The 20th century gave rise to one of the most enduring symbols of admiration and derision: The celebrity.

Our technology may have advanced, but the desire for images and proximity to celebrities has changed little since the early days of cinema. We expect a certain balance of the genuine and the curated in the stars – particularly the women – we elevate in the public eye and imagination.

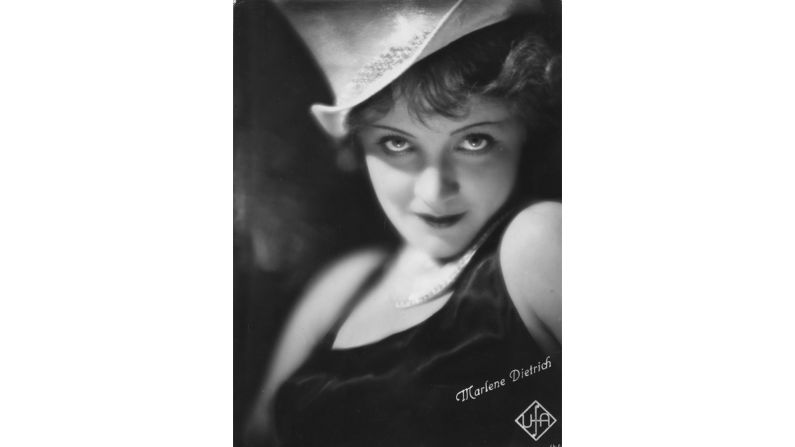

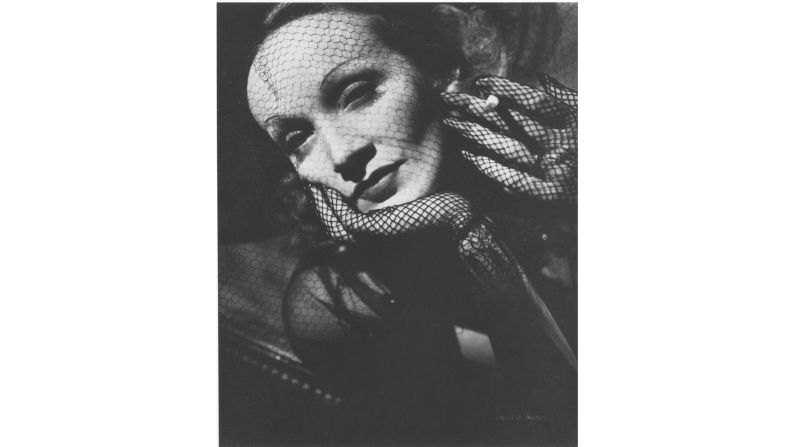

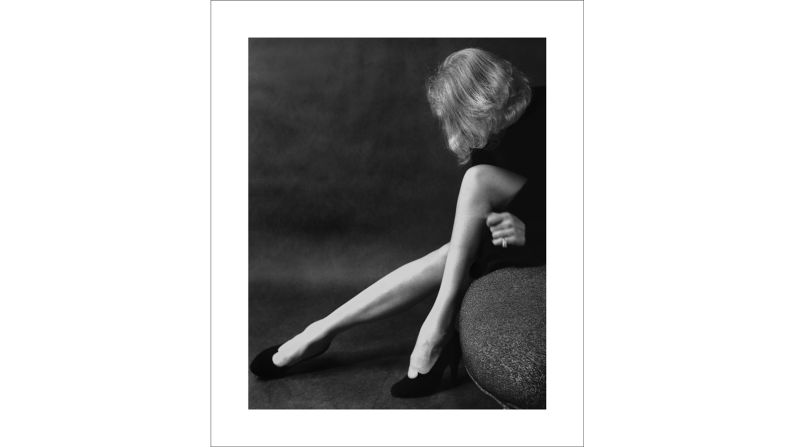

Among the earliest screen stars, few walked that line as expertly as Marlene Dietrich. The star of 1930s classics like “Shanghai Express” and “The Blue Angel,” the bisexual German actress cultivated a mysterious, commanding and sensual image of herself, all while pushing the limits of femininity and restraint, defying the norms of fashion and sexuality, and all the while resisting the threat of the Third Reich.

