Recently, the conversation around cultural appropriation in fashion has been unavoidable. Headline-grabbing examples of questionable borrowing abound: In January, fashion house Comme des Gar?ons was lambasted for sending predominantly white models down the runway in cornrow wigs, while last October, country singer Kacey Musgraves received online backlash when she posted sexy photos of herself wearing a traditional Vietnamese ao dai dress on Instagram. And just last week, Kim Kardashian was once again accused of appropriating black women’s hairstyles by wearing braids at Paris Fashion Week.

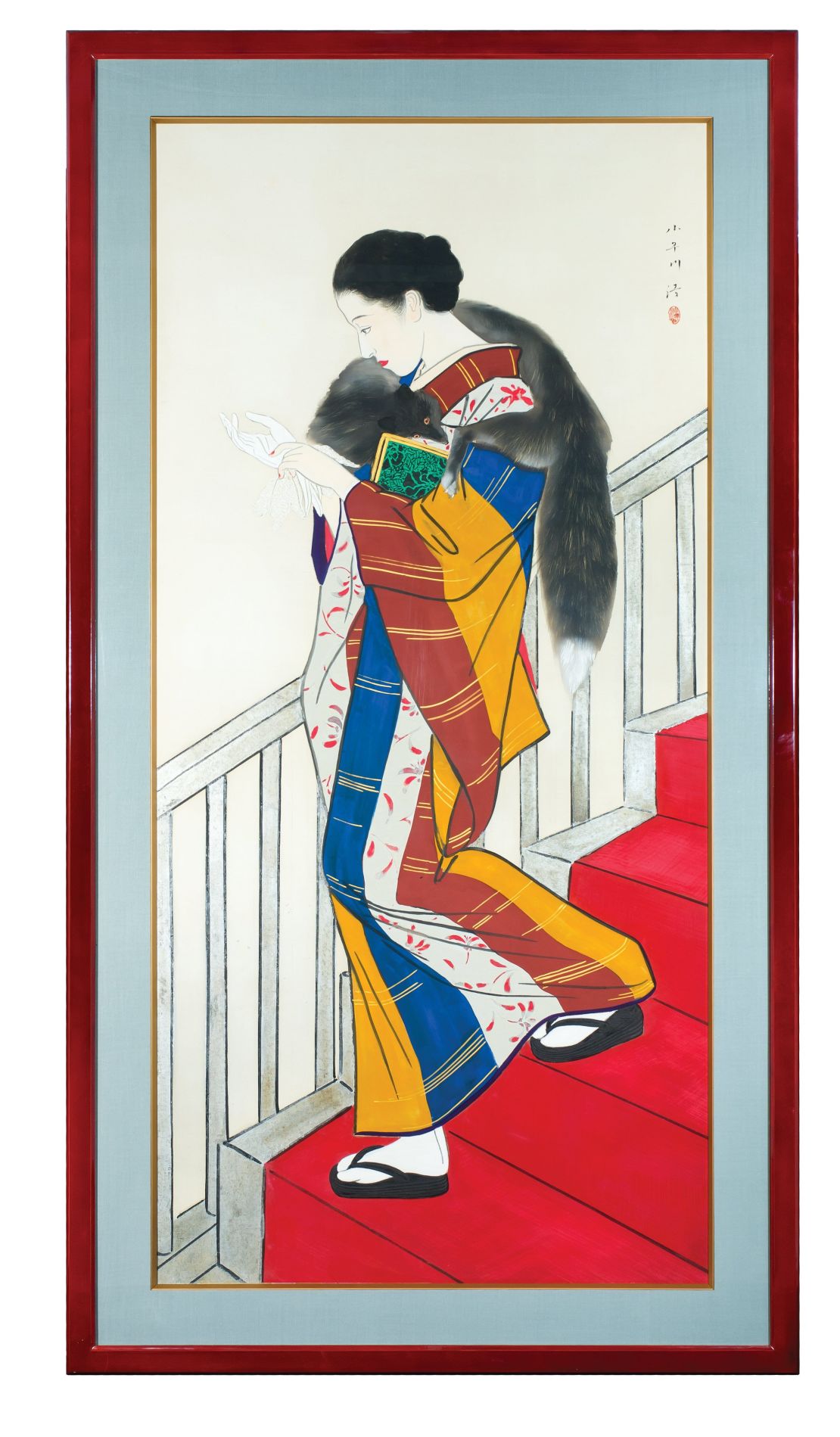

So this is, perhaps, an ideal time to consider the kimono. The T-shaped Japanese robe, which has inspired countless Western garments, complicates the conversation about what we’re allowed to adopt from other cultures and who is allowed to take offense at its suggested misuse.

In late February, the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London opened “Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk,” advertised as the first major European exhibition dedicated to the garment. Presenting 84 kimonos dating as far back as the 1660s, the show traces how the kimono became a truly global garment worn, sold, riffed on and reinvented by artisans, designers and fashion-lovers around the world.

“The kimono has this long and dynamic sartorial history,” said curator Anna Jackson. “Japan just wasn’t a passive agent in this story… It’s really a kind of dialogue.”

