Most Royal Belum tours follow the standard itinerary mentioned above, though there are several other rafflesia viewpoints, orang asli villages, salt licks and waterfalls.

These tours only take you to the fringes of the park, so if you’re looking for a more intrepid experience in the forest, try Belum Adventure Camp.

There are also fishing and bird-watching tours, as well as excursions outside Royal Belum in the Temengor Forest Reserve, which doesn’t require a permit.

Belum.com.my is a useful one-stop shop to book car transfers, houseboat stays and tours. Alternatively, try Asian Trails (contact Abu Fadzil at +60 19 393 0592 or [email protected]).

You can also check out what the touts offer at Banding Island’s public jetty.

If you want to plan a trip yourself, you can look up the register of boat operators and tour guides on the Perak State Park Corporation’s website.

Emily Ding is a freelance writer and photographer based in Malaysia.