Like the legendary curse of the mummy, ancient Egypt refuses to stay buried in the past. Every so often it comes back to life – in the 1920s with the discovery of King Tut’s tomb; in the 1970s with the global tour of those golden masks; and most recently with a flurry of astonishing discoveries using 21st-century archaeological techniques.

During the past year alone, Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities has announced discoveries including:

? A 4,400-year-old tomb at the Saqqara archaeological site

? Eight mummies from the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BC) – many of them encased in vividly painted coffins – at the Dahshur necropolis near Giza

? A stone sphinx at Kom Ombo, a riverside temple near Aswan dedicated to the crocodile god Sobek

? A surprisingly sophisticated 4,500-year-old ramp network at the Hatnub alabaster quarry in the Eastern Desert that may help solve ongoing questions about how the ancient Egyptians built the pyramids

? A 3,200-year-old hunk of sheep and goat cheese in a tomb at Saqqara, the first-ever evidence that cheese was part of the ancient Egyptian diet

? A well-preserved female mummy – and around 1,000 ushabti statues representing servants who would attend to the deceased in the afterlife — in a 17th Dynasty tomb near the Valley of Kings

Egypt is also in the midst of a museum construction boom, including new collections scheduled to open soon in the Red Sea resort towns of Sharm el-Sheikh and Hurghada that will give beachgoers a chance to browse ancient Egyptian artifacts without venturing to Cairo or Luxor.

Meanwhile, the long-awaited Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) is nearly finished. After a series of delays, the world’s largest museum dedicated to a single civilization is now slated for a grand opening in mid-2020.

Located near the Giza pyramids on the outskirts of the Egyptian capital, the museum will showcase more than 100,000 objects, including every single item found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, many of them never before on public display.

Pharaonic aficionados may have to wait a few more years for the GEM to open, but there’s still plenty of ancient Egypt that’s ready to view right now when you travel here:

Egyptian Museum

Until the new museum opens and all of the artifacts are transferred to Giza, the old Egyptian Museum overlooking Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo offers the planet’s best ensemble of ancient Egyptian artifacts.

Like that warehouse at the end of “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” the museum is a jumble of relics large and small scattered through a colossal structure built by the British in 1902. The Mummy Room and Tut’s Treasure are must sees. All of the artifacts in the collection are gradually being moved to the new Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza.

Pyramids at Giza

Big, bad and bold, there’s nothing on Earth quite like the three pyramids of Giza. Straddling the divide between the Sahara desert and Cairo’s urban sprawl, the structures were erected four and a half thousand years ago as the tombs for three Old Kingdom pharaohs. The largest one – the Great Pyramid of Khufu – comprises 2.3 million stone blocks with a combined mass of 5.75 million tons (16 times more than the Empire State Building).

You can no longer climb the pyramids, but visitors can enter the burial chambers, ogle the solar boats uncovered beside the structures, or pose on a camel with the pyramids rising in the background.

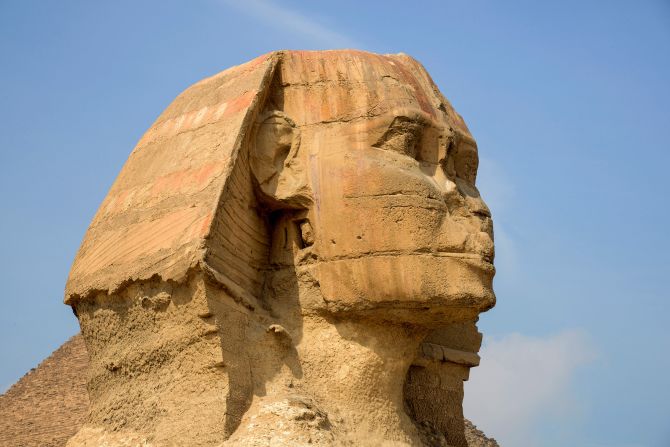

The Great Sphinx

Crouching at the foot of the pyramids, the Sphinx is the oldest known monumental sculpture in all of Egypt, carved into the limestone bedrock of the Giza plateau in the 26th century BC.

