Editor’s Note: Noah Charney is an international best-selling author and professor of art history. The views expressed here are the author’s own.

Last month, the board of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston issued a statement that they would double the longstanding reward for the return of artworks stolen from their premises back in 1990. They are now offering a cool $10 million, but with a time limit: the deal is only good until Dec. 31.

This is the latest chapter in an epic saga of the biggest art theft in peacetime history. Thirteen artworks, valued at between $300-500 million (if sold legitimately on the open market) were lifted from the museum during an 81-minute window in the night after the St. Patrick’s Day revels, in 1990.

But while this reward doubling has made headlines, it is in my view an act more of frustration and desperation than a sign of impending solution.

When the original $5 million reward was set, it stirred up many leads, almost all of them dead ends. Myriad theories have swirled around who was behind this crime, for surely it was some larger organized crime group, more elaborate than just the two thieves disguised as policemen who bluffed their way into the museum, tricking security staff into opening the door without first checking with the police department.

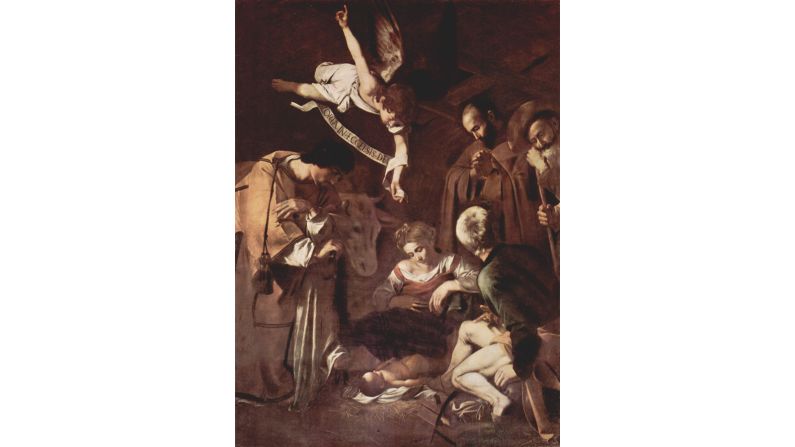

