Editor’s Note: This feature is part of CNN Style’s series Hyphenated, which explores the complex issue of identity among minorities in the United States.

Yelaine Rodriguez is used to people making assumptions about her identity and what she does.

A first-generation Afro Dominican American born and raised in the Bronx, the now-30-year-old artist remembers the backhanded compliments she would receive as a teen and young adult – comments like, “Oh, you don’t seem like you’re from the Bronx,” weren’t uncommon.

Even after Rodriguez started teaching at her alma mater, Parsons School of Design, some parents of her students seemed surprised by her background: “Your parents must be so proud of you,” she can recall being told.

“That was really frustrating to me because it shows that they didn’t really care enough to educate themselves about people that were living above 86th street,” said Rodriguez, referring to the subway stop where she said most White people at the time got off the train as it approached the Bronx.

“I never hid that I was from the Bronx, that I was Afro Dominican,” she continued. “I always loved putting people in their place by telling them, ‘Yeah, I am from there, why are you surprised about that?’”

Today, Rodriguez uses her artwork to challenge other problematic assumptions relating to Afro Latinx and Caribbean culture.

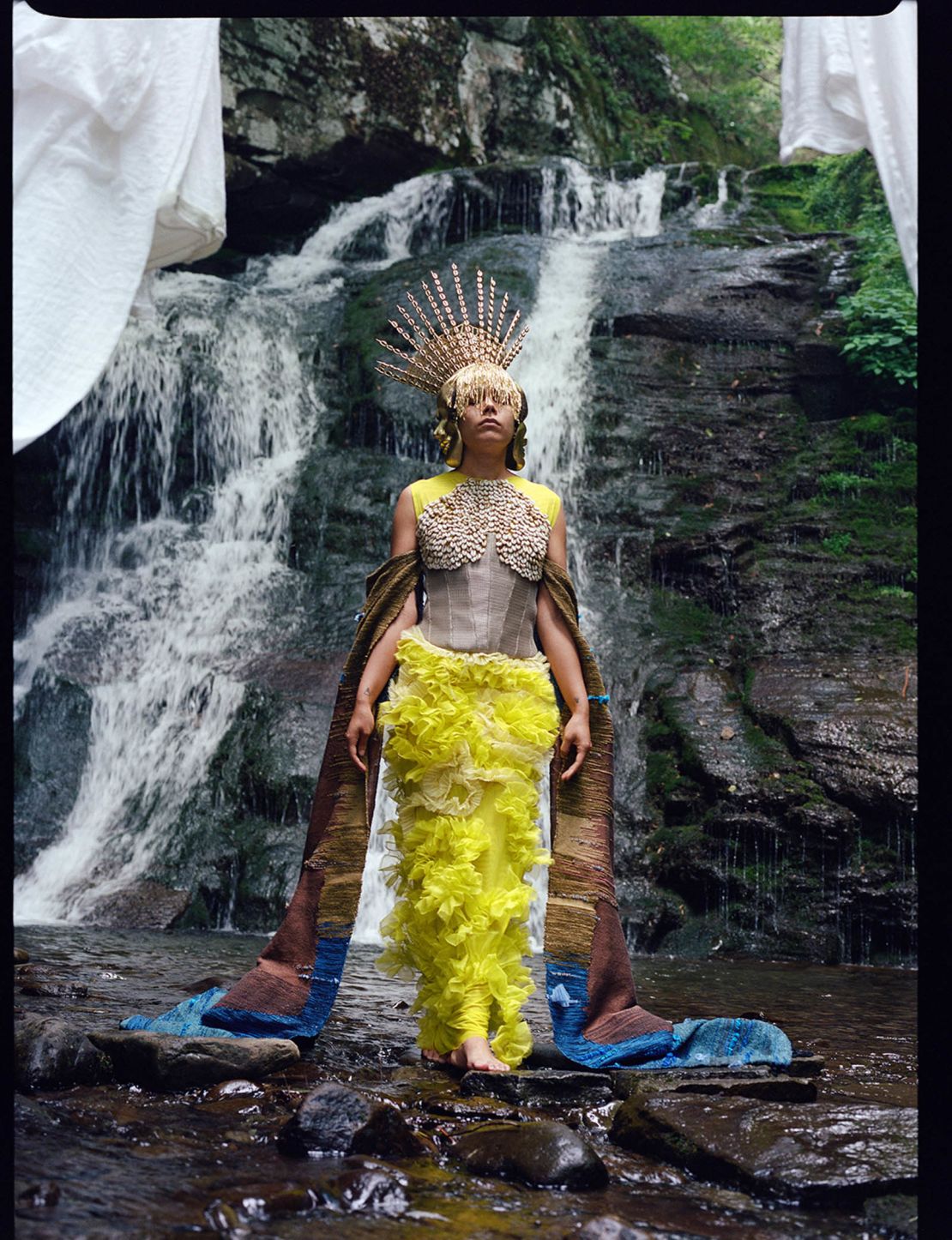

With a background in fashion design, she crafts what she calls wearable art, placing her bold designs, often modeled by friends and other artists and creatives of color, into visual narratives depicting deities and stories in African-derived or African diaspora religions like Santeria and Vodou.

Acknowledging the stereotypes

In America and Europe, popular culture has often mischaracterized religions such as Vodou as evil, revenge-seeking practices, using tropes that include inserting pins into dolls and zombies. In George A. Romeros’ 1968 classic, “Night of the Living Dead,” for example, the flesh-eating monsters may have roots Vodou folklore, but their gruesome Hollywood depiction is a far cry from their Haitian origins.

But Rodriguez also believes negative stigmas were attached to these religions much earlier on. “For me the reason (the religions) have these negative things attached to them is because they come from Black culture,” she said. “If you actually do the research to understand why they were condemned, you’d know it was a plot by the colonizer to make these Afro-derived traditions or cultures into something that they’re not.”

Ultimately, Rodriguez believes the misconceptions stem from a lack of understanding and education.

