A century ago, glow-in-the-dark watches were an irresistible novelty. The dials, covered in a special luminous paint, shone all the time and didn’t require charging in sunlight. It looked like magic.

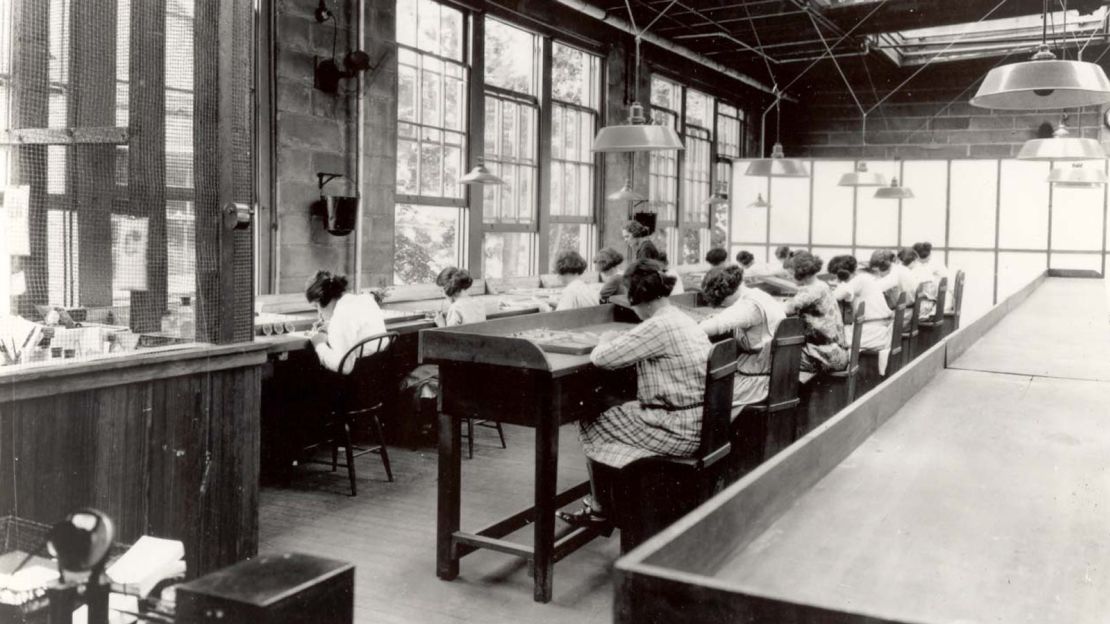

One of the first factories to produce these watches opened in New Jersey in 1916. It hired about 70 women, the first of thousands to be employed in many such factories in the United States. It was a well-paid, glamorous job.

For the delicate task of applying the paint to the tiny dials, the women were instructed to point the brushes with their lips. But the paint made the watches glow because it contained radium, a radioactive element discovered less than 20 years earlier, its properties not yet fully understood. The women were ingesting it with nearly every brushstroke.

They became known as the “Radium Girls.”

A miracle cure

Radium was discovered by Nobel laureate Marie Curie and her husband Pierre in 1898. It was quickly put to use as a cancer treatment.

“Because it was successful, it somehow became an all-powerful health tonic, taken in the same way as we take vitamins today – people were fascinated with its power,” said Kate Moore, author of “The Radium Girls,” in a phone interview.

