Story highlights

The Science Museum hosts first major UK exhibition of Joan Fontcuberta's controversial photography

Known for playing with reality and fiction, the artist has fooled institutions with his 'false' records of strange animals

Fusing science with storytelling, Stranger than Fiction promises to delve deep into the mind of a renowned prankster

There’s only one way to start an interview with Joan Fontcuberta. Why, I ask him, should I believe a word he says?

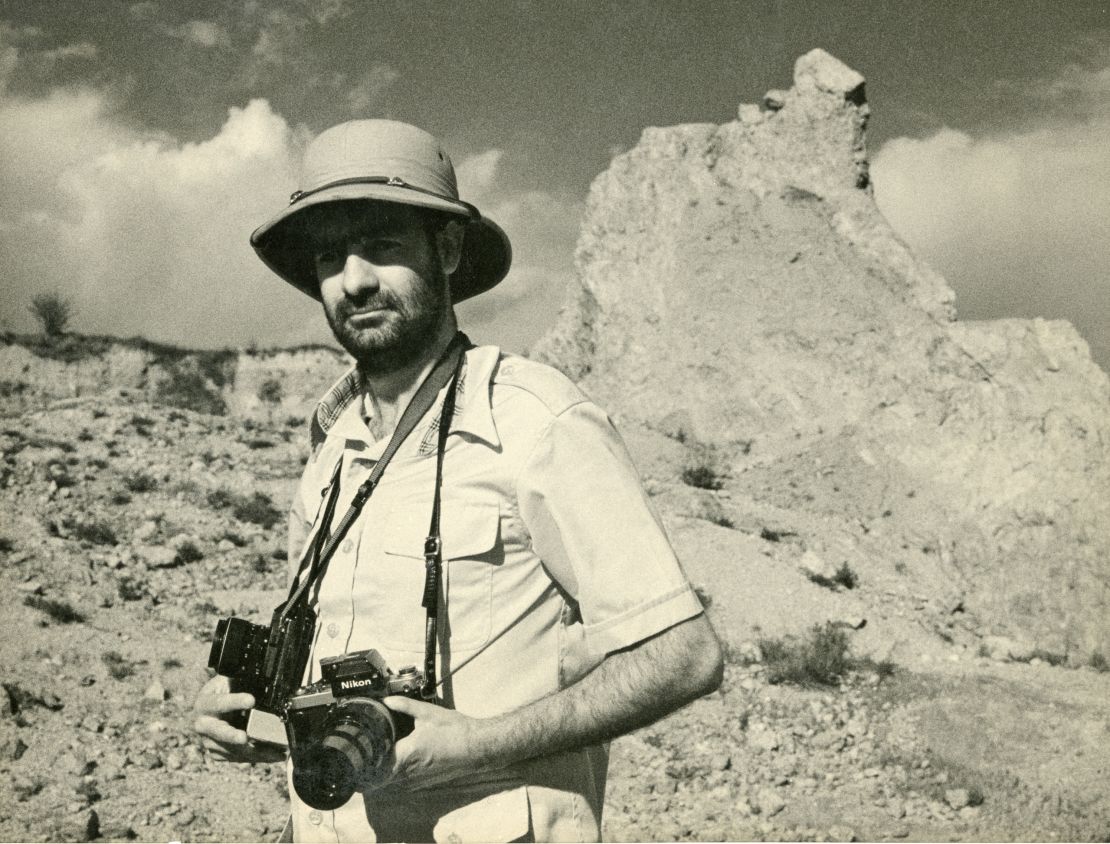

“I like that question,” says the pre-eminent Spanish conceptual artist, when we meet in the café at London’s Science Museum.

“I believe that doubting is the first step to rational knowledge. Not doubting implies submission, which is dangerous.”

If truth be told, there are more reasons to doubt Fontcuberta than anyone else.

After all, this is the man who has pranked, dodged and bamboozled his way to the top of the art world.

Fake files

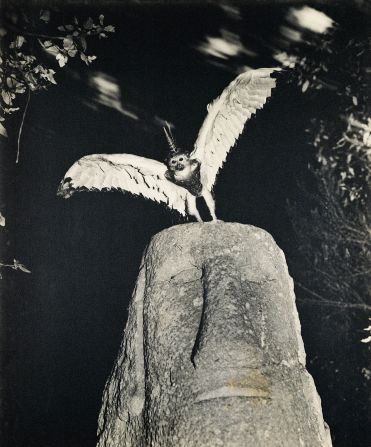

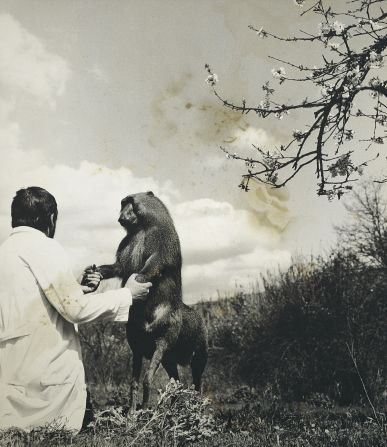

In 1987, in an exhibition called Fauna, he pretended that he had stumbled across the hidden archives of a German zoologist called Dr Peter Ameisenhaufen, which contained samples of animals previously unknown to science.

