A non-hormonal birth control capsule that women can insert just before sex. A rape kit that gives victims more agency and streamlines the evidence collection process. An overhauled design for a 150-year-old tool used in postpartum vaginal tearing.

These designs are just some of the finalists announced this week in the 2021 Index Award, and their creators hope to make the future of medicine and sexual health more equitable for all genders.

“There is still so much shame around female, trans and non-binary bodies that impose harmful barriers to healthcare,” said Liza Chong, CEO of the award’s Danish nonprofit organization, The Index Project. “A culture of silence persists around a number of important topics, ranging from women’s sexual pleasure to the long-term implications of childbirth, serving to sideline vital conversations and deny people access to helpful and even life-saving resources.”

Hosted since 2005, the biennial awards focuses more broadly on how design can solve crucial global issues – past winners include the language app Duolingo and the 3D-printed Mars habitat MARSHA – but with one category focused exclusively on design for the body, finalists and winners often tackle gendered issues in medicine that have long been ignored or are considered taboo.

Two years ago, for instance, the finalists included the AI-powered chatbot Raaji, which answers questions on menstruation, mental health and sex for girls and young women in developing countries. This year, two women doctors, Dr. Sara Saeed Khurram and Dr. Iffat Zafar Aga, have been recognized for their Pakistani telemedicine company Sehat Kahani, which uses an all-female network of doctors. According to the Index Award, the e-clinics provide accessible healthcare and attempt to combat the so-called “doctor bride” phenomenon, where many female medical students in the country forgo their careers, under pressure to prioritize motherhood.

Long overdue redesigns

This year’s finalists hope to make seismic changes in the world through a single thoughtfully designed product that, in some cases, update a long-neglected area of medicine. Take the Hegenberger Speculum, for instance, which claims to make it easier for midwives to stitch perineum tears that occur during birth – something 9 out of 10 women experience, according to the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) – and is made out of silicone instead of metal for more comfort for the patient. The current speculum had not been updated in a century and a half, according to its creator, Malene Hegenberger.

“It’s quite a taboo subject,” Hegenberger told the Danish media outlet Avisen in 2018. “Women generally don’t want to be a bother and there’s a lot of other stuff to focus on after childbirth. They put themselves aside and put the child first. I think that’s why there hasn’t been much done about it.”

Meanwhile, the company Cirqle Biomedical is in the beginning stages of testing a new form of birth control that, if successful, could revolutionize the field since hormonal birth control was introduced to the market in 1960.

“Women’s health has been under-prioritized and neglected for decades,” said CEO Frederik Petursson Madsen over email. “Despite having billions of users, there has been very little innovation in the industry.”

Its product, Oui, is a gel capsule that women can insert a minute before sexual intercourse and lasts for up to five hours, according to the company. It’s non-hormonal, made of water and chitosan biopolymers, and works by thickening cervical mucus, preventing sperm from migrating past the vaginal canal.

Oui is meant to be less invasive than implants like Nexplanon and IUDs, which require in-office procedures to insert and remove; provide more flexibility than a daily regimented pill; and cut down on side effects that are common with hormonal birth control, from associations with depression to a higher risk of blood clots and stroke.

“The necessity for women who take contraception is to prevent pregnancy, and because this need was the priority and there has been a lack of good alternatives, women (have) had to accept and put up with the side effects,” said design manager Marie Lyhne in an email interview.

Addressing systemic issues

Designer Antya Waegemann has taken on a deeply complex problem that reaches across healthcare, policing and legal systems in countries around the world including the US: the backlog of hundreds of thousands of untested rape kits – DNA collection kits which are crucial to identifying and charging sexual assault perpetrators.

While sexual assault affects people of all genders, the UN estimates that nearly one in three women over the age of 15 globally have experienced sexual violence, and the statistics for transgender people are even starker at one in two, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC).

In the US, the process for testing rape kits is plagued with issues from end to end, from laboratory delays to police destroying them. The problems start right from the beginning, according to Waegemann, who spent a year as a sexual assault advocate at New York Presbyterian Hospital, with confusing package design and collections that can take hours for victims who have just been through a severe trauma.

“It became so clear to me through that process, and also reading the instructions myself, how truly difficult it was to complete this kit,” she said in a video call.

