An art collective has come up with a novel way of paying off three people’s medical debt: turning their hospital bills into huge paintings and selling them to collectors for thousands of dollars.

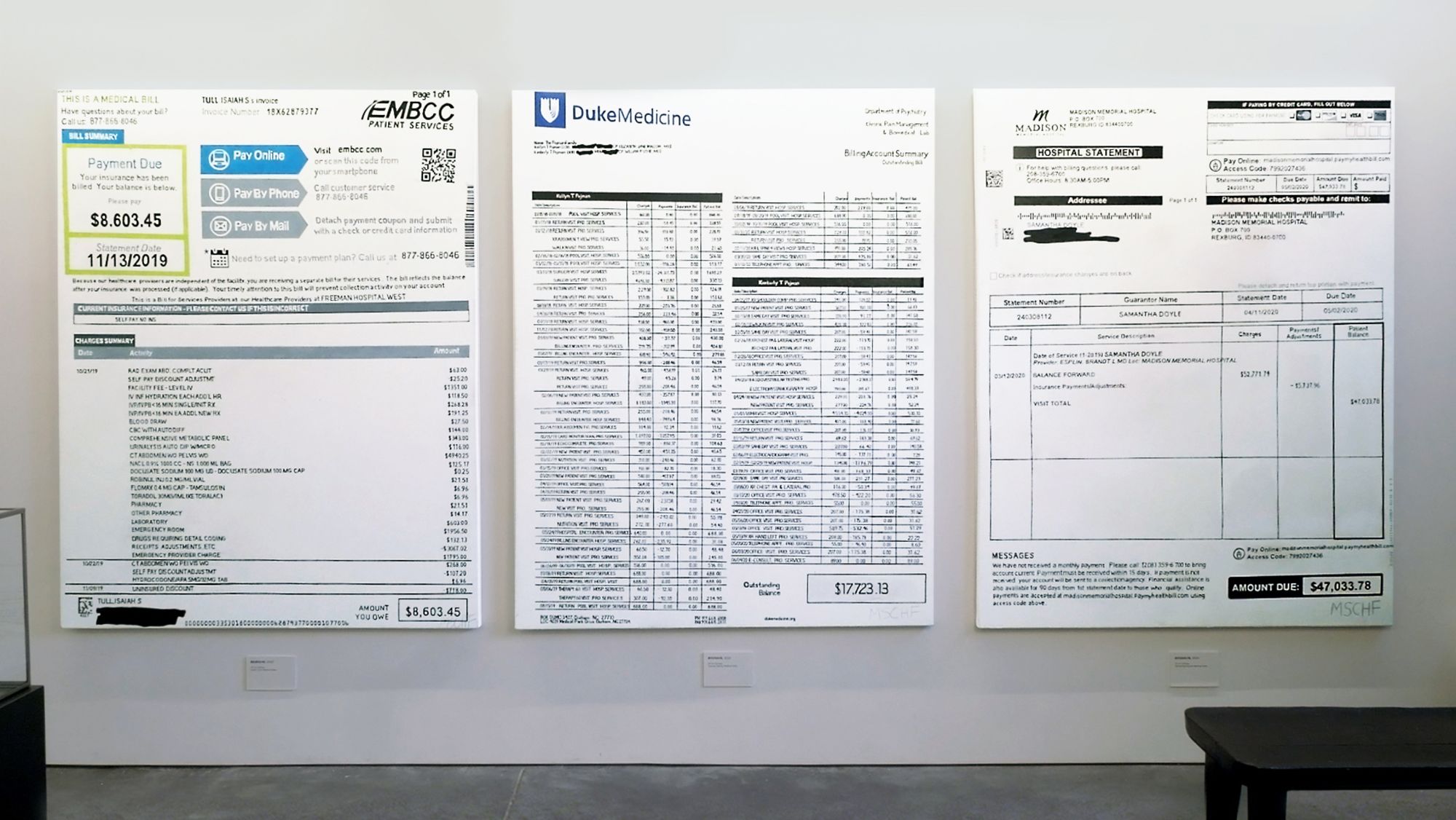

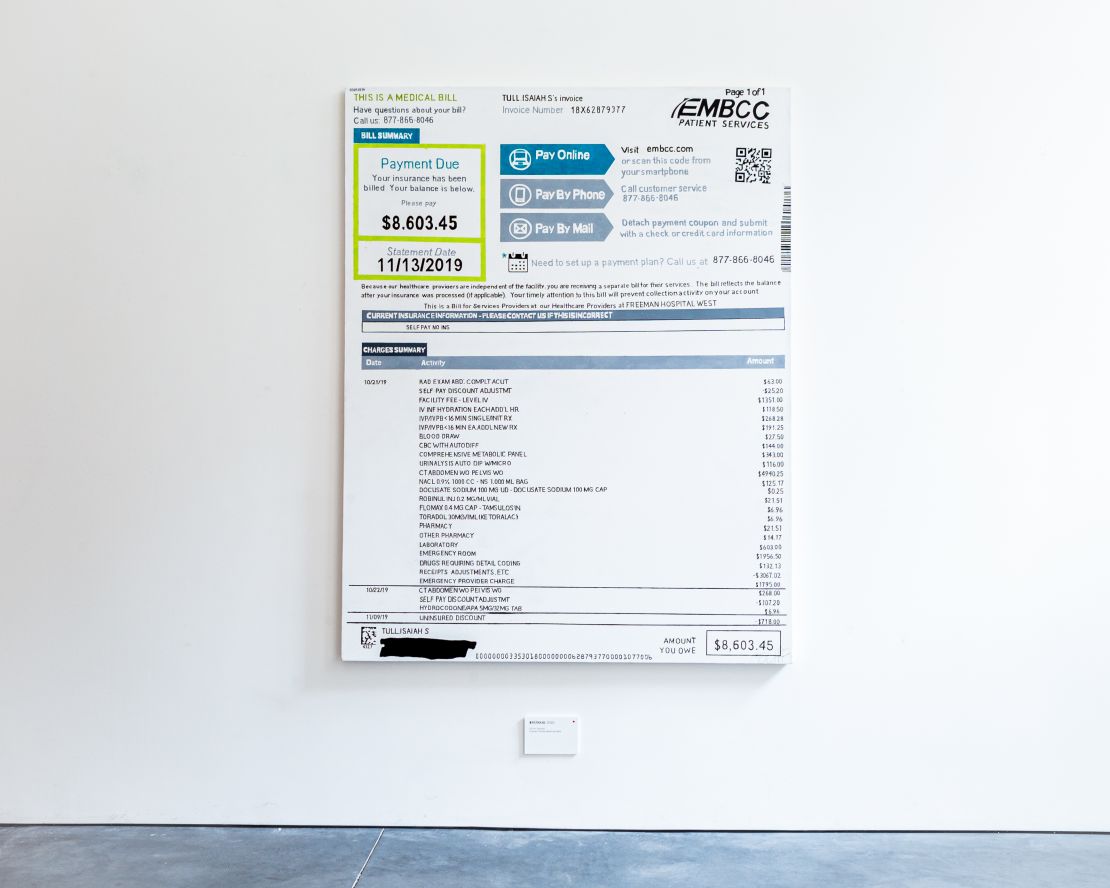

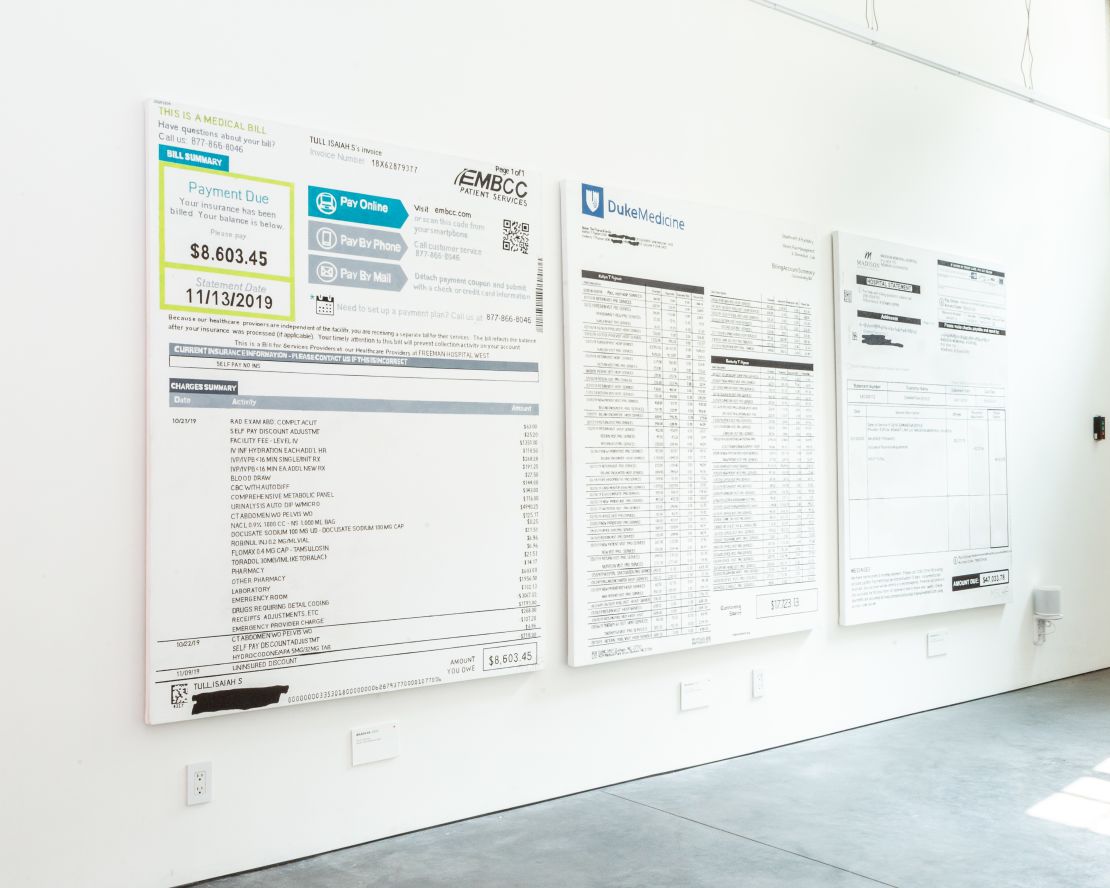

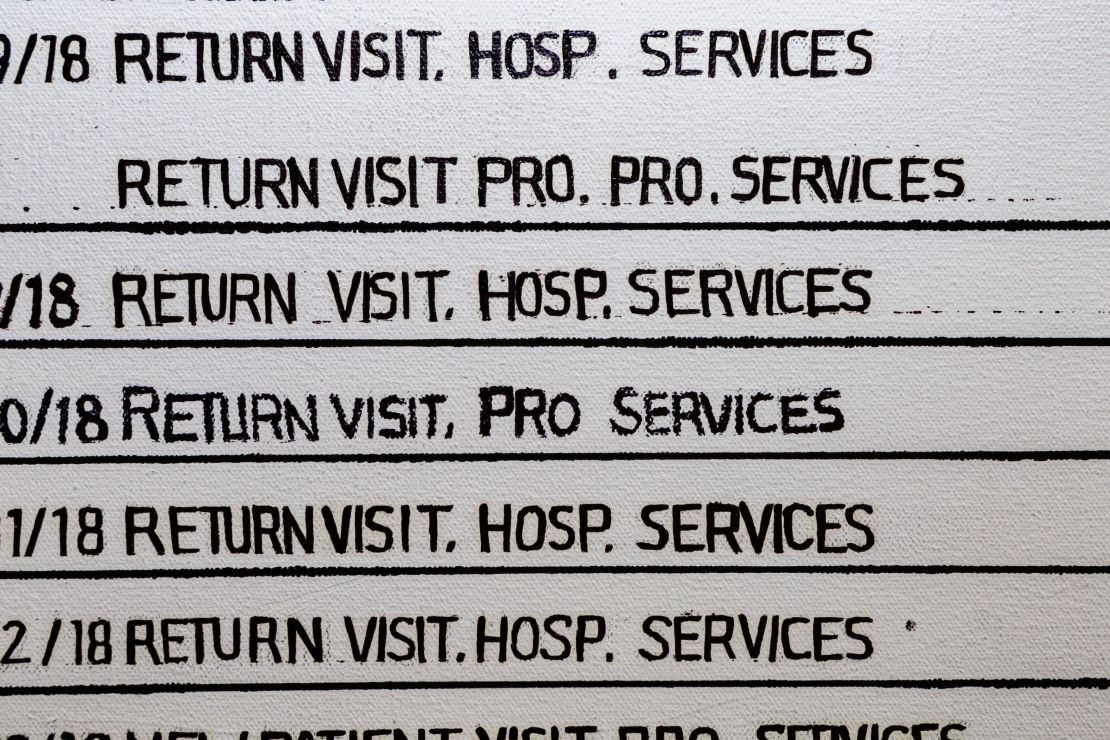

New York-based MSCHF, which is known for its irreverent art projects, identified Americans with sizable medical debt, including one with a bill for over $47,000. The group then hand-painted the invoices on 6-foot-tall canvases and sold them on the art market for precisely the amount owed.

Beyond settling these individuals’ debts with the money generated, the artists aim to make a wider commentary about the US health care system. Over 137 million people in the United States reported medical financial hardship, a 2019 study found.

“We think that the American health care system has reached such a point of runaway absurdity that an off-the-wall solution is the only fitting tactic to address it,” said the group’s head of strategy and growth, Daniel Greenberg, via email, adding that the project is “a conceptual artwork, not a reliable strategy for debt alleviation.”

