There is a scene in “Eyes Wide Shut” in which Tom Cruise’s character, Bill, and a prostitute named Domino enter a New York building apartment through a red doorway.

The doorway is on screen just for seconds. It doesn’t seem to be particularly important, and yet it has become a symbol of director Stanley Kubrick’s obsession with detail.

In a 2004 essay, writer Jon Ronson described visiting Kubrick’s home and discovering a box with hundreds of photographs of doorways. “Probably just about every doorway in London,” neatly cataloged by borough, was included, with the words “hooker doorway?” handwritten at the top.

“Eyes Wide Shut” is set in New York, but it’s filmed entirely in London, with the streets of the West Village painstakingly reconstructed at London’s Pinewood Studios and on location in the city’s East End. Kubrick had sent his nephew around town on a quest to find the perfect door for him. In the end, Kubrick decided to build his own, along with an entire city block, based off thousands of other photographs that he had also commissioned in New York.

For the same movie, which took 15 months to film, he needed a tiny news story to appear in a prop copy of the New York Post that Cruise reads in a single shot. He personally called an actual Post reporter to make sure the story looked exactly as if it was real. Then he had his assistant follow up on the project for months, through at least 100 calls, according to the reporter. He also wanted the prop to use the same paper as the actual Post, so he had some shipped from New York to London.

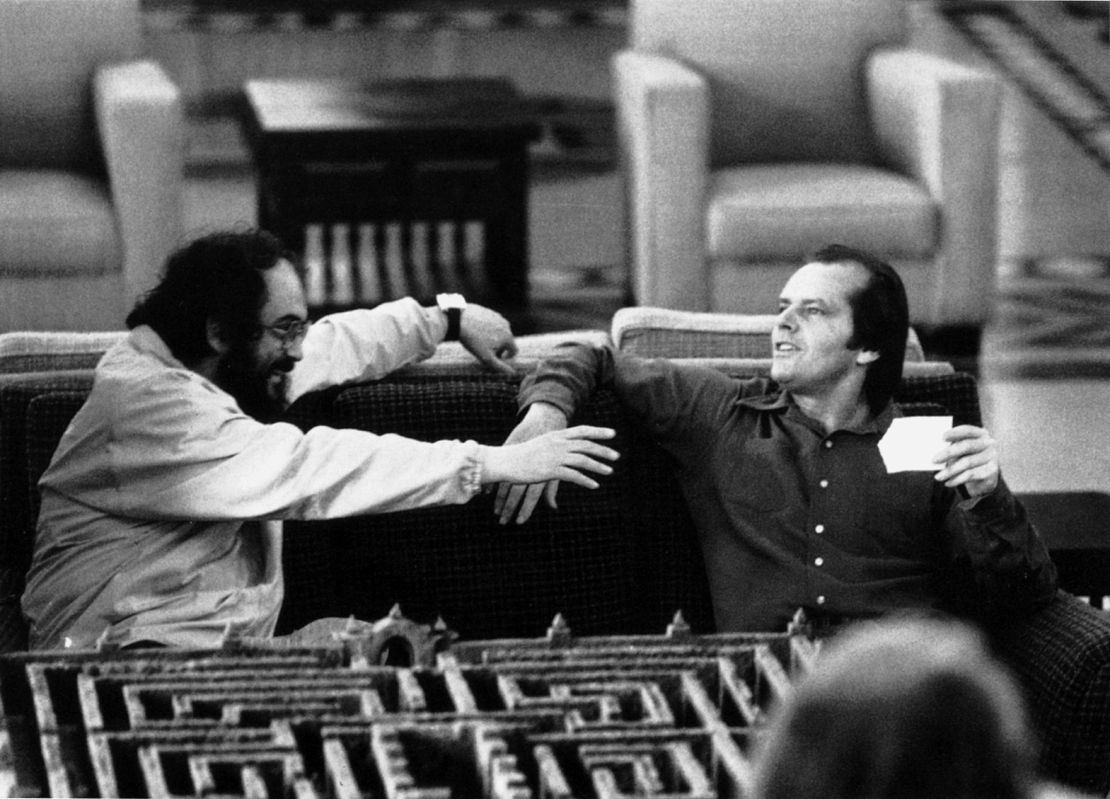

“His attention to detail and his care is what created such extraordinary films,” Deyan Sudjic, director of London’s Design Museum, said in a phone interview. “He exposed a lot more film than anybody else would have done. He spent a lot more time on projects than anybody else would have done. But that’s what makes the films so special.”

