Behind closed doors at the UK headquarters of Rolls-Royce Aerospace, machinery whirs, fans hum and blades screech as some 1,000 people go about the complex task of getting an airplane engine off the ground.

“It’s all about keeping customers happy and keeping up with the popularity of the engine we’re trying to make,” says Michael McCree, an improvements engineer on Rolls-Royce’s Trent XWB engine line.

“Sure, we’ve done the designs that are popular, we’ve done products that are popular – but can we keep the production rate going?”

The Trent XWB engine is a turbofan jet engine that powers up the Airbus A350 XWB. Chance are, you’re flown with one. You’ll find it powering airlines around the world, such as Qatar Airways, Singapore Airlines and Lufthansa.

More than 1,800 Trent XWB engines are in service or on order worldwide. And at the Rolls-Royce facility in Derby, in the East Midlands area of England, the goal is to manufacture these engines safely, quickly and to the highest standard.

McCree guides CNN Travel through the process, providing an insider look at how the XWB engine gets made and the steps required for it to take off, from manufacturing and testing, to taking to the sky.

Engineering marvel

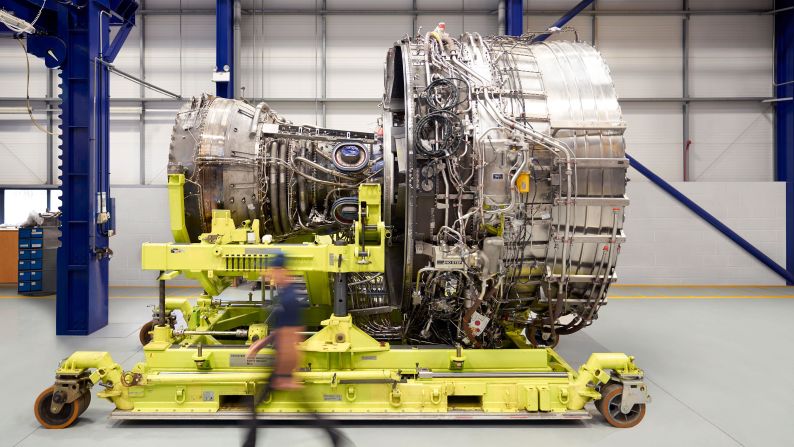

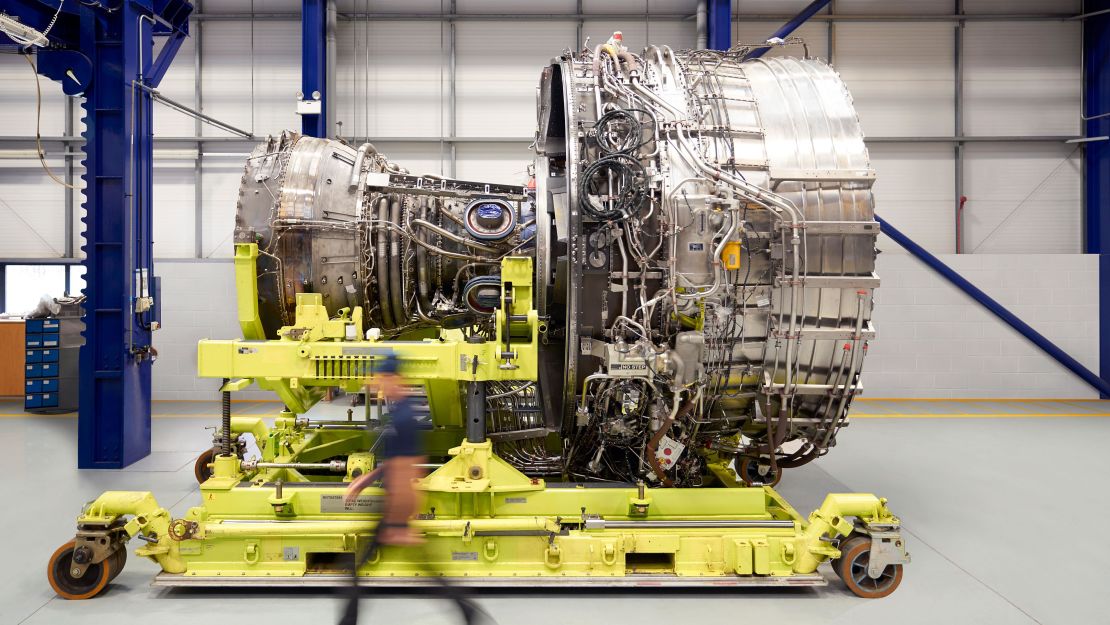

The Trent XWB engine is made up of eight key modules.