“We have a culture that practically lionizes the begging-for-life paradigm of GoFundMe, or forces people to rely on Twitter clout and connections to pay. It’s terrible. In this scenario, where the only viable option to pay a medical bill is desperate workarounds, we start looking for increasingly more niche strategies.”

On the market

The project, dubbed “Medical Bill Art,” began with MSCHF placing an ad in its eponymous magazine earlier this year. About 100 people responded to the ad with information about their circumstances, according to Greenberg.

“It felt like being punched in the stomach to read our emails,” he said, adding: “Given MSCHF’s audience is young, it was especially gut-wrenching to hear from high-school and college students with tens of thousands of dollars of medical debt.”

After checking that respondents had verifiable documents, as well as ensuring that medical treatment “resulted from either injury or accident and not violence or negligence,” Greenberg said, the collective then chose three individuals at random. The large oil-on-canvas replicas of their medical bills were then sold to a New York gallery for a combined total of $73,360.36.

The gallery, Otis, is now selling “shares” in the paintings through its own investment platform. Using a model known as fractionalized ownership, whereby a number of different people take joint ownership of an artwork, collectors can now buy a portion of the paintings online for as little as $20 per share. While Otis is selling the works for the same amount they were purchased for, Greenberg suggested that they may now appreciate in value, saying that MSCHF expects the price “to increase in the secondary market.”

Although the coronavirus pandemic has prevented the group from exhibiting the paintings in New York as hoped, the artworks have been made available via a virtual gallery.

Art world commentary

Recently, MSCHF has made headlines with a number of its so-called “drops” – a series of tongue-in-cheek art projects unveiled once every two weeks. Last year, the collective sold a laptop installed with some of the world’s most dangerous computer viruses for over $1.3 million. In April, the group cut a $30,000 print by artist Damien Hirst into pieces before selling the individual parts for a huge profit.

As with previous projects, the collective is also using “Medical Bill Art” to hold up a mirror to the big-spending art world.

“One of (the) things that sticks out about contemporary made-for-gallery paintings is how great a discrepancy there can appear to be between a monochrome canvas in a Chelsea gallery and its $30,000 price tag,” Greenberg explained. “When you are making paintings specifically engineered to sell through the gallery ecosystem, you are very consciously attempting to imbue a (often visually generic) flat surface with value.

“What we find so interesting is that this can basically describe the act of printing a medical bill as well – except that value goes hard in the (opposite) direction. Our task is to equate these two things, and by doing so nullify them.”

While the group is protecting the identity of the three recipients, Greenberg said they have reported “happiness … and also a sense of disbelief that this actually worked, given how outlandish it must have sounded at the outset.”