Story highlights

Performance artist Marina Abramovi? will teach select visitors to a pier in Sydney her "Method"

She credits it with opening forgotten parts of the psyche

“Even if I say I’m not afraid of dying, that’s not true,” says Marina Abramovi?. “Every time the plane is trembling I start writing testament.”

After 45 years of performances that have often directly confronted death, it’s the one fear Abramovi? can’t transcend. “It’s still, ‘Can I have a little bit longer?’ It’s very human.”

The artist arrives shivering from the venue where she’ll be conducting Marina Abramovi?: In Residence, in Walsh Bay’s last undeveloped wharf on the iconic Sydney Harbour. Here, the greatest threat she’ll be facing is high winter in this cavernous shipping warehouse.

“Feel this,” she says, touching my arm with icy fingers.

With 600 people allowed into the space at a time, it’s sure to warm up. Her 2010 retrospective The Artist is Present attracted record crowds of 850,000 to MoMA, confirming her status as an art world superstar.

At 69 years old, the Serbian-born artist is striking as ever, swathed in black layering, but in person she doesn’t incite tears (as she did for many spectators in New York). She’s surprisingly warm and funny, with a mystical assurance in her work’s power.

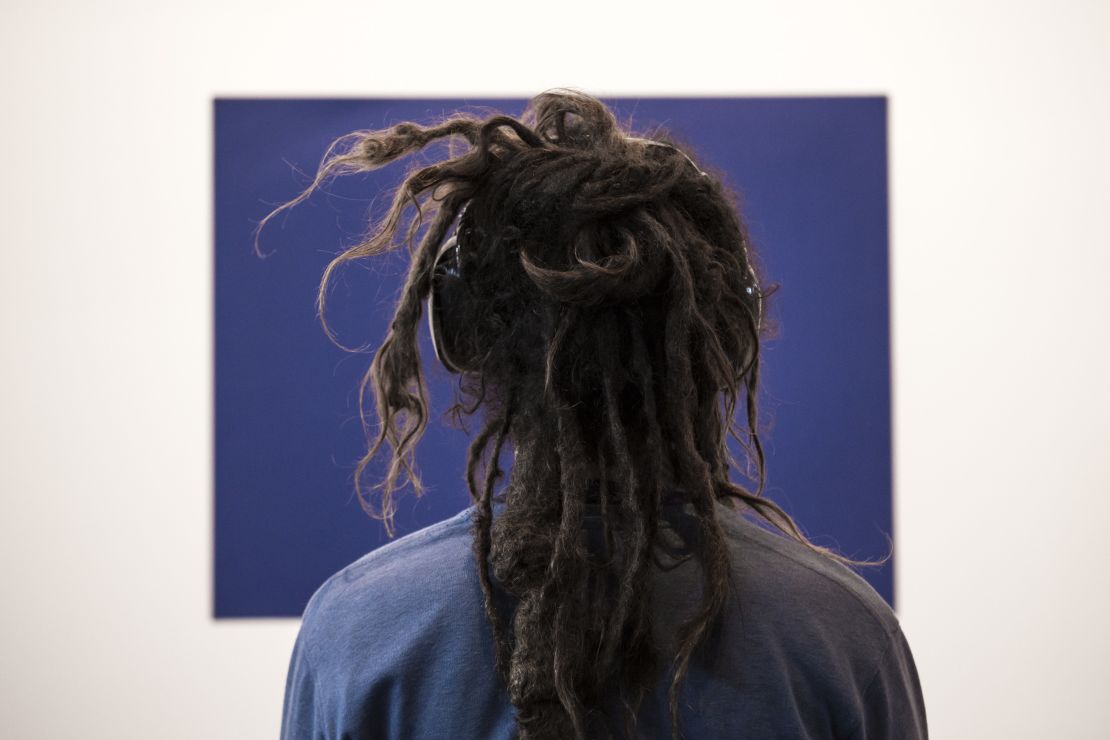

Her residency for Kaldor Public Art Projects showcases the ‘Abramovi? Method’, billed as the distillation of her life’s practice. Audiences are invited to put on noise-cancelling headphones and engage in activities that in other circumstances might be punishments: Counting rice grains, slowly walking the length of the exhibition space, standing on an elevated platform, and staring contests.

She describes the project as a “brain spa,” designed to focus and clear the mind. “The important thing is that it’s for everybody, it’s not just for the art public,” she explains. “They can be teacher, farmer, politician or housewife, so any of these people can use some of this experience in their own life.”

12 Australian artists including performers, dancers and theater-makers will be mentored in the method before creating new works upstairs.

These techniques will soon be taught at the Abramovi? Institute in Hudson, New York (where Abramovi? lives), dedicated to the preservation of this immaterial art form. When asked about the launch, she replies cryptically: “It’s not launching, it’s everywhere…. The institute is the world and the world is institute.”

According to Abramovi?, bringing ritual back to our fast-paced lives can open forgotten parts of our psyches. “We can learn telepathy in four years. We use telephones, but telepathy’s cheaper. There is so much extra sense of perception that our brain can develop with training that we don’t because we use gadgets and use computers and use all these other things that actually make us invalids.”

She gestures ruefully toward the smartphone and laptop I’m recording her with.

These techniques were partially developed during Abramovi?’s initial visits to Australia. In 1980, Abramovi? and her then-performance-partner Ulay spent a year with local Aborigines in Western Australia’s Little Sandy Desert.

“It changed my life. Everything is different,” she says. “These people are the most developed human beings on the planet … The government, just for their own benefit of uranium and all that other s**t, is destroying them.”

Tagged as “the godmother of performance art” – a title she denounces; she prefers “warrior” – she’s credited with bringing the once-derided art form into the mainstream. By now, you’d think Abramovi? would have overcome the question of whether performance is art at all.

Her early works, now considered canonical, saw her carve a pentagram into her stomach in Thomas’ Lips and let boa constrictors slither across her face in Dragon Heads. She famously gave audiences free reign over her body in Rhythm 0, with accoutrements including thorned roses, a knife and a loaded pistol.

The professional-gambler-cum-art-collector David Walsh, who is also hosting an exhibition of her work at Tasmania’s MONA, was quoted in the Murdoch-owned The Australian as saying, “Marina’s art makes my balls shrivel.”

“A huge compliment,” she laughs. “I never have such a statement in the front page … I’m thinking to take it home and frame it and put it in my bathroom immediately.”

But the radical minimalism of her recent practice is reinvigorating some scepticism. She became something of a godhead in her endurance performance at MoMA, where audiences camped overnight to sit before her and stare; disciples included James Franco and Jay Z. The performance element of her recent work at London’s Serpentine Gallery 512 Hours was Abramovi? simply walking around the space.

In Sydney, spectators must leave their possessions in a cloakroom for maximum engagement. The mindfulness it encourages is the core of many religions, and the basis of much contemporary psychology.

Abramovi? quickly rejects any suggestion that this is a form of therapy. “I don’t like to use the word therapy – and also, you know, I am artist actually, as I say, for 45 years, so whatever I do, I do in the context of art.”

While the artist will be present, the onus is on the audience to find meaning. “You go and count the rice yourself and tell me what you think about it. And I think that this question you have to answer with me, because it’s not for me to tell you.”

Abramovi? has sacrificed everything for work she believes can change human consciousness. In a life that has always been mediated by her art, there is no chance of Abramovi? retiring like her peers did long ago.

“I’m not planning to go to pension or stop making performance. I’ll probably die working.”