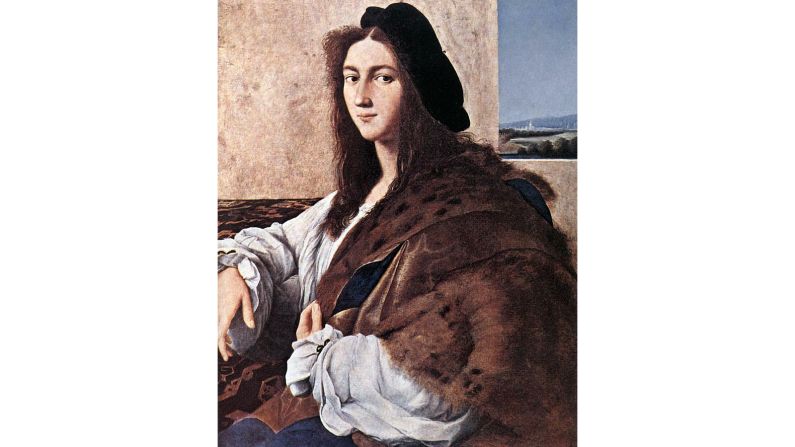

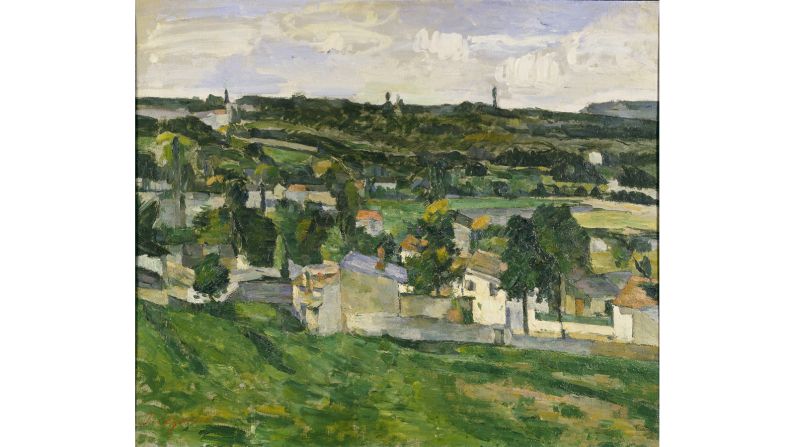

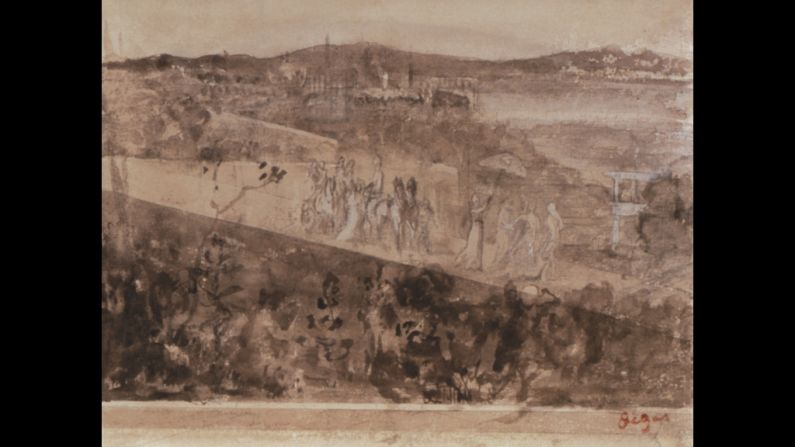

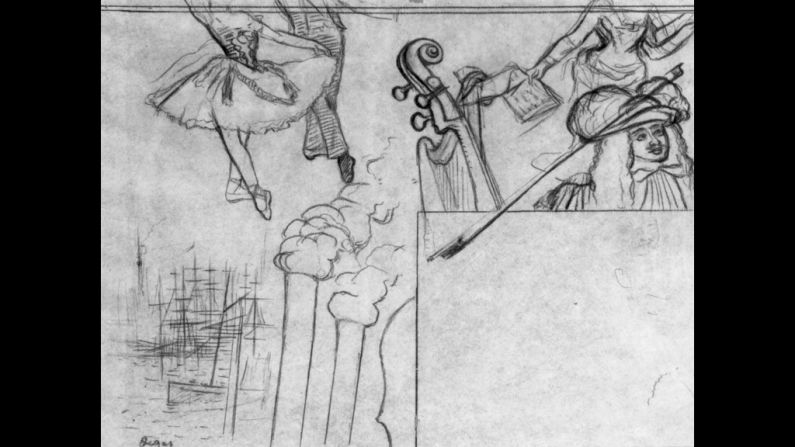

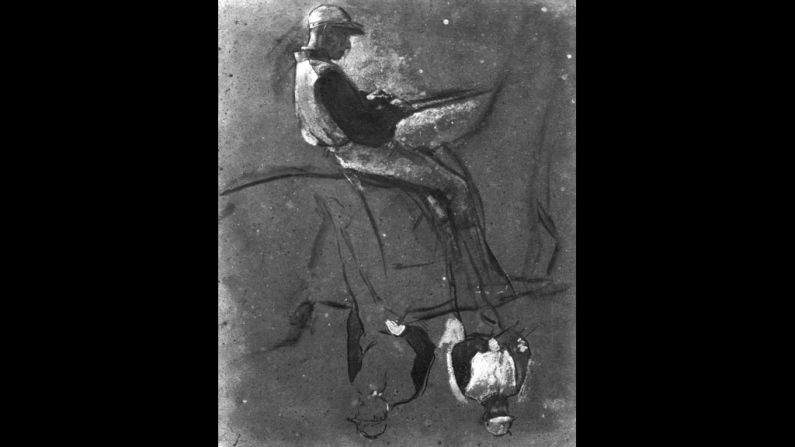

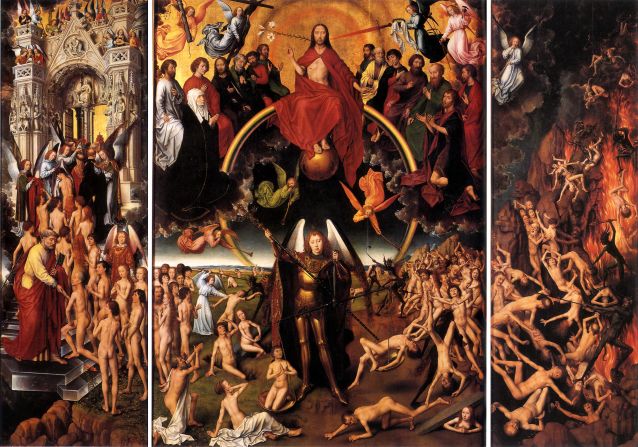

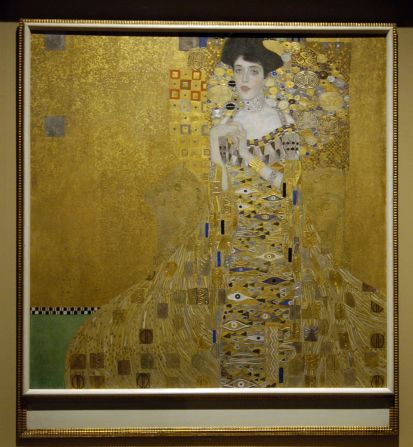

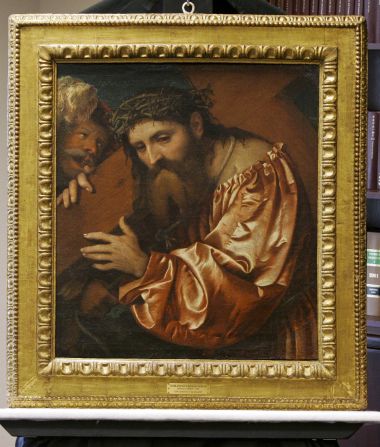

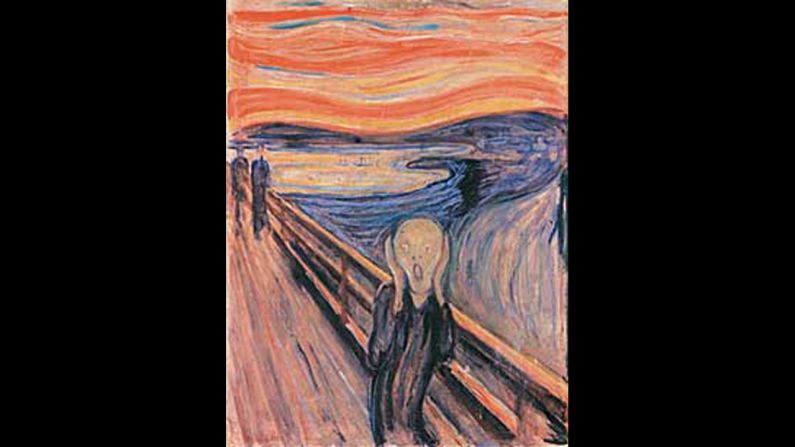

The criminals got away with works including Rembrandt’s “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” Manet’s “Chez Tortoni” and Vermeer’s “The Concert” headlining their haul.

The search for stolen masterpieces

It was a complicated crime, too. There were details that suggested that the thieves knew exactly what they were looking for, that they had been instructed what to steal. They bypassed some works of equal or greater value (and perhaps more portable) than the art they took.

Tracking the haul

In 2013, on the 23rd anniversary of the Gardner art heist crime, the FBI held a press conference that sounded promising. They revealed some new information considered sensational by the media at the time.

As a professor specializing in the history of art crime, I get a lot of questions about this, the highest-profile art heist since the theft of the Mona Lisa. I know much about the soap opera that has been going on behind-the-scenes for many years, and I know how to read police press conferences and offers of reward.

While the press conference was interesting to update the general public, those of us in the know have been aware of all that was revealed, and for some time. In the press conference, couched in terms of an appeal for information, it was revealed that the the Gardner works appear to have been transported through Connecticut and Pennsylvania, and were offered for sale in Philadelphia.

This is useful information, as some theorists suggested that the works were destroyed, or had been shipped to Ireland, with IRA links to the theft.

That the art was offered for sale means that it was not immediately brought to the secret sitting room of some Thomas Crown or Dr. No (who, in the first James Bond film, has a hideout decorated in copies of real stolen art), where it has since remained. The careful phrasing of the press conference gave the impression that, while progress had been made in terms of learning some of the backstory, the investigation appeared – at least to me – to be no closer to the truth. Much is known, but not quite enough to recover the art.

The risks of rewards

For years now, driven by desire for glory – for the Gardner hoard is the Holy Grail for art detectives – and probably by a healthy interest in the eyeopening reward, a number of prominent investigators, in addition to the FBI, have been searching for clues, and have made enormous strides.