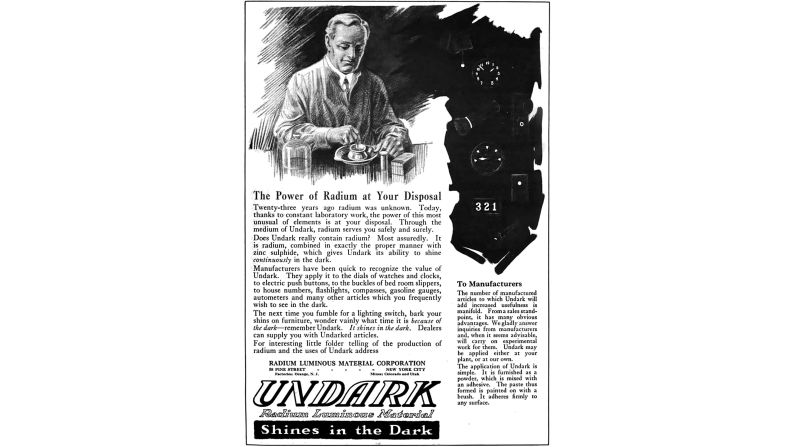

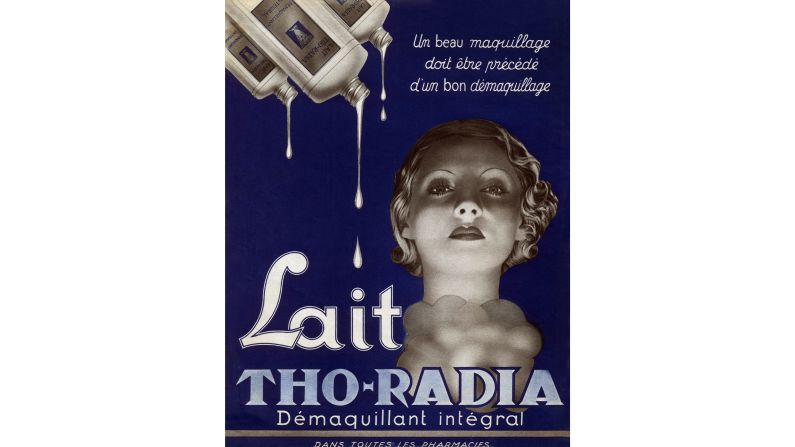

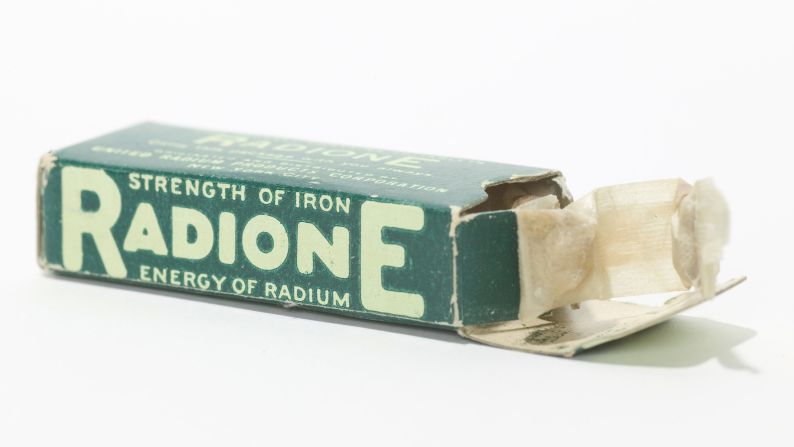

It was a proper craze. Radium became an additive in a number of everyday products, from toothpaste to cosmetics and even food and drinks. One such preparation, called Radithor, was simply distilled water with tiny amounts of the substance dissolved in it. Boldly advertised as “A Cure for the Living Dead” and “Perpetual Sunshine,” it promised to tackle various ailments from arthritis to gout.

“People knew that radioactivity released energy. And they didn’t see how adding some energy to their bodies could possibly be harmful, said Timothy Jorgensen, a radiation expert at Georgetown University and author of “Strange Glow: The Story of Radiation.”

“Radium products were used for any ailment where lack of energy was seen to be the root cause – from common fatigue to impotence,” Jorgensen said in an email.

Far from being a panacea, radium was deadly. One user, American socialite and athlete Eben Byers, became notorious for drinking a bottle of Radithor every day for years – and then dying from it in 1932. The headline of a Wall Street Journal story about his death reads, “The radium water worked fine until his jaw came off.”

