Editor’s Note: Owen Hatherley is the author of Militant Modernism: A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain; and Uncommon, about the pop group Pulp. He writes regularly on the architecture for the Guardian and New Statesman. His Landscapes of Communism: A History through Buildings is out now, published by Allen Lane.

One of the most common ways of dismissing “communism” is to point to its monolithic modern architecture, and one of the most common ways of dismissing modern architecture is to point to its association with Soviet communism.

In the UK, for instance, blocks are habitually described as “Soviet” if they are repetitious and use reinforced concrete. Meanwhile, in the USSR beautiful historic cities like Tallinn were surrounded by what are now “museums to the mistreatment of the proletariat” (as the historian Norman Davies recently put it); and it is probably these blocks, seen on the way from the airport en route to a holiday in Prague, Krako?w or Riga, that people mean when they talk about “commieblocks.”

Nothing is seen to discredit the entire project of building a non-capitalist collective society more than those featureless monoliths stretching for miles in every direction, and their contrast with the irregular and picturesque centres bequeathed by feudal burghers or the grand classical prospects of the bourgeois city.

This, it is implied, is what people were fleeing from when they pulled down the Berlin Wall.

It is ironic that these “inhuman” structures, barely even recognizable as “architecture,” are usually the result of what was one of the Soviet empire’s most humane policies – the provision of decent housing at such a subsidy that it was virtually free – rents for this housing was usually pegged at between 3 and 5 per cent of income.

They begin to be built en masse in the second half of the 1950s. Reformers like [Soviet Union Premier Nikita] Khrushchev promised they would create – for literally the first time in nearly all of these cities – decent housing for all workers, where they wouldn’t have to share rooms or flats with other families, where they would have central heating, electricity, warm water and other then-unusual mod cons.

This needed to be done, and fast, as both the war and a breakneck industrial revolution had caused massive urban overpopulation.

As they would have known from [Karl Marx’s] Capital, or from [Friedrich] Engels’ Condition of the Working Class in England, the first industrial revolution led to terrible housing conditions, with hundreds of thousands of people crammed into cellars and courts. They promised to use exactly the industrial forces that had created this to provide the solution – mass-produced housing, made in factories just like cars or anything else.

By the 1970s, there was more factory-made housing being built in the USSR than anywhere else in the world.

So what went wrong?

The projects always look magnificent from the model, and superb from above: there, the patterns of the blocks are clear, the parkland and the lakes look genuinely verdant – abstract images of modern luxury.

But the ground is – at least in the conventional view – illegible. Instead, slabs are surrounded by scrubland, without viable public space or coherence.

This is how the council estates of the West have often been seen, too – a top-down imposition from architects and planners upon the unknowing workers and peasants, who lost their baby (community life in a place with a distinctive identity) with the (surely undeniably filthy) bathwater.

Read more in Landscapes of Communism: A History through Buildings, out now.

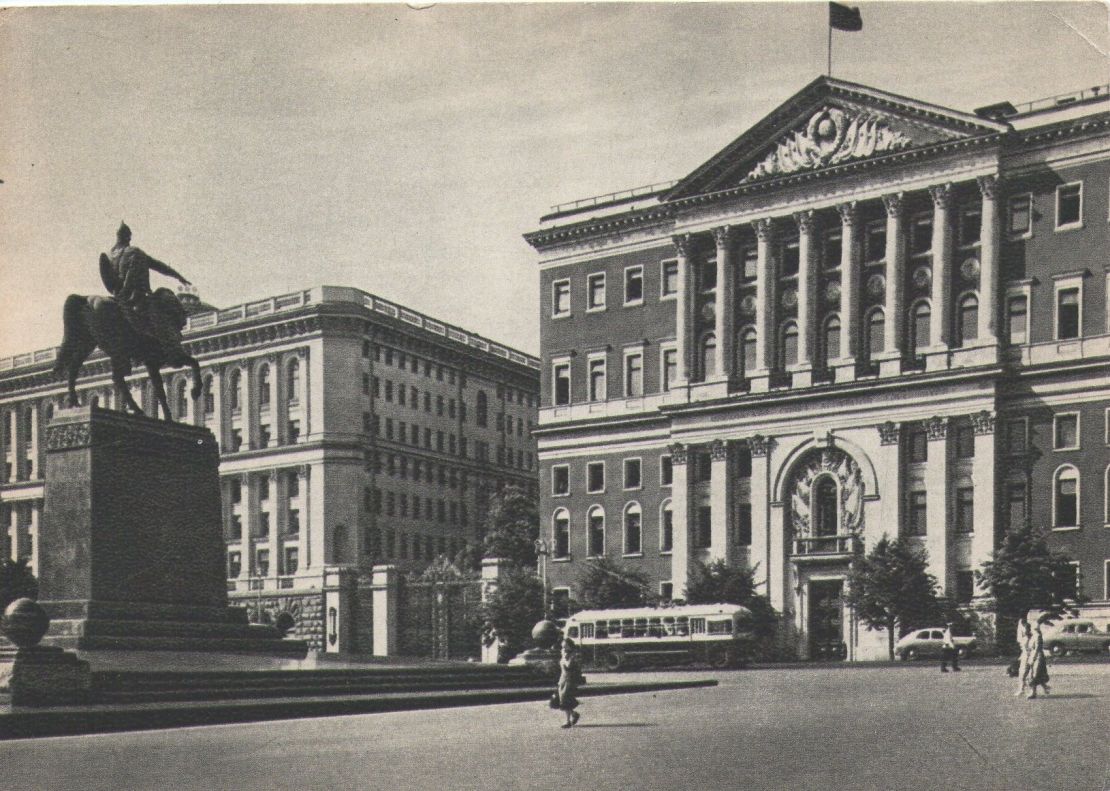

![In<a target="_blank" target="_blank"> an article for the Calvert Journal</a>, Hatherley explains the use of postcards: "If the [books] showed these as mundane places in the 21st century, then the postcards show a publicity image, but publicity that is frequently so odd and jarring that it can be hard to imagine how these photographs were intended as a form of architectural and political PR."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/150826173957-owen-hatherley-post-cards-communism-28.jpg?q=w_2090,h_1083,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)