For centuries, the kimono has been one of Japan’s most important and recognizable cultural exports. Under Japan’s sakoku isolationist policy, the Dutch East India company enjoyed exclusive European access to Japan from the 17th to 19th century, and traders returned to Europe with kimonos. The kimono’s straight-seamed, figure-irrelevant shape and beautiful patterns caused an immediate stir. They were the antithesis of the garments that defined European fashion, which were designed to emphasize and compress different parts of the body.

“In Europe, (kimonos) were a sign of status, a sign of wealth and a sign of engagement with the outside world,” Jackson explained. “The Dutch realized there was a ready market for these kinds of robes, so they got the Japanese to make them slightly adapted. So they had more tubular sleeves, rather than a sleeve that hangs down, and much more wadding (for warmth).”

As European demand for these modified kimonos (known as night gowns, though they weren’t meant to be slept in) outpaced Japanese artisans’ production times, the Dutch turned to artisans in India and, later, European tailors to copy the garments in textiles sourced from different countries. The Dutch also brought textiles from places like India, France and Britain with them to Japan, where local designers used them to make kimonos for their wealthy patrons.

But it wasn’t until Japan was forced to open itself to the world in 1854, in line with a new act encouraging foreign trade with the West, that the kimono truly went international. As the country considered how to position itself on the world stage and establish political, cultural and economic relationships, industrious merchants saw an opportunity to sell their surplus luxury kimonos to a new audience hungry for exotic exports, and kimono manufacturers began creating and shipping new wares to Europe and America en masse.