A slow killer

When ingested, radium is particularly dangerous: “Chemically, it behaves very much like calcium,” said Jorgensen. “Since the body uses calcium to make bone, ingested radium is mistaken for calcium and gets incorporated into bone. So the major health risk of ingesting radium is radiation-induced bone necrosis and bone cancers. How soon they develop depends upon the dose, but at the very high doses that the Radium Girls were exposed to, just a few years.”

The luminous paint, which worked by converting the radiation into light through a fluorescent chemical, was one of the most successful radium-based products. By putting the brushes in their mouths, the Radium Girls were especially at risk – so why did they do it? “Because it was the easiest way to get a fine point on the brush, to paint on numbers as small as a single millimeter in width,” said Moore.

But the girls didn’t embrace this technique blindly. “The first thing they asked was (whether) the paint was harmful, but the managers said it was safe, which was the obvious answer for a manager of a company whose very existence depended on radium paint.”

Not all that glitters

When the luminous watches grew fashionable in the early 1920s, the world was already becoming aware of the risks of radioactivity. But radiation poisoning isn’t immediate, so years went by before any of the workers developed symptoms.

“It’s mind-boggling to think about what was known,” said Moore. “We knew from the turn of the century that radium was dangerous and large amounts of it could destroy human tissue. But one of the tricky things with it is that it does give this illusion of good health, because it stimulates the red blood cells, although obviously in the long term you’re poisoning yourself.”

The Radium Girls actually believed they were getting healthier by working with the new wonder drug – the most expensive substance in the world at the time, costing the equivalent of $2.2 million per gram in today’s money. Adding to the allure of the job, the girls were listed as ‘artists’ in their town directories. Since it was all so attractive, they even encouraged their sisters and friends to join them.

One sinister side effect was that the shimmering radioactive dust would fill the air when the paint was mixed, ending up on the women’s hair and clothes.” And the girls at the time obviously loved it and talked about wearing their good dresses to the plant, so that when they’d go out in speakeasies later they would be the ones shimmering and shining.”

Radium jaw

In the early 1920s, some of the Radium Girls started developing symptoms like fatigue and toothaches. The first death occurred in 1922, when 22-year-old Mollie Maggia died after reportedly enduring a year of pain. Although her death certificate erroneously stated that she died of syphilis, she was actually suffering from a condition called “radium jaw.” Her entire lower jawbone had become so brittle that her doctor removed it by simply lifting it out. “The radium was destroying the bone and literally drilling holes in the women’s jaws while they were still alive,” said Moore.

Yet it would take another two years before the company that owned the factory, the United States Radium Corporation, took any action at all, through an independent investigation commissioned mostly to investigate the declining business rather than the health of the workers.

In 1925 Grace Fryer, one of the workers from the original New Jersey plant, decided to sue, but she would spend two years searching for a lawyer willing to help her. She finally filed her case in 1927 along with four fellow workers, and made front-page news around the world.

The case, settled in the women’s favor in 1928, became a milestone of occupational hazard law. By this time, the dangers of radium were in full view, the lip-pointing technique was discontinued and the workers were being given protective gear. More women sued, and the radium companies appealed several times, but in 1939 the Supreme Court rejected the last appeal.

The survivors received compensation, and death certificates would start reporting the correct cause of death. The year before, the Food and Drug Administration banned the deceptive packaging of radium-based products. Radium paint itself was eventually phased out and has not been used in watches since 1968.

An enduring legacy

It’s hard to calculate how many women suffered health problems due to the ingestion of radium, but the certainly number in the thousands, according to Moore. Some of the effects would only be felt much later in life through various forms of cancer. With a half-life of 1,600 years, once the radium was inside the women’s bodies, it was there for good.

The legacy of the Radium Girls lives on through the ripples that their deaths created in labor law and our scientific understanding of the effects of radioactivity. “In the 1950s, during the Cold War, many agreed voluntarily to be studied by scientists, even with intrusive examinations because they had been exposed for prolonged periods of time,” said Moore.

“Almost everything we know about radiation inside the human body, we owe to them,” she said.