Though Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE) are trained to collect the rape kits, there is a national shortage of these types of nurses, and many hospitals will turn away victims if they don’t have the staff – or the kits – available. According to Waegemann, she rarely saw a SANE professional on staff while volunteering; instead, it was mostly ER doctors and nurses handling the process. They tend to be much less familiar with the kit, Waegemann said, which was first designed in the 1970s and can include up to 16 different envelopes for collecting genital swabs, pubic hair combings and fingernail clippings, among other things.

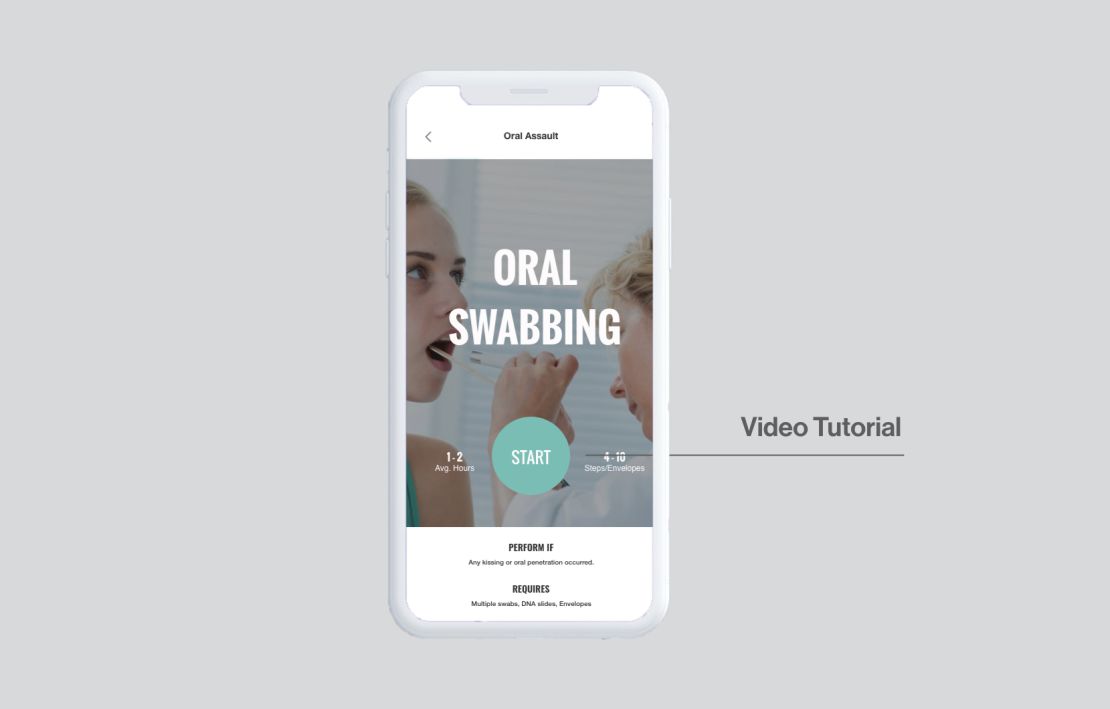

Waegemann’s redesigned kit offers color coding and clear instructions for healthcare providers, as well as an app for the victims to follow along with the process and understand each step.

But Waegemann also wants to make processing and testing the kits easier and faster for police and lab technicians, as well as provide immediate support for victims. Her company, Margo, is working on other products as well that aim to reimagine the system entirely, from how kits are tested and, importantly, tracked, once they leave the hospital, to an app that gives people information on how and where to get tested if they’ve been assaulted.

“The designs I have created of course consider the entire system,” Waegemann said in a follow-up email. “But they are really about taking an entire process that is designed to exclude victims from taking control and seeking justice, and re-designing the aftermath…”.

“I really believe that a product itself can change a system in a way that sometimes policy cannot,” she said in the call.

On September 30, five winners will be announced from the 46 total finalists. The Index Award lists over €200,000 ($244,000) in prizes for the winners, as well as the potential for the organization to help fund their work moving forward.

Top image: A Oui capsule by Cirqle Biomedical

See all of the finalists for the 2021 Index Award here.