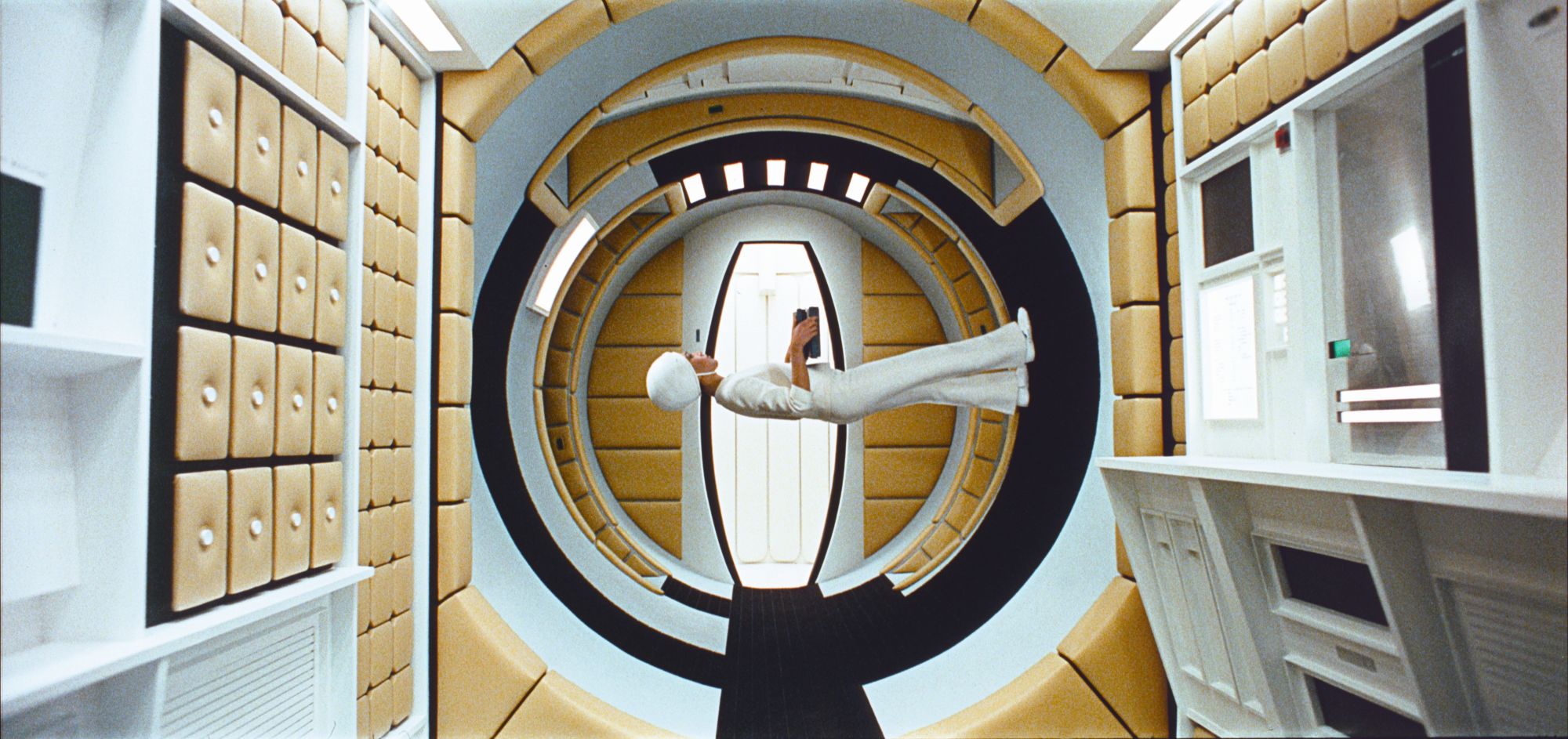

The Design Museum is hosting an exhibition that explores Kubrick’s unique relationship with the design process in filmmaking. Visitors first take a stroll down a replica of the carpet from “The Shining,” before entering rooms themed around “Barry Lyndon,” “Full Metal Jacket,” “Paths of Glory,” “Spartacus,” “Lolita,” “Eyes Wide Shut,” “Dr. Strangelove” and, of course, “2001: Space Odyssey,” including a model of the centrifuge set that was developed for the film and an encounter with rogue AI HAL.