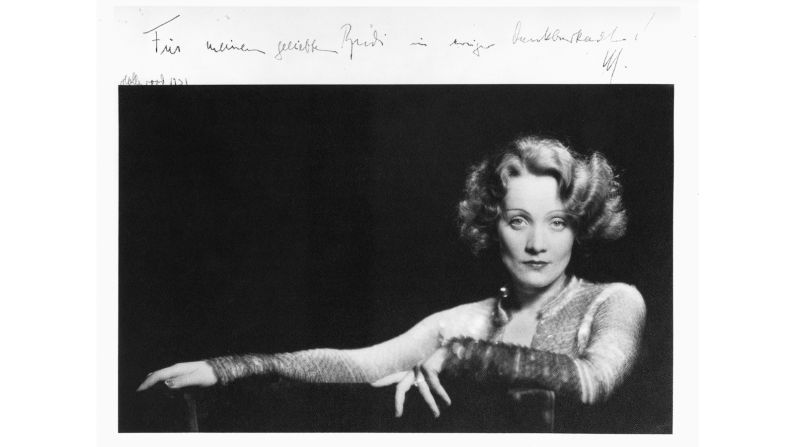

Twenty-five years after her death, her life and image are being celebrated in a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington.

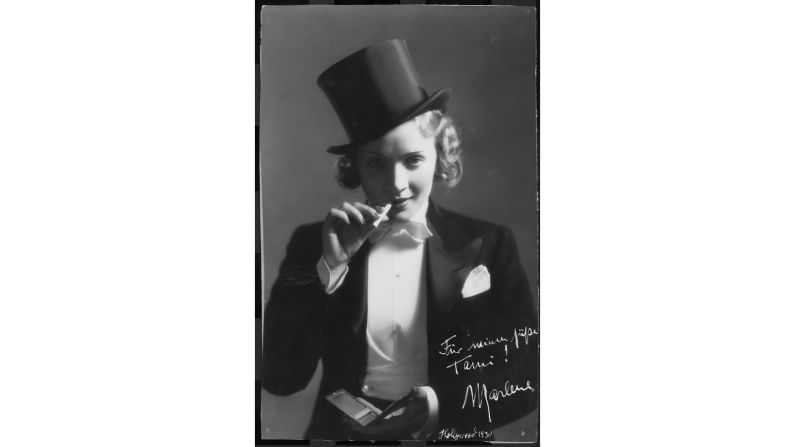

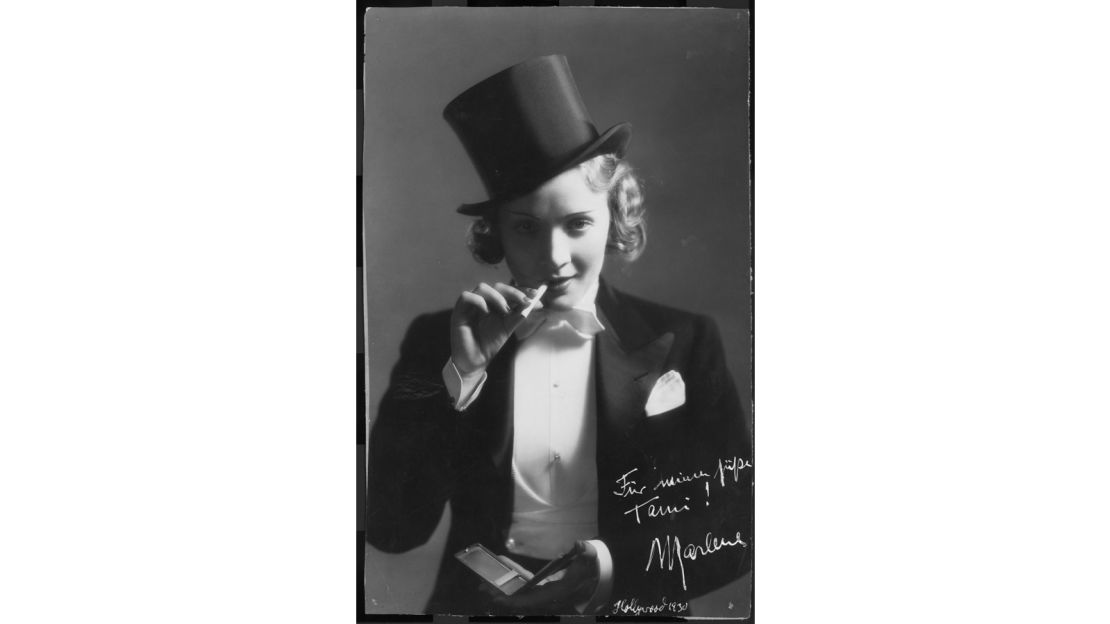

“Marlene Dietrich: Dressed for the Image” showcases the breadth and specificity of the Dietrich look through home videos, articles, photos and film clips. In tweed or top hat, she is powerful and magnetic. And that impression is real, if one that she reserved for the public.

