In the late 1980s, mobile cinema businesses were burgeoning in Ghana, bringing film screenings to villages and rural areas without theaters or electricity. These makeshift “video clubs” – usually made up of a diesel generator, a VCR and a TV or projector loaded onto a truck – would travel around the country showcasing Hollywood and Bollywood blockbusters, as well as West African films.

To attract viewers, the video clubs needed to advertise their offerings. But they did not have the original movie posters, or the means to print alternatives – the country’s military rulers had even restricted the import of printing presses.

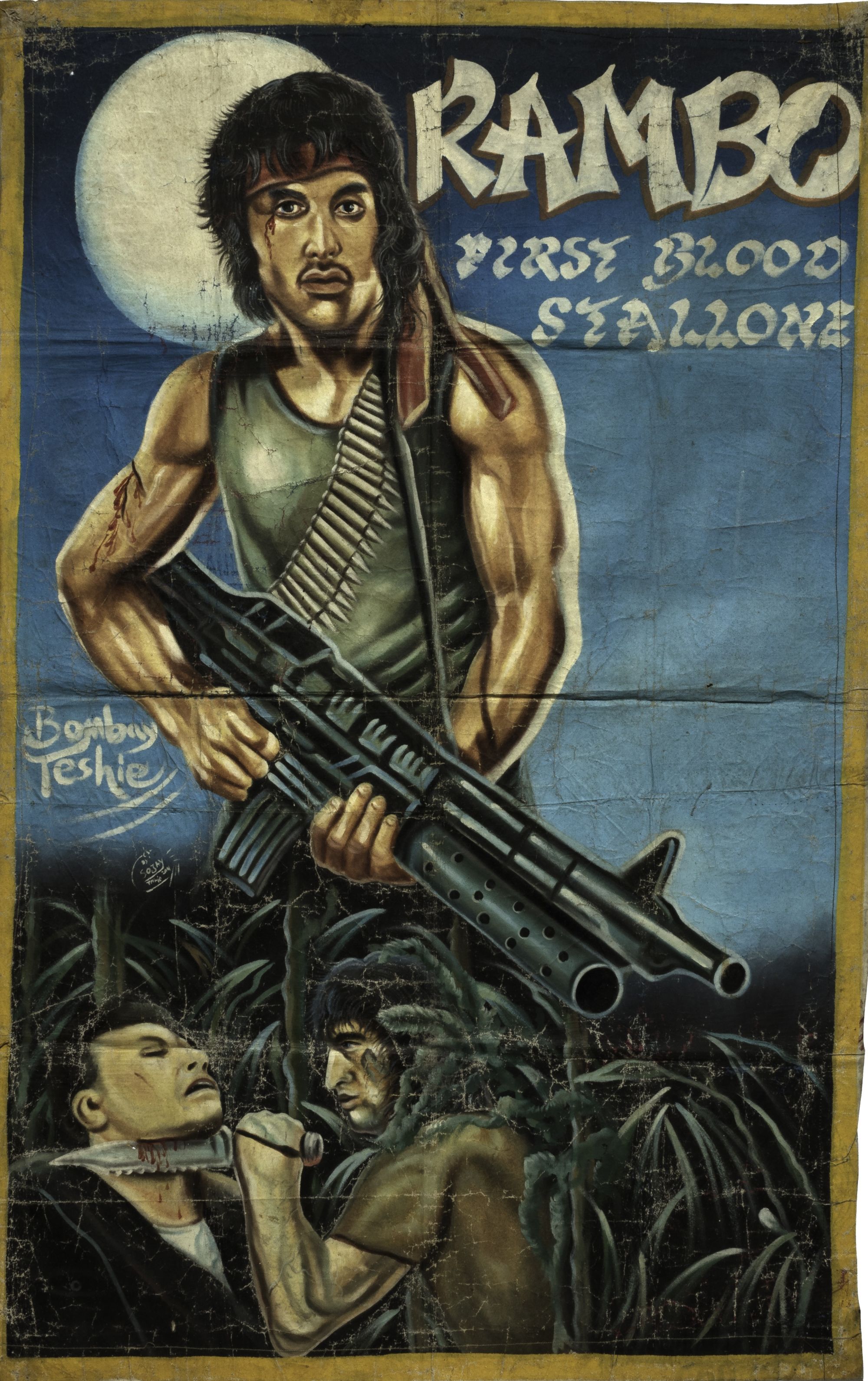

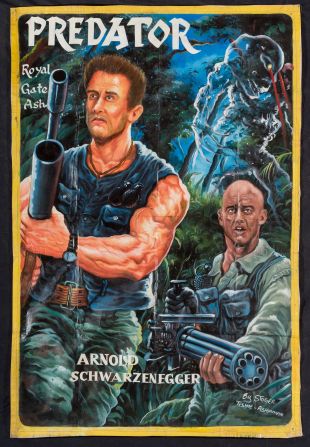

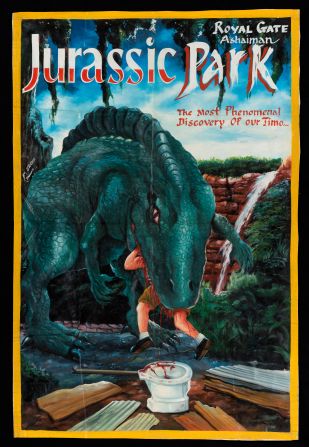

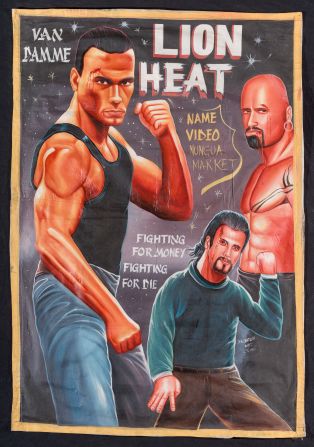

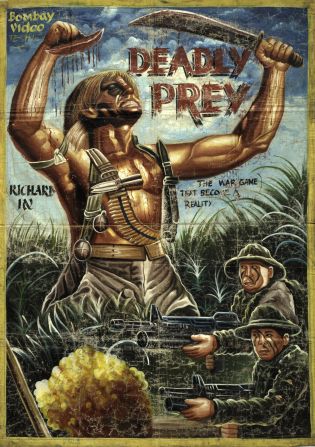

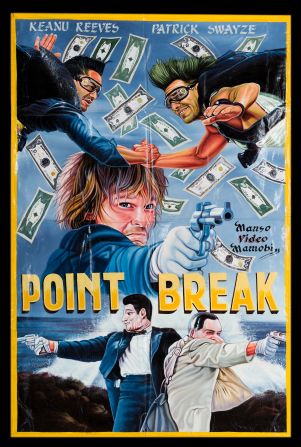

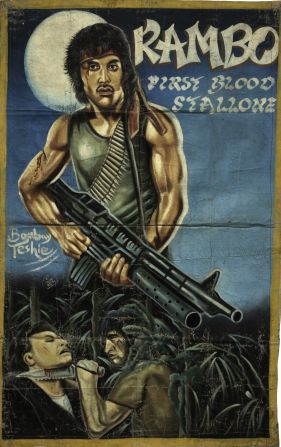

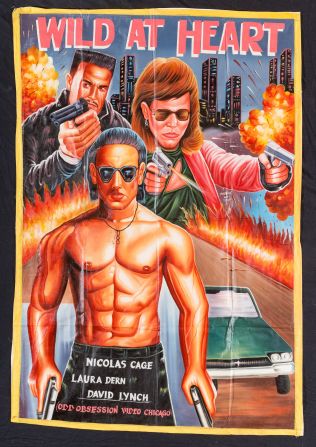

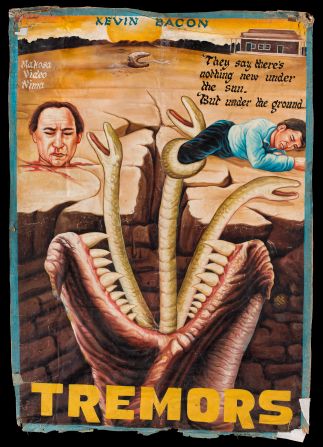

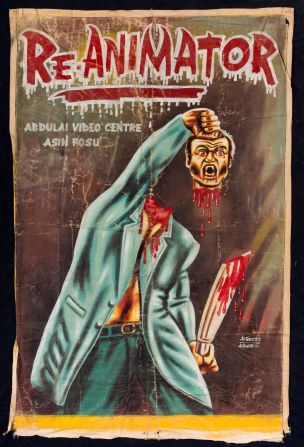

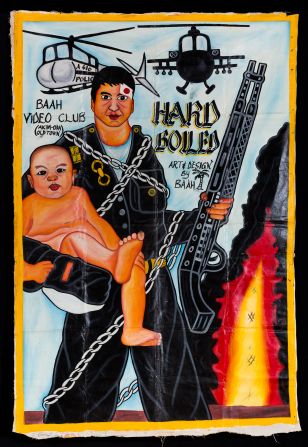

So they made their own, commissioning local artists to hand-paint them on used flour sacks. They were large, usually 40 to 50 inches in width, and 55 to 70 inches in height.

The posters have since made ripples in the art world, with early originals commanding high prices from collectors.

The unexpected art of Ghana's hand-painted movie posters

The works are famous for their garish, exuberant style, full of muscles, blood and exaggerated features.