Among the 700 objects featured are classic props such as the Durango 95, the car that actor Malcolm McDowell drove in “A Clockwork Orange,” and Private Joker’s helmet from “Full Metal Jacket.”

“This exhibition has been touring since 2004, and we had a unique opportunity to give it a fresh look, especially since London has been a home and an office to Kubrick for so many years. It’s also been 20 years since his passing,” said curator Adri?nne Groen.

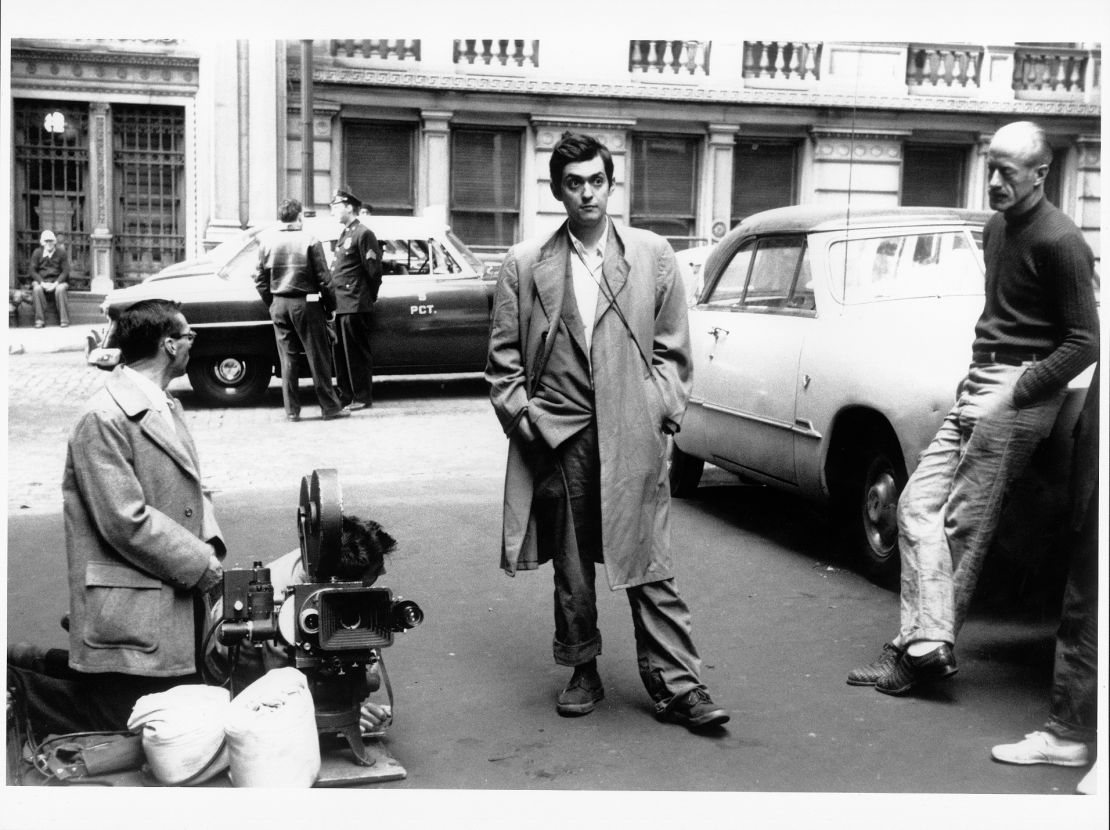

Born in the Bronx, New York, in 1928, Kubrick moved to England in 1962 to film the controversial hit “Lolita” and never returned. In 1978, he bought Childwickbury Manor, an 18-bedroom mansion in Hertfordshire, a half-hour drive from London, which became his command center and home until his death in 1999. (He is buried there next to his daughter Anya.)