Dressed for a scandal

Born in 1901 and raised in Berlin, Dietrich made her American debut in 1930’s “Morocco,” the Academy Award-nominated film about a cabaret singer who falls in love with a Legionnaire. In one scene, she dons a tuxedo and top hat, a cigarette hanging casually from her hand, as she sings and, at one point, kisses another women.

“It doesn’t seem like a big deal now, but in the 1930s it was big deal,” curator Kate Lemay said of Dietrich’s tuxedo. Although there were other women who wore men’s clothing at the time, Dietrich reached an audience that was unprecedented.

Dietrich’s story is one that juxtaposes tact and tenacity, as one of the stories central the exhibition shows. In 1933, Dietrich was traveling across the Atlantic on a steamer bound for Paris, wearing a white pantsuit. When the Paris chief of police got word, he announced that if she wore trousers in Paris, she would be arrested. (Until 2013, it was technically illegal for women to wear trousers.)

Dietrich doubled down. For her arrival in Paris, after docking at Cherbourg, she she chose to wear a suit, men’s coat, beret and sunglasses.

“She walked off the train, grabs the chief of police by his arm, and walks him off the platform,” said Lemay.

“The lesson of all this is that Dietrich forged an image, and then stood by it,” continued Lemay. And stand by it she did, even later in life. When she was unable to maintain the public image, she had established, she withdrew from public life.

“She understood what she had created, and she didn’t want to have that iconic image disturbed.”

Refusing the Nazis

But Dietrich was more than a dynamic image. Her public persona was largely crafted in service to her activism and, particularly in Europe, her antifascist political efforts remain an enduring part of her legacy.

Coming of age under Germany’s Weimar Republic, Dietrich valued individualism and tolerance, two values that she saw eroding quickly as Adolf Hitler rose to power in the 1930s.

“She saw the rise of the Third Reich in her home country and could not stand it. She was so upset about the betrayal she felt the Third Reich was doing to her homeland,” said Lemay.