“They were designed to sell movie tickets, it was all about getting people through the doors,” said Brian Chankin, a dealer and collector, on the phone from Ghana. “So the vibe really was to try and make each poster as unique as possible, not to mention as crazy as possible.”

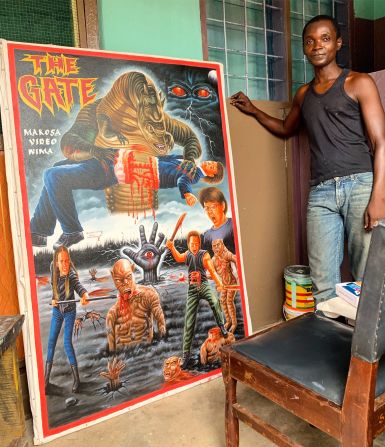

Occasionally, artists took creative license by depicting events that weren’t in the films. “I sometimes watched the movies and picked some actions from it,” said Heavy Jay, an artist who owns a studio in Teshie, near Ghana’s capital Accra, in an email. “But if the movie was so boring, then I had to do it by my own imagination, which mostly features some images and actions that (were) not in the movies, to attract more people to go watch them.”

By the 1990s, the height of the movie club business, several dozen artists were employed to produce the posters. Some of the most popular artists – or their pseudonyms – included Joe Mensah, Nyen Kumah, Leonardo, Socrates, Death is Wonder, Frank Armah and D.A. Jasper.

Brian Chankin began collecting the posters about 10 years ago, just as global interest started building around them. He displayed them on the wall of a video store he owned in Chicago.

“People started wanting to buy them off the wall, so we ended up selling quite a few,” he said. “I was able to gain a little following with them, so I started buying more and more with any money I had. Over the years, hundreds and hundreds of posters have come through my hands, and many of them I keep for my collection.

“There’s some that would go for well into the thousands if I decided to sell them, but those are the ones I am certainly not interested in selling. I know that other people have sold these posters for upwards of $50,000. Anything from the 1980s is just incredibly scarce and incredibly hard to find at this point.”

Demand for video club posters in Ghana started dying out in the mid-2000s, when home viewing became more widespread and printing became more practical than commissioning original artworks, which took days to make. Since then, many artists have quit the trade, Chankin said. But some have kept the tradition alive and are now working on commission, either making copies of original posters or painting entirely new ones of both old and new movies.

In 2015, Chankin opened Deadly Prey Gallery, a Chicago-based studio that works with Ghanaian artists. Prices for commissioned posters vary from $300 to $600, and the most requested are from the big 1980s action blockbusters that made the posters famous. “Predator, Terminator, anything with Kurt Russell, anything with (Jean-Claude) Van Damme,” said Chankin, adding: “Horror is arguably the most popular genre.”

With interest seemingly on the rise, the posters are now easy to find on online. But, Chankin warned, buyers should beware of modern copies masquerading as old originals.

“There are always bootlegs – they usually try to make the posters look older than they actually are,” he said. “Those ones I could spot in a second, but other people might not be able to.”

This article was originally published in October 2019.