There are several fine books written about the ins-and-outs of the case, but the general consensus is this: The thieves, and those who know where the art is hidden, are dead. It remains to be seen if anyone still living knows the hiding place of the loot. That’s what the reward, and increased attempts at stirring public interest, aim to do.

Rewards, in the world of art theft, are sharp-handled swords. They can work well, or they can hurt the handler.

In 2008, a theft of gold statuary from the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia was solved thanks to the museum board posting a reward that was worth significantly more than the raw material value of the gold stolen. The thieves might have initially intended to melt their loot, thereby erasing the evidence. But the lure of the reward stayed their hand long enough for the police to catch them.

On the other hand, rewards can backfire. In 1975, 28 paintings were stolen from the Gallery of Modern Art in Milan. A reward was offered, the paintings were returned (by associates of the thieves) and paid (to associates of the thieves) and the art was placed back on display. Within months, thieves broke in again and stole 35 works, including many of the same paintings. It was likely the same thieves dipping into the same well twice. The fruits of this second theft have never been recovered.

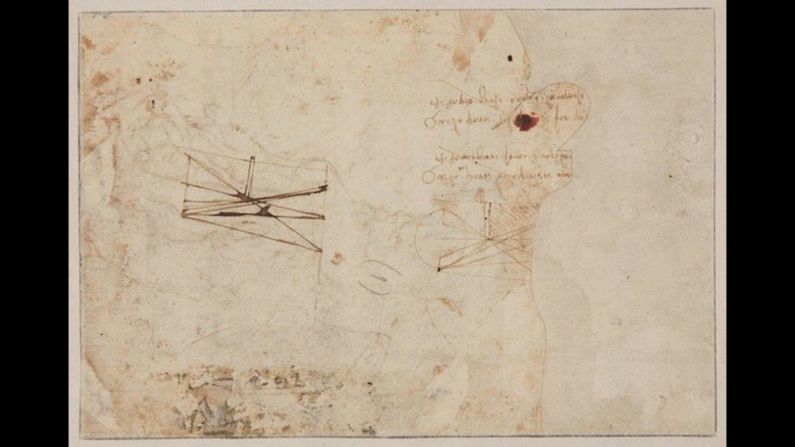

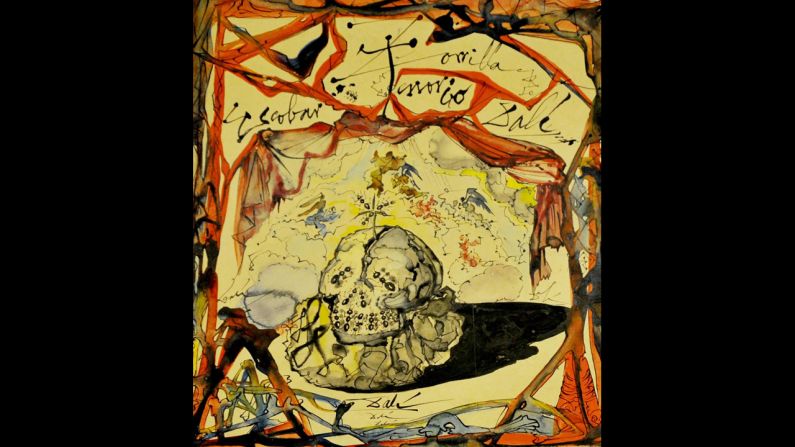

Lost and found: Incredible works discovered

There is also the complicated issue of how to swap the stolen art for the reward without granting illegal amnesty to the thieves, and without appearing to be paying a ransom, which is illegal in many countries.

So, will the lure of $10 million, and a closing window of opportunity, suddenly shake the art out of the woodwork, and get results, when $5 million led to no tangible results? Anyone, aside from the thieves themselves, is eligible for the full reward, but only if all 13 objects are returned in acceptable condition.

The answer is likely no, for $5 million is already so robust a reward, so far beyond the amount that thieves could possibly get for such famous art on the black market (where experts estimated that stolen art, if a buyer can be found at all, goes for around 7-10% of its estimated legitimate auction value, with more famous works all but impossible to sell, full stop), that doubling it does not suddenly provide an incentive that had previously been absent.

I have no doubt that the art will eventually be found. But it will be a matter of luck, of stumbling on its hiding place at some unknown point in the future, of accidentally pricking oneself while wading through a haystack, and thereby finding the lost needle.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story contained unsupported details regarding the night of the heist and subsequent investigations, which have now been removed.