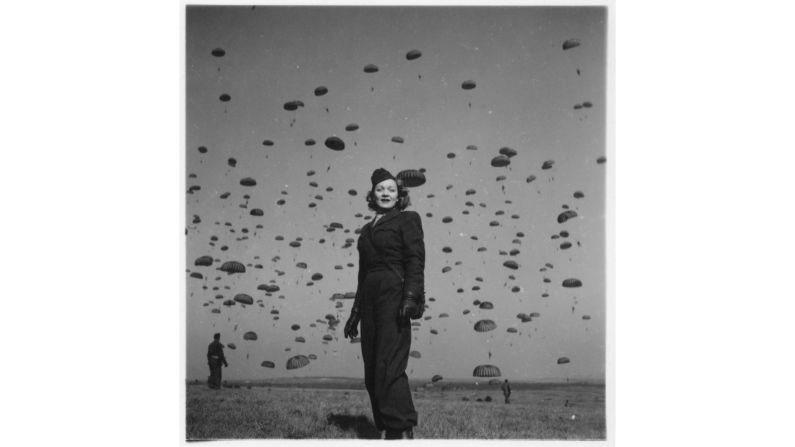

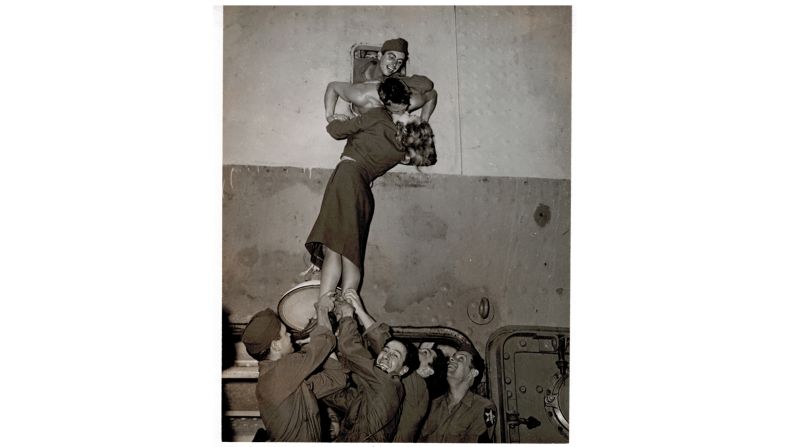

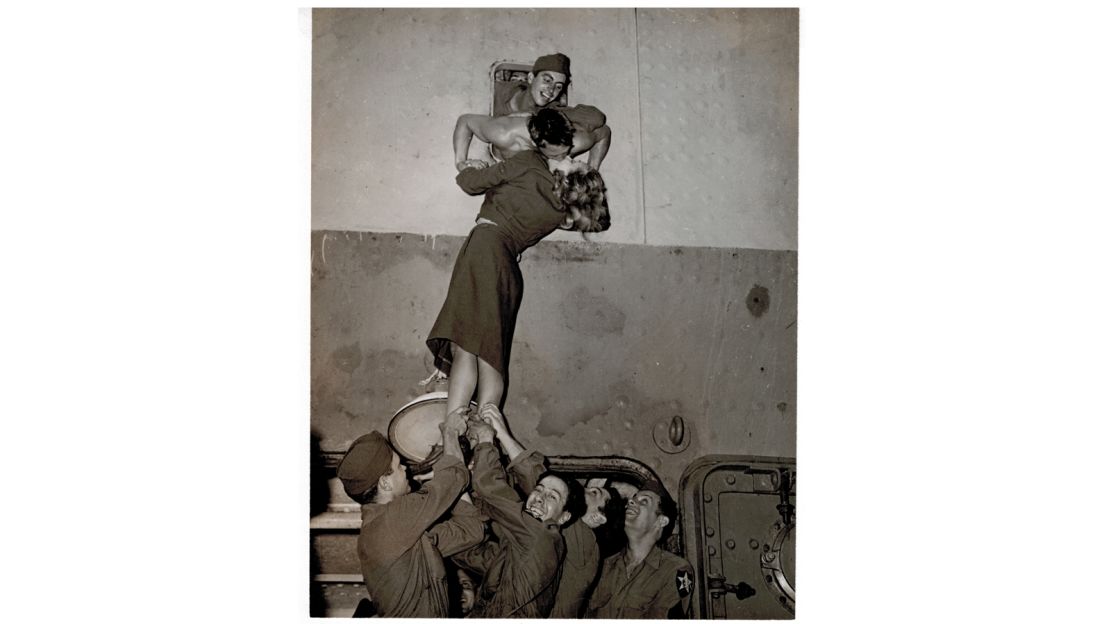

When Hitler’s government asked her to star in propaganda films in 1937, Dietrich, who had been living in the US since 1930, refused. Two years later, she renounced her German citizenship to become an American. During World War II, she was indefatigable in her efforts to sell war bonds, recorded anti-Nazi German albums for the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor to the modern CIA) and was a frequent performer near the front lines of Europe, raising morale among the soldiers, whom she called “her boys.”

Her grandson Peter Riva, remembers her friends, like comedian Danny Thomas, who performed with her, joked that “she was always trying to get us killed” by getting so close to the front.

“We’re at a moment today in which Americans particularly are asked to examine our values, and what is it that we stand for,” said Lemay, pointing to Dietrich’s personal drive to do what she saw as right above all else as one of the reasons she’s such a resonant figure today. “We aren’t isolated in history.”

Dietrich’s relationship with her home city of Berlin was troubled after the war. She was met with both standing ovations and bilingual “Marlene Go Home” placards during her first – and last – post-war trip to Germany in 1960. It wasn’t until 2002 – 10 years after her death – that she was made an honorary citizen of the city where she was born.

Since her burial in Berlin in 1992, she has remained a lightning rod in the city, as evidenced by the vandalism that has taken place at her grave. But her grandson sees this less as an attack than an acknowledgment of her continued importance:

“She’s still fighting,” he said.

“Marlene Dietrich: Dressed for the Image” is on at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington until April 15, 2018.