With its heavy-duty concrete structure, the vaulted Chorsu Bazaar in the Uzbek capital Tashkent exudes the architectural starkness typical of Soviet Modernism. However, the blue and turquoise tiling decorating its dome looks decidedly Islamic.

The blending of the two styles is visually arresting. It’s also a far-cry from the drab, soulless designs often associated with Soviet-era architecture.

Built in 1980, the market was one of the many buildings in Central Asia developed under the Soviet regime that controlled much of the region, from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, during the second half of the 20th century.

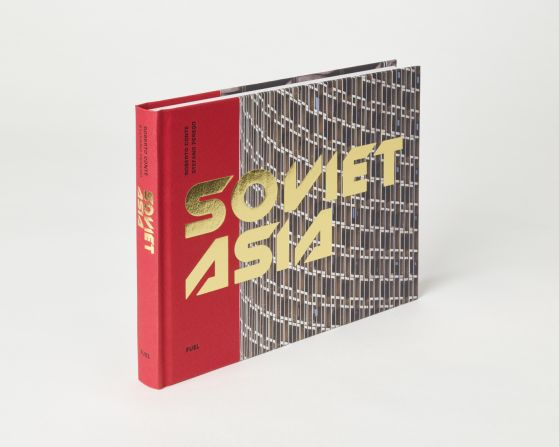

Most of these constructions display equally composite aesthetics, colors and motifs, offering a different take on the standard socialist architecture of the former eastern bloc – one that a new book, “Soviet Asia,” is setting to document.

Photos explore another side of Soviet architecture

Traveling across Central Asia’s former Soviet republics, Italian photographers Roberto Conte and Stefano Perego captured the largely unknown modernist buildings that shaped the area’s urban development between 1955 and 1991.

“We wanted to catalogue the genuinely unique way Soviet Modernism was interpreted in those countries and illustrate how local architectural canons were incorporated within the larger architectural movement,” said Perego in a phone interview.

Indeed, the structures they photographed – an array of housing complexes, museums, libraries, circuses and governmental offices – reveal Eastern elements and characteristics, such as polychromatic tiles and the prominent use of mosaics.

Often, they draw from Persian and Islamic influences, which heavily shaped the region’s history and identity in centuries past and informed much of its architecture before the assimilation into the USSR. In many buildings, straight lines are interrupted or replaced by ornate curved forms. Rather than bare, solemn facades, mesmerizing geometric patterns dominate many of the exteriors. The Chorsu Bazaar is a case in point.

Alessandro De Magistris, an architect and professor of architectural and urban history at the Polytechnic University of Milan said the buildings shed light on the depth and diversity of Soviet Modernism. “Until recently, Soviet architecture has only been looked at from a Western perspective, and deemed as a homogenous, linear phenomenon. The buildings portrayed in Soviet Asia tell a very different story,” said De Magistris, who wrote an essay for the book, in a phone interview.

“Their purpose was that of carrying out the social program of the Soviet state – their monumentality is testament to that. But the way they express such purpose is remarkably original. They were highly expressive, experimental projects.”

De Magistris explained that while standardization was the driving force for modern socialist architecture, designers often tried to include decorative adaptations and local folklore in their work.

“There are plenty of cases where individual artistic elements or currents were used. The West simply largely ignored them, particularly in geographical areas far from Europe, like Central Asia.”

In photographing the buildings, Conte and Perego made a point, when possible, to either include people, so as to give a sense of their sheer size, or the surrounding environment, to highlight how they fit within it.

“What interested us was framing each project within the cultural and urban contexts they are in today,” Perego said.

Unlike other former Soviet republics where socialist buildings have often been left to crumble, many of the structures shown in Soviet Asia are still in use, and, in a few cases, have become major landmarks. “There’s a strong cultural interest in preserving them,” Conte said. “Some conservancy groups have formed in recent years, and they are aware of their architectural significance.”

Still, due to a lingering ambivalence towards the Soviet past, some of the buildings in more peripheral districts, particularly mass-produced public housing, have been left to deteriorate. Others are threatened with demolition.

The photographers hope their book will expose the architectural realities of a less-explored side of Soviet Modernism.

“These buildings are melting pots of national traditions and USSR ideology,” said Conte. “They are lesser-known architecture projects from the period, but still very much fascinating, and majestic in their own distinctive way.”

“Soviet Asia,” published by Fuel, is out now.