Syncretic religions, or religions derived from multiple influences, are historically rich in and complex in their traditions. Voudou blends the beliefs of the Yoruba people of West Africa with Roman Catholicism and was born in Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) as a result of slave trading during the 16th and 17th centuries. Santeria is a similar blend of Catholicism and Yoruba traditions, but its origins trace back to Cuba.

That embrace of Christian imagery was a calculated move on the slaves’ part, Rodriguez said, in order to preserve their heritage.

Rodriguez is inspired by an “endurance to thrive” as an Afro Latinx person navigating both the Caribbean and American Black experiences. Syncretic religions “are forms of resistance” themselves, she said.

“They weren’t able to practice it at times, it was illegal, it became so stigmatized.”

Rodriguez’s multimedia art practice aims to challenge misconceptions about these religions and show their true beauty, strength and continued connection to Black and African diaspora cultures today.

Her project “Oshun Orisha of Fertility: Help Us Birth Generations of Revolutionary Womxn” – currently part of the “Estamos Bien: La Trienal 20/21” exhibit at El Museo del Barrio in New York City – gets at this link by drawing a metaphorical line between Oshun, the fertility goddess of the Yoruba people, and American Black women who fought for women’s right to vote in the 20th century.

The work features Rodriguez’s close friend and fellow Afro Dominican artist Patricia Encarnacion wearing a gold headpiece that serves as both a crown and partial mask; a vibrant, yellow dress; and rich brown cape dripping with blue threads. According to Rodriguez, the cape is representative of the African slaves brought to the Americas – blue for the waters they traveled across, brown for their scars.

Her use of the fertility goddess alludes to birthing revolutionary women, like those who fought for the passage of the 19th amendment.

In an artist statement published on her website and on Vogue.com she wrote, “We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors that paved the way and pass the baton forward. So that we may continue to carry the message onward, therefore it may never be lost.”

In addition to honoring her ancestors, Rodriguez loves that syncretism is a tradition that unites Black people of different nationalities.

“Wherever Black people are, that practice a form of Afro syncretic religion, they’re all very similar to each other even though they may have their differences,” she said. She pointed to Santeria’s existence in Puerto Rico, Cuba and the Dominican Republic and compared it to the Candomblé religion in Brazil and Winti in Suriname.

“It’s a really beautiful way of connecting with people across the world and to not think that we’re that separate from each other.”

“Estamos Bien: La Trienal 20/21” is at El Museo del Barrio in New York City until September 26.