Ten years later, he convinced the world that a Russian cosmonaut had been lost in space in 1967, and the disappearance covered up.

The hoax fooled Spanish TV, which reported it as fact before realizing that the cosmonaut’s name, Ivan Istochnikov, was a Russian translation of the artist’s own name.

And at the age of 59, the diminutive, bearded Fontcuberta has lost none of his enthusiasm for “playing with conceptions of authority”.

Last month he pretended to “curate” an exhibition in Paris called the Trepat Collection, which mixed genuine photographs from the Forties and Fifties with his own pastiche, passing it all off as a single archive.

From now to November, the Science Museum – that bastion of empiricism – is hosting a major retrospective exhibition of Fontcuberta’s work, entitled Stranger than Fiction.

Read: When ‘Desperate Housewives’ meets Tim Burton in a bakery from hell

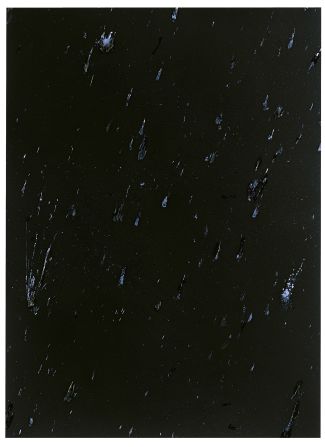

It starts with taxidermy, including a squirrel with a snake’s tail and a winged goat; moves on to photographs of “constellations” that are actually specks of dust on a car windscreen; and ends with pictures of the artist himself performing “miracles”, such as levitation, in the garb of a Christian monk.

The exhibition is visually arresting, subversively humorous, and infernally clever. It is also deeply unsettling.

So what is it about Fontcuberta that makes him so intent on fooling the world?

Explosive moment

“When I was 13, I was experimenting in chemistry and I blew up my hand,” he says, sipping espresso.

“I was interested in testing things, and was building rockets with gunpowder. Pyrotechnical stuff. It was wonderful, very effective. But one Sunday my parents were away traveling, and I was alone with my cousin.

“And I blew up my hand.

“Psychologically, this was very strong. It changed my whole life. I started hiding my hand so people didn’t see my problem, which produced very complex human relationships. Life became about multiple truths.”

Because of his damaged hand, he continues, he was excluded from military service, giving him “time to play with photography”.

As he couldn’t handle the camera quickly, photojournalism was out. So he became a “meditative photographic artist”.

Read: 7 of the world’s most beguiling bus stops

He shows me the stump of his left index finger. I am skeptical.

He has told other journalists that he lost his finger while building a “homemade bomb”.

Is he taking me for a ride – or them? (Or has this interview made me paranoid?)

“Well, you could consider it a bomb,” he says.

“Half and half. I used to make explosive artifacts and throw them out of the window. I also did underwater explosives with sodium. I made miniature submarines and ships, and blew them up with mines.”

The world of Joan Fontcuberta is strange indeed.

Propaganda machine

Bombs and rockets aside, it was the political climate in which he came of age that informed Fontcuberta’s career.

Prior to 1975, Franco ruled Spain as a dictatorship.

The climate of repression and the ubiquity of propaganda in Fontcuberta’s childhood led him to a preoccupation with challenging authority in all its forms.

“Franco is no longer the enemy, but to me he was just one particular historical manifestation of authoritarianism,” he says.

“I struggle against every type of authority, in religion, science, politics, and art. I don’t believe in hierarchies.”

Read: Surprise designs behind the Iron Curtain

Does that make him a Socialist? “I am a bizarre combination of socialism with anarchy thrown in,” he says.

“But I’m also a pragmatist. I recognize that a representative democracy is necessary. But it has risks, and we must keep paying attention to the system. That’s why I call myself an anarchist. I’m trying to fix the problems of authoritarianism that might occur in a representative democracy.”

An irreverent eye

He illustrates this by citing photography. Documentary photojournalism, he says, is valuable as an “eye in the distance”, showing people things to which they otherwise would never be exposed.

His role is that of the “oculist”, ensuring that the eye remains accurate by questioning the veracity of what it shows us.

Religion is a favorite target.

Although he was brought up a Catholic, as a teenager he experimented with Zen and other alternative religions, before becoming a committed agnostic.

“The reason I often joke about religious belief is that it brings us to dogma, and to me dogma is stupidity,” he says.

“I don’t agree with faith. I think we should keep a questioning mind.”

So what next for Fontcuberta? “I have lots of ideas and not enough time,” he says.

“People often get angry with me, and accuse me of being a liar. But I never lie. I just create ambiguities and encourage people to question things.”

He sighs, and drains his coffee. “My mother is always warning me that one day I will finish in jail. But I have more trust in humanity than that.”

Joan Fontcuberta: Stranger than Fiction is showing at the Science Museum, London, from 23 July – 9 November 2014

Touch it, you know you want to. The hands-on world of digital art

Picasso’s painting unearths a secret

Sexy and sophisticated: China’s iconic dress

When ‘Desperate Housewives’ meets Tim Burton in a bakery from hell