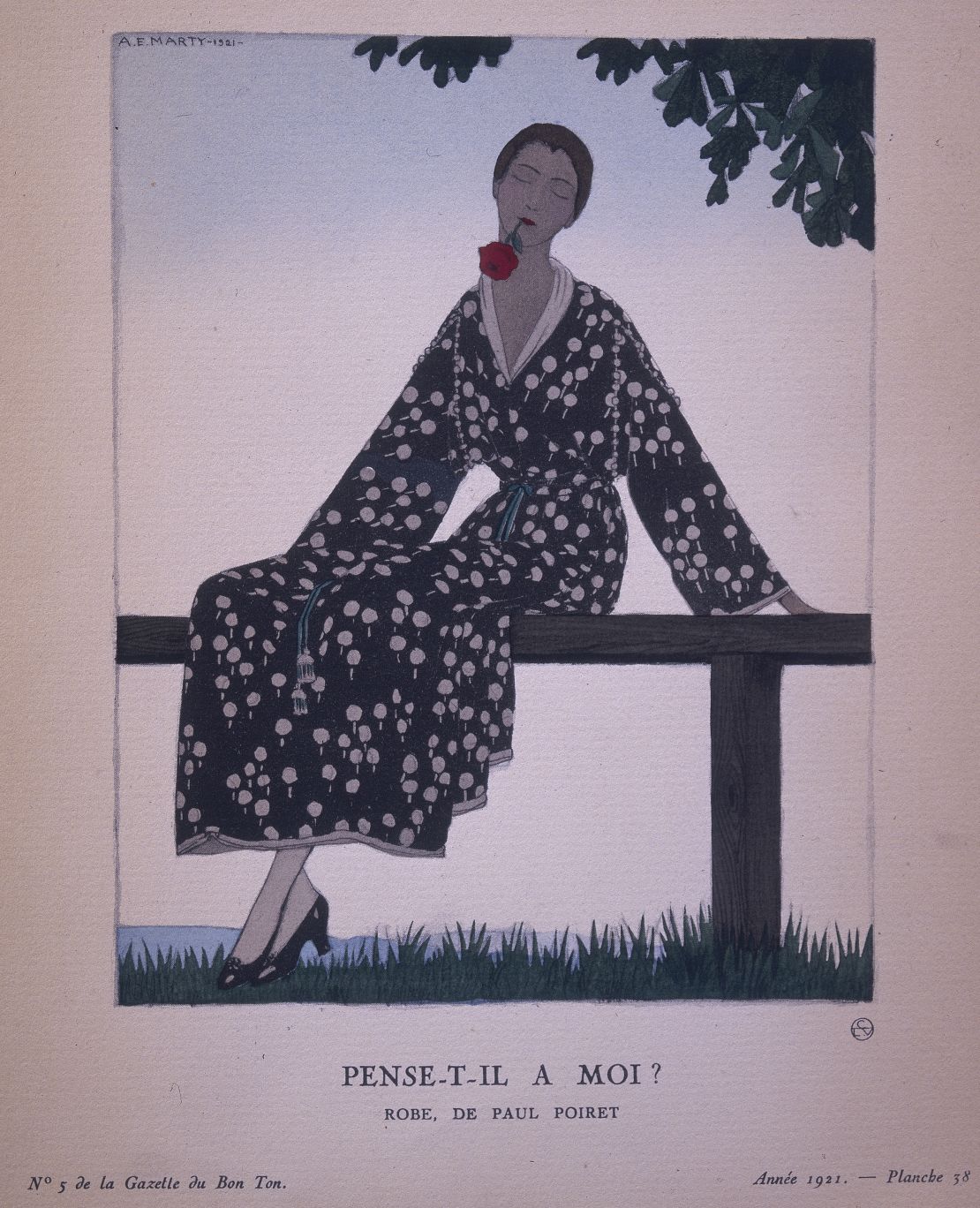

Before long, upscale department stores like Liberty in London were collaborating with Japanese designers and businesspeople to help them adapt their designs to suit their Western clientele, offering shinier satins and bigger embroidery, or adding extra panels to accommodate petticoats. French couturiers like Jeanne Lanvin, Paul Poiret and Madeleine Vionnet also began including kimono-inspired garments in their collections.

At the same time, the Japanese kimono industry – one of the country’s first to modernize – was learning from its international counterparts, adopting new technologies, techniques and aesthetics into designs for the domestic market. In the 1870s, the government of Kyoto – the capital of the kimono trade – sent students and craftsmen to Lyon, France, where they learned about the jacquard loom, flying shuttle and synthetic dyes, which presented bold new aesthetic opportunities. European influence affected domestic trends too, as Art Nouveau and Art Deco motifs, as well as skyscrapers and abstract modernist patterns, found themselves woven into kimonos.

Sarah Cheang, a researcher at London’s Royal College of Art, suggests the manufacturers’ success in both incorporating foreign practices into their domestic businesses and penetrating foreign markets is proof of an agency that non-European people are often denied in conversations about the globalization of fashion.

“You can see that the Japanese manufacturers are not just victims of colonialism… However, that kind of history is often neglected,” she said.