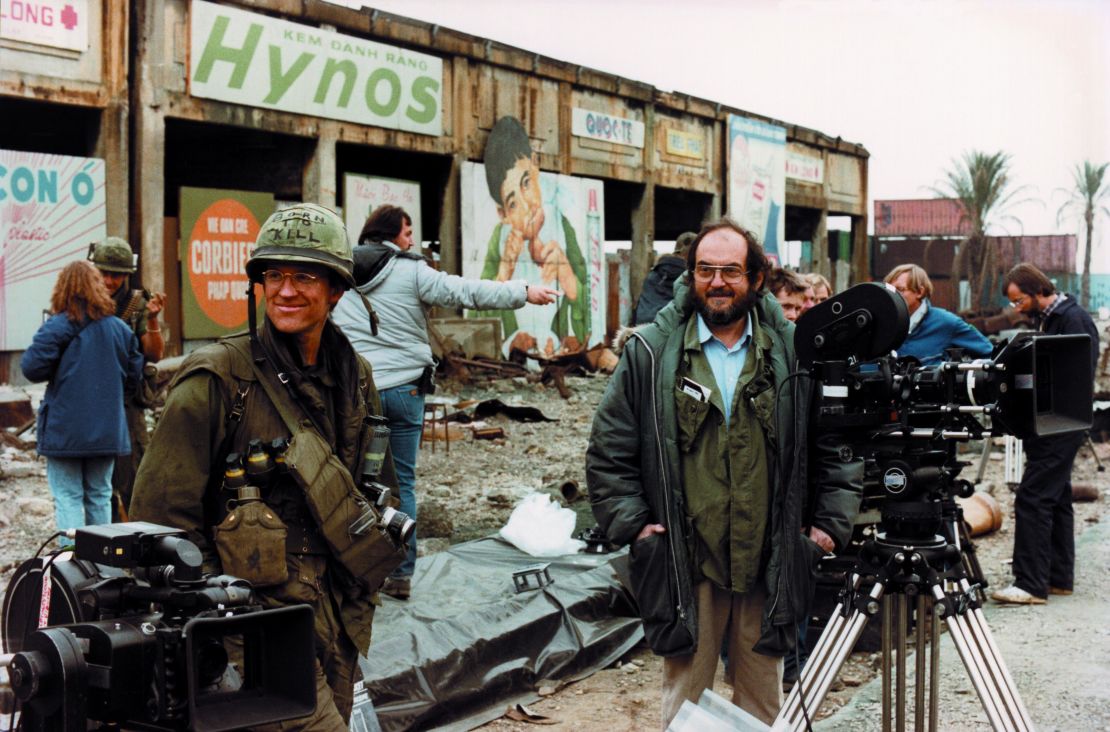

Kubrick was a private man who seldom traveled. As a result, Kubrick liked to make his films close to home. The hotel from “The Shining,” fictionally set in the Rocky Mountains, was recreated at Elstree Studios near London, just 12 miles from Kubrick’s house; and even the Vietnam scenes in “Full Metal Jacket” were filmed in east London, with the help of 200 palm trees flown in from Spain

“He created so many different worlds in London. We’ve looked at how he transformed London’s East End into Greenwich Village. We’ve looked at how London’s Beckton Gasworks were turned into the battle scenes from Hu?, Vietnam for ‘Full Metal Jacket.’ For ‘Barry Lyndon,’ he wanted art director Ken Adam to find all locations within a 40 mile radius of his house in Hertfordshire. When Adam pointed out that some of these would have to be farther away, Kubrick said ‘Right, you go and shoot them as a second unit director,’ which he did,” said Sudjic.

The collaboration with Adam reached its peak in “Dr. Strangelove” with the construction of the movie’s war room, which Steven Spielberg reportedly called the best movie set of all time.

“There’s the famous story that Reagan, when he became president, wanted to be shown where the war room was, because he assumed that it was real,” Sudjic said.

The exhibition also explores Kubrick’s collaborations with other legendary designers such as Saul Bass, who made storyboards for “Spartacus” and a series of posters for “The Shining;” Milena Canonero, who won an Oscar for the costumes in “Barry Lyndon,” and Hardy Amies, an official dressmaker for the Queen of England, who designed the costumes for “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

It’s hard to pick a standout in Kubrick’s masterpiece-laden career, but few movies have enjoyed as much unrelenting acclaim as “2001” has in the last 50 years. Today, the details of Kubrick’s vision and design can be scrutinized even more closely thanks to modern restorations of the original prints.

“Kubrick changed the way we saw science fiction films,” said Sudjic. “He wanted a sense of the near future, a believable future. It went from bug-eyed monsters to plausible spaceships.”

“Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition” is at London’s Design Museum from April 26, 2019 to Sept. 15, 2019.