“We build six out of those eight modules in Derby,” says McCree. “We contract two to suppliers.”

The IP compressor is built by KHI in Japan, meanwhile the LP turbine is assembled by a company called ITP in Spain, then passed back to the UK.

McCree starts the tour of the Derby XWB engine production line with the fan case.

This is what goes around the outside of the engine and is usually covered with cowling, which bears the name of both the product and the airline.

“It’s there to to hold all of the wiring and pipework, as well as to contain the fan blades,” says McCree, pointing out a bare fan case with a carbon fiber top.

The fan case has a “wet” side” and a “dry” side. The wet side is where the fuel and oil go and the dry side is where the cables and electronics sit – far enough away from the liquids to avoid any issues there.

“We have three fitters per shift, working per fan case,” explains McCree.

“Each fan case is split into thirds, so one person is working on a set build area, rather than having to cross over to work around each other.”

The next step is the part of the engine you’ll see on an airplane – the big fan that spins at the front.

Weights are used to balance the fan and ensure it works to specifications.

“A bit like you would if your car wheels were a bit wobbly, you can stick some extra weights on the inside – we effectively bolt some weights on the inside to counteract any sort of minor differences in vibration – so what we need to do is build a kind of net vibration of zero across the engine, across all the parts, to make sure that the customers’ ride is as smooth as possible,” says McCree.

The experience of flyers is always at the forefront of Rolls-Royce’s mind. Ideally, you’re barely aware of the engine – except for the fact it’s getting you from point A to point B.

As CNN Travel walks past this section of the line, one Rolls-Royce employee is spinning the fan in a big box-like machine. Computer software is illustrating where he needs to place the weights.

“It’s really important that it’s as balanced and accurate as possible,” says McCree.

Any imbalance would cause major problems for the engine.

Next steps

Walking around the facility, there are people everywhere. Yes, there are machines – but it’s not as robotic as you might expect.

“It’s a really, really skilled job – rather than a big machine mind,” says McCree, who studied Mechanical Engineering at Imperial College London before he started a graduate job at Rolls-Royce.

The next step is to marry the combuster section to the intercase. The intercase is where the engine with the shaft going through the middle connects out to the gear box.

This part of the production line is part of a skillet line:

“So basically the floor moves forward while the tooling remains still, so the team will follow that engine moving forward,” says McCree.

The engine, at this point is essentially “bald,” says McCree. You need to turn the engine from a core to what’s called a dress core.

“Dress core’s when you put all your pipes that connect your hot and your cold engine, any sort of cables that run through,” says McCree.

The fan case is then brought through, situated on the floor and the engine is lifted up and dropped into the center of the fan case.

It’s now more recognizable as an airplane engine, but it’s still not ready to fly.