Instantly emblematic of the ancient civilization that created it, the 240-foot-long sculpture blends a lion’s body and a human head into a fearsome creature that later Arab invaders dubbed The Terrifying One.

Step Pyramid of Saqqara

Located about 20 miles south of Cairo in the Nile Valley, the mud-brick structure was the prototype that sparked the ancient Egyptian pyramid boom.

Pharaoh Djoser commissioned a flat, rectangular mastaba-style tomb in the manner of previous rulers. But the architect decided to experiment by placing six increasingly smaller mastabas atop one another until the tomb was around 200 feet tall – what is now considered the world’s first true pyramid.

Alexandria

The celebrated lighthouse – one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World – tumbled into the harbor centuries ago. But Egypt’s second largest city boasts many other wonders from Greek and Roman times including the eerie Catacombs of Kom el Shaqafa, the ruins of Kom el Dikka, and Pompey’s Pillar with its twin sphinx.

Resurrecting the celebrated library that was destroyed during the 3rd century AD, the ultra-modern Bibliotheca Alexandrina contains four museums including one dedicated to ancient Egypt.

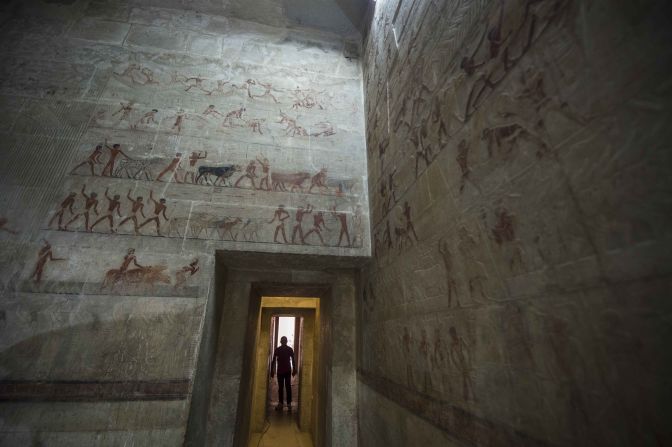

Valley of the Kings

Following their mummification, Egypt’s New Dynasty pharaohs were buried in secret tombs in a bone-dry desert canyon beyond the western bank of the Nile. Sixty-three tombs have thus far been discovered there, the most recent in 2005. And while tomb robbers pillaged most of their underground treasures long ago, the walls themselves are priceless pieces of art, decorated with brightly painted scenes of the gods and ancient life, as well as hieroglyphics.

More than a dozen tombs are open to the public on a rotating basis, including the lasting resting places of Tutankhamun, Ramses IV and Tutmosis III.

Temple of Karnak

Egypt’s largest ancient temple rises on the opposite side of the Nile from the Valley of the Kings. Erected over hundreds of years, the shrine boasts a number of stone landmarks including the Hypostyle Hall with its massive lotus columns and a long Avenue of Sphinxes.

Karnak is worth visiting twice: once by daylight to study the architectural details and again at night for the sound and light show.

Temple of Luxor

Poised along the banks of the Nile in the middle of the city that bears its name, the Temple of Luxor is a miniature version of Karnak with its own colossal statues and soaring lotus columns.

Some Egyptologists believe that it once served as the place where pharaohs were crowned. It’s best visited after dark when the temple precinct is artfully illuminated and much easier to photograph than hulking Karnak.