From the opening up of Japan in the 19th century to the period of US occupation following World War II, Cheang explained, “imperialistic outlooks made it difficult for Western commentators to see or appreciate Japanese entrepreneurship and fashion know-how.” Because of that, Japan is often portrayed in Western writings as “either upholding tradition or passively adopting Western styles and social systems, in contrast to Europe and America, who have been portrayed as leading Japan into modernity.”

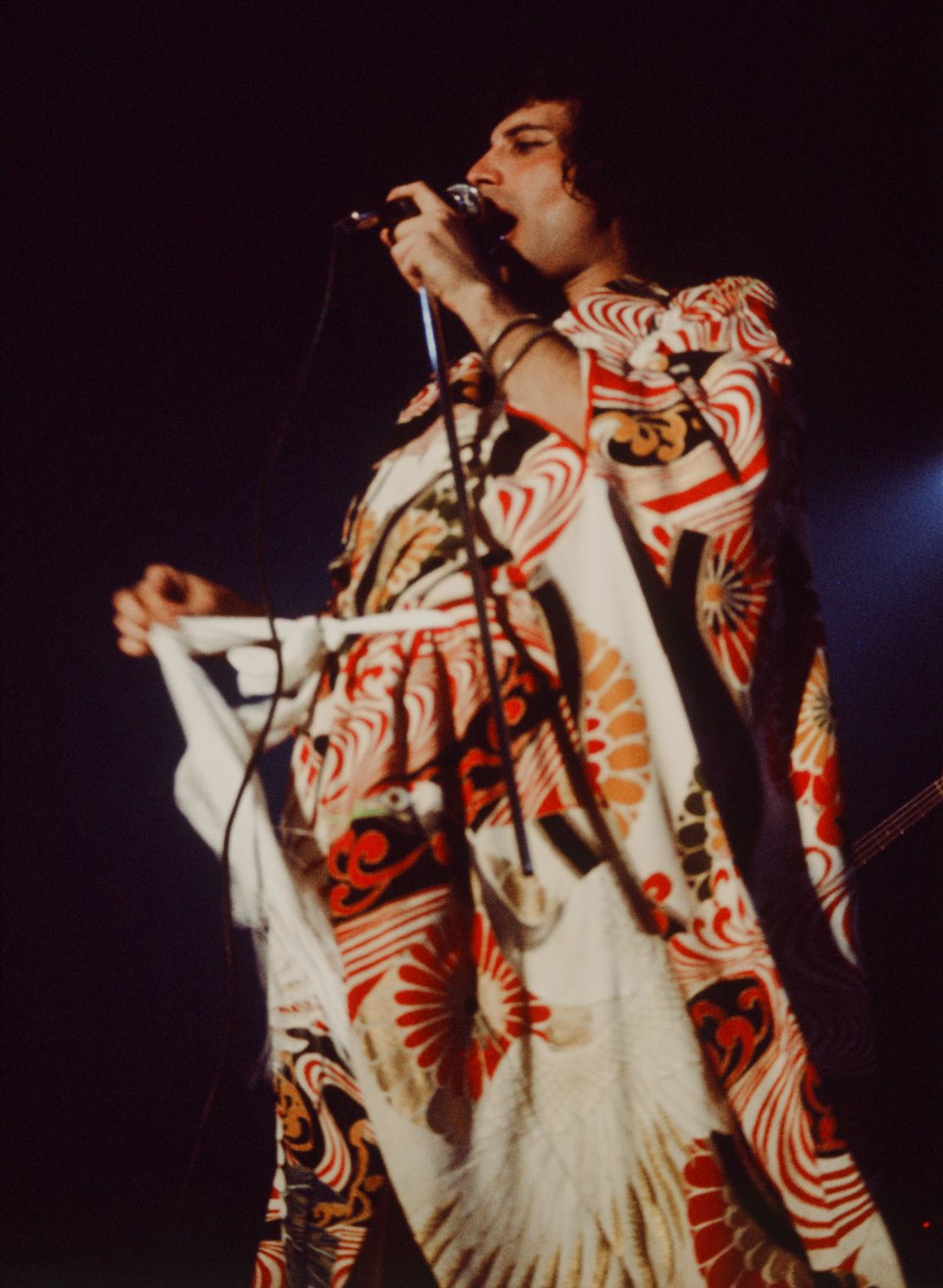

Walking through the final gallery of the “Kimono” exhibition, a showcase of contemporary kimonos and kimono-esque looks, it’s clear the cultural exchange hasn’t stopped: a hand-painted, hooded kimono by emerging British designer Milligan Beaumont, commissioned specially for the show, is covered in Japanese iconography and lyrics from singers including Lana Del Rey and Amy Winehouse; while a voluminous John Galliano-designed Christian Dior ensemble from 2007 channels both the swing coat pioneered by the house’s founder and the highly formal Japanese uchikake, or outer-kimono. A gray Thom Browne suit with a Japanese scene appliquéd across is juxtaposed with a Fujikiya wool kimono styled with a crisp white shirt and red silk tie.