Testing process

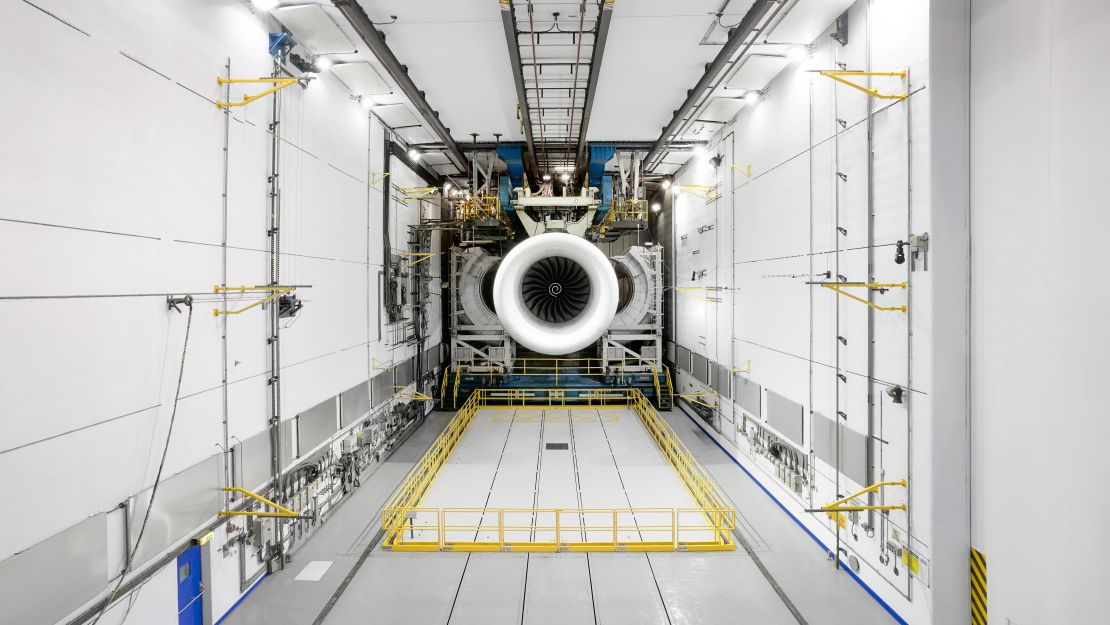

Perhaps the most impressive part of the facility is the test bed.

It’s a vast, lengthy room with a gargantuan facility holding the engine in place, ready for trial.

While the engine’s on the test bed, testers experiment with how well the engine handles start ups, emergency shutdowns and even run-ins with birds – dead birds as well as gelatine models are thrown into the engine to recreate a bird strike.

Thrust is also recorded, you don’t want any imbalance as that would impact how the engine runs.

The engine is also tested for cabin odor issues via a so-called sniff test.

“We make sure there’s no smell coming from the engine that could go into the cabin,” says McCree.

So what happens if oil is suspected to be leaking?

Cameras are taken into the engine and changes can be made.

The length of the testing process at Rolls-Royce varies. New products will be thoroughly examined for several days, but established engines that are already in production can be confirmed flight-ready after a shorter period of testing.

Getting the airplane off the ground

When the engine is ready for operation it’s taken apart, split in half via a hydraulic machine and transported on the back of a truck, usually to Airbus’ HQ in Toulouse in France, ready to form part of an Airbus A350 XWB.

Each engine will go through roughly 3,000 flight cycles before it needs to be serviced, transporting thousands and thousands of passengers to their destination.

So how does the airplane engine get the aircraft off the ground?

“There’s four words to describe our jet engine which are suck, squeeze, bang, blow,” says McCree.

First up: suck – the fan on the front sucks in air and 80% of that air goes through past the engine and blows air out the back – that provides the majority of the thrust, that pushes your engine forward.

The fan turns via the core, which takes the other 20% of the air and compresses it down, so it gets smaller and smaller.

“That’s the squeeze part,” says McCree.

The air mixes with the fuel and then that’s set alight via ignition – that, of course, is the bang.

The final part? Well, as the compressor gets smaller, the turbine gets bigger, extracting more energy. The air is going through and spins at each stage.

“A bit like when you’re at the beach, and you’ve got the little kind of windmills that you blow,” says McCree. “It’s effectively loads and loads of stages that are extracting more and more and more of that energy.”

Civilian feedback

Rolls-Royce is keen to stress that the Trent XWB is fuel-efficient, as well as reliable. It’s apparently got a 15% fuel consumption advantage compared to the original Trent engine.

Plus, it’s quiet – even if each of the 68 high pressure turbine blades generates 800 horsepower at take off – the equivalent of a Formula 1 car.

There are 68 blades and in total at take off they produce 50,000hp.

It’s the general surreptitious nature of the airplane engine that means airline passengers, unless they’re self-confessed AV Geeks, probably don’t think much about the mechanics of what’s getting them off the ground.

“A lot of people get on the plane, they don’t know who makes the engine – often they don’t care,” Caroline Day, head of marketing, strategy and future programs at Rolls-Royce, tells CNN Travel.

Still, she says, growing awareness of the climate crisis is changing this mindset, somewhat.

In this ever-connected era, the engine manufacturer can’t just consider the aircraft manufacturers and the airline – the average flyer is getting involved in the conversation too.

And many travelers are becoming more concerned about their carbon footprint and holding carriers to account.

“I think through social media, now we’re getting a lot more engagement with the public, which is great,” says Day.

“We’re very conscious of this pressure of climate change. I like to think we can demonstrate that we are absolutely doing our bit,” she adds. “We are trying to burn less fuel and reduce emissions.”