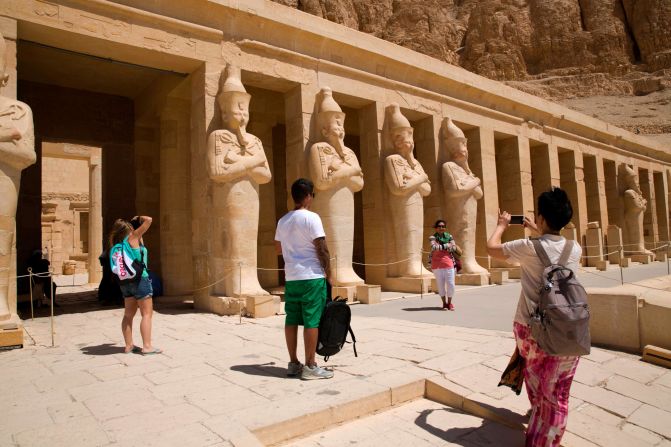

Temple of Hatshepsut

Luxor’s west bank is littered with the mortuary temples of many ancient pharaohs, but none as grand as the shrine dedicated to Queen Hatshepsut. The design is striking – totally different than anything else in Luxor – a long ramp leading to three tiers of stone columns arranged at the bottom of a towering sandstone cliff.

Like other monarchs, the queen was buried in a secret tomb in the Valley of Kings. But her mortuary temple was open to the public for those who wanted to worship Hatshepsut after death.

Abu Simbel

Lost beneath the sands for thousands of years and then saved from the rising waters of Lake Nasser by a monumental moving project in the 1960s, these temples once marked the southern boundary of ancient Egypt.

Hewn from a solid rock wall, four massive statues of Ramses the Great flank the entrance to an inner sanctum flanked by more colossal statues. Twice each year (February 22 and October 22), the rising sun shines all the way down the central aisle, illuminating statues of Ramses and three gods.

Philae Temple Complex

Abu Simbel wasn’t the only ancient shrine saved from the Aswan dams. A superb temple compound on Philae Island was also rescued from the lake waters.

Dedicated to the fertility goddess Isis, the main temple was built in the 4th-century BC and is believed to be the last place where the ancient Egyptian religion was practiced and where the last original hieroglyphics were inscribed. The only way to reach the complex is via small boat from a landing near the Old Aswan Dam.

Siwa Oasis

Alexander the Great ventured across the Sahara Desert in 331 BC to visit an oracle that pronounced him the rightful heir to Egypt’s pharaonic crown.

The ruins of the Temple of the Oracle of Amun – which dates back to the 26th Dynasty – perches on a hilltop overlooking the palm-shaded oasis. A theory that Alexander was buried at Siwa has never been verified.

Tell el Amarna

Located around 200 miles (320 km) south of Cairo in the Nile Valley, Tell el Amarna is the Arabic term for Akhetaten – the short-lived capital of Egypt in the 14th century BC.

Founded by Akhenaten, the husband of Queen Nefertiti and the father of Tutankhamun, the city was also the base of his controversial monotheistic cult. Akhetaten was destroyed after the pharaoh’s death and lost to the desert until the 1790s when Napoleon’s corps de savants came across the ruins. Highlights of the modern archeological park are the two dozen, vividly decorated noble tombs.

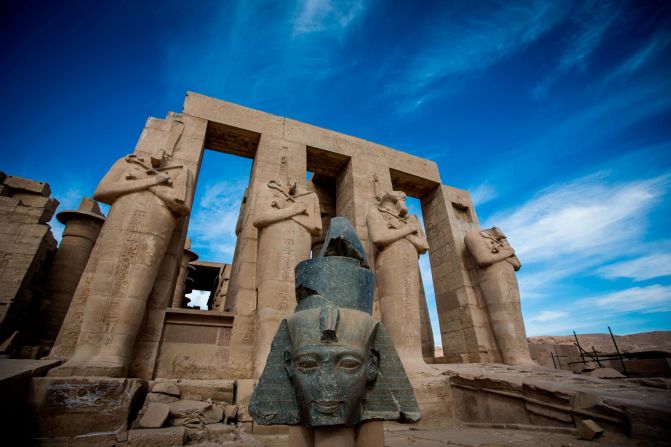

Ramesseum

Poetry fans will recognize the giant toppled head beside this 13th-century BC temple as the Ozymandias of the celebrated sonnet by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Located across the River Nile from Luxor, the immense structure is the mortuary temple of Ramses the Great, the same ruler who commissioned Abu Simbel. In addition to the toppled-over Ozymandias, the complex boasts other colossal statues of gods and the man who was probably the greatest pharaoh of ancient Egypt.

Joe Yogerst is a freelance travel, business and entertainment writer based in California.