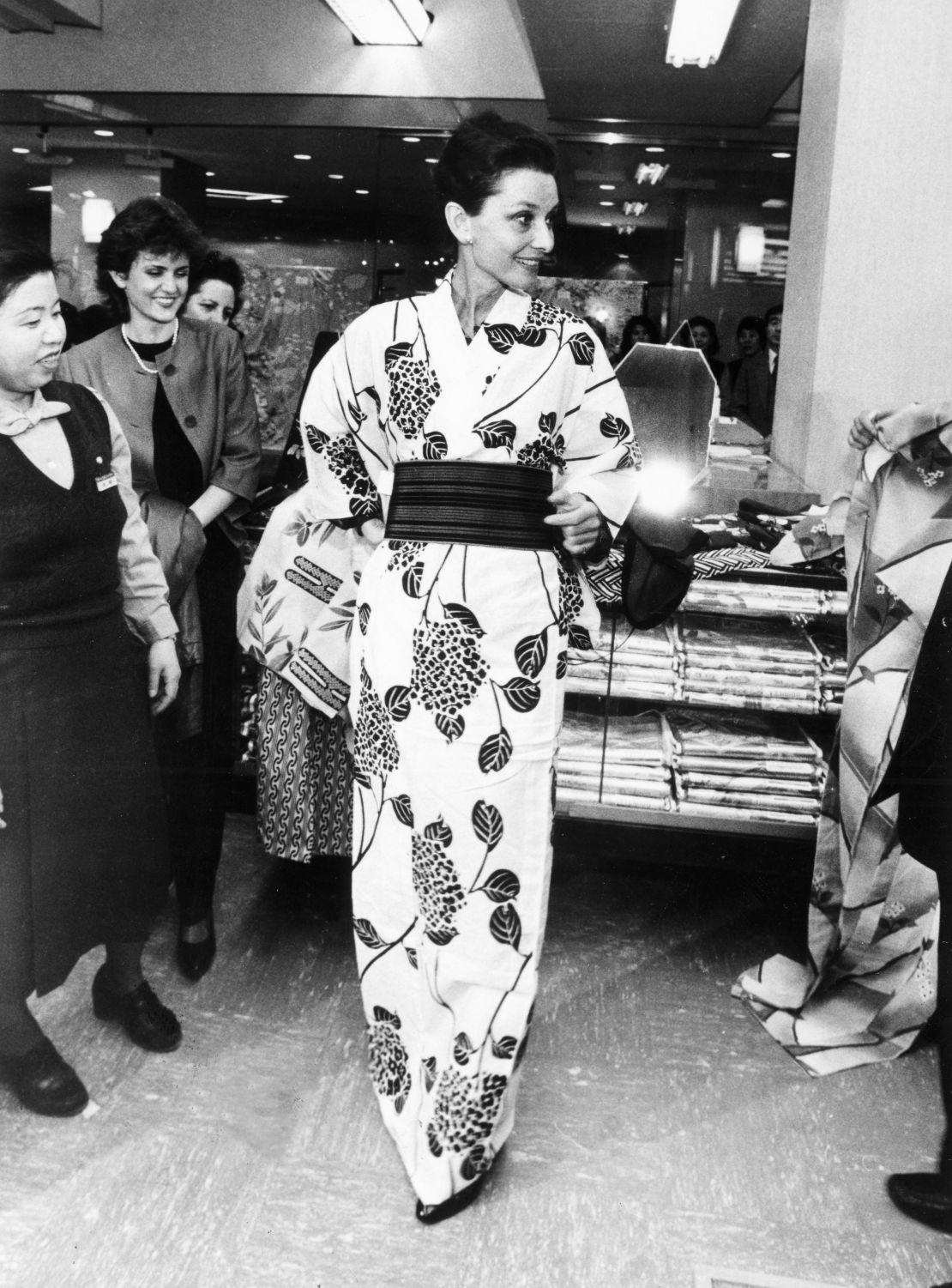

This ongoing dialogue, wherein both parties benefit and borrow from each other, sets the conversation around the kimono apart from that of other contested garments. Two imperial powers adopting one another’s aesthetics without severing the ties to the originator is quite a different thing from a party with more power surreptitiously borrowing from a marginalized group. This may explain why, today, many in Japan are generally unfazed by foreigners’ decision to wear kimono.

“There are people who are truly offended by cultural appropriation and their feelings are completely valid, but in Japanese culture, it just doesn’t work the same way,” said Manami Okazaki, a Tokyo-based fashion and culture writer. “(The Japanese) are really trying to share Japanese culture, so it’s very, very different to a minority culture that feels like they’ve had something stolen from them.”

If anything, Japan’s contemporary kimono designers are hoping more people will take an interest in the garment. After World War II, the kimono all but disappeared from everyday life and came to symbolize national pride and tradition rather than fashion. More recently, however, spurred by the rise of street style in the Harajuku district, the garment has seen a resurgence.

But context, Okazaki points out, is key. While a Japanese person living in Japan may think nothing of a non-Japanese person incorporating a kimono into their look, a person in a setting where they’re a minority or marginalized may feel differently.

This was evidently the case in 2015, when the Boston Museum of Fine Art found itself at the center of a cultural appropriation row when it introduced “Kimono Wednesday.” As part of the public program surrounding its “Looking East: Western Artists and the Allure of Japan” exhibition, the museum invited visitors to try on replicas of the red kimono worn by Claude Monet’s wife in his painting “La Japonaise.”

After a group of protestors accused organizers of racism and cultural appropriation and incited backlash on social media, Kimono Wednesday was swiftly canceled, though Jiro Usui, the deputy consul general of Japan in Boston, told the Boston Globe that the consulate “did not quite understand the point of the protest.”

“Whether or not you think it’s cultural appropriation or not depends on who you are, and it depends on what kinds of power relationships you’re trying to negotiate,” Cheang said. “But it also depends very much on how you experience your own sense of self in relation to the act of cultural appropriation that’s going on. So if your sense of self is affected negatively by what you’re seeing, then it’s clearly going to provoke a reaction, and the person who’s doing the cultural appropriation – in this case wearing the kimono – needs to be sensitive to that.”

Jackson says this is something she and her team were conscious of during the development of the exhibition. The catalog offers essays that explore the kimono’s social and cultural histories, and Jackson said she made a point of asking the featured Japanese designers how they felt about non-Japanese people wearing their clothes.

“It’s never a straightforward dichotomy – East versus West, or something that’s traditional versus something that’s avant-garde. I think there are quite porous borders there,” Jackson said.

“I don’t think you can be critical of people because they don’t understand the background, but hopefully they’ll come to the V&A and learn that background.”

“Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk” is on at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London until June 21, 2020.