Story highlights

Architecturally stunning private art museums are booming in China

As China's billionaires mature, and their art investments grow, they are seeking unique ways to leverage their collections

But is it a desire to share culture -- or vanity -- that's driving the projects?

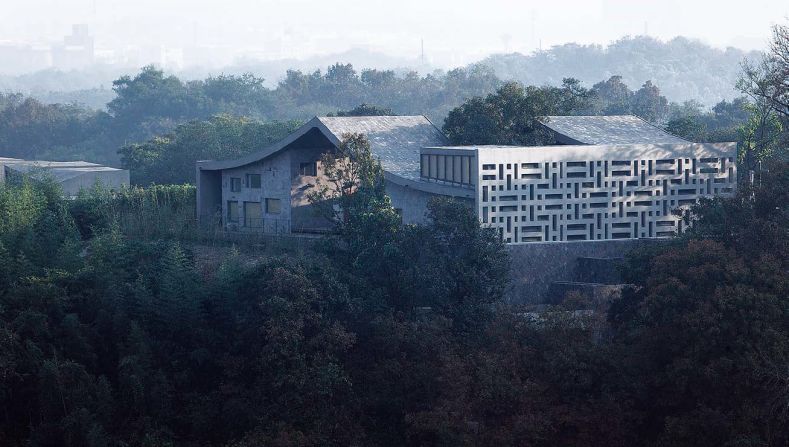

Whether stunning collectives of 20 plus buildings, like the Nanjing Sifang Art Park, or singular architectural marvels, such as the Long Museum West Bund, Shanghai, the construction of private art museums is booming in China.

Driven by the expanding number of Chinese billionaire art investors hoping to leave a cultural legacy, government and municipal policy, and the financial and security disincentives that hinder donation of private art to public facilities, scores of spectacular new museums are being built each year at the cost of hundreds of millions of dollars.

But with architecturally beautiful buildings in remote provincial outskirts containing few – if any – significant artworks, questions are being raised about the breadth of content and curatorial guidance that many of these museums have access to, as well as the motivations behind their construction.

“In many cases architecture comes first and art comes second,” says Jeffrey Johnson, architect and director of Columbia University’s China Megacities Lab.

READ: Inside China’s largest contemporary art collection

Cultural catch-up

The number of museums being built in China by both the government and private individuals has exploded in in recent years, from 2,601 in 2009 to 4,164 in 2014, a 60% increase in just five years, according to the China Museums Association.

The growth in private museums has been even more rapid, increasing more than threefold over the same period to 864 in 2014.

China is, however, catching up from a very low base – just 25 museums existed when the Communist Party assumed power in 1949, many of which fell to ruin during the 10-year cultural revolution that began in 1966.

For comparison, the U.S. is home to more than 35,000 museums and related organizations, according to the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services.

And just as America’s so-called “robber barons” such as Frick, Carnegie and Rockerfeller – names now synonymous with art and culture – helped cement some of America’s great museums, China’s newly wealthy businessmen and women are leading their own cultural charge.

READ: China’s aggressive museum growth brings architectural wonders

“In a culture that has been suppressed for so long, when things start opening up, you’re liable to get a sort of burst of energy and momentum. This generation of private collectors in China, the big ones at least, they’ve had a couple of decades to make their fortunes and it’s natural they’re now spending it on artists and art collections,” says Aric Chen, the curator for design and architecture at Hong Kong’s M+ Museum.

Architectural motivations

“Buy art, build a museum, put your name on it, let people in for free. That’s as close as you can get to immortality,” British artist Damien Hirst once famously said.

Yet, in China, the motivations for founding a museum are more complex.

One significant incentive has been government policy. China’s parliament, the National People’s Congress, has named museum growth as a goal in both of its five-year plans since 2010. Private and industry-based art collectors often receive favorable government real estate deals for their museums, say Johnson and Chen.

Christoph Noe, director of art market research group Larry’s List, says that although some Chinese museum founders are driven by vanity, many are motivated by a desire to share their newly acquired culture with the masses.

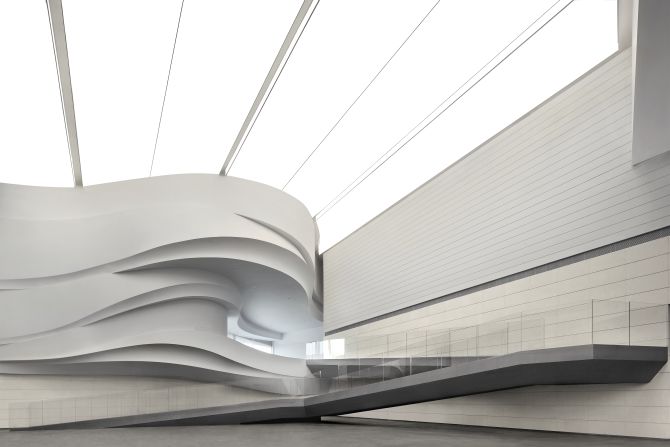

“Nothing is so simple in this world, it’s always a mix,” he says, citing Liu Yiqian’s Long Museum – which occupies two sites in Shanghai, with a third under construction in Chongqing – and the Rockbund Museum, in Shanghai, as two examples of privately funded museums that are thoughtfully meeting their stated intention to bring international culture to the Chinese public.

READ: World’s wealthiest are stashing their cash in art

Johnson says because China lacks the philanthropic culture that exists in the U.S. and Europe, art collectors there don’t receive financial incentives such as tax deductions to donate their collections to public galleries.

He adds that many collectors would also rather build their own museums than donate because of a “real and perceived” notion that public museums don’t have the security or climate control technology to protect the art.

“And the more you are able to control and show your own collection the more opportunity [there is] for that collection to gain in value, so you are also controlling that market with your own collection,” Johnson says.

Both Johnson and Chen also cited the greater curatorial freedom of a private museum in China as a contributing factor.

Motivations aside, Noe says museum founders often lack understanding of what is involved in running an art museum, such as staffing issues, the storage and transport of art, and curation and program planning.

“I think the problem is not so much architecture coming before curation, it’s not enough resources, attention and, frankly, respect given to curation,” says Chen.

READ: Future Chinese Skylines could look more uniform

A good thing for everyone

For all the criticism China’s museum boom has attracted, there is no denying the uniquely stunning architectural creations it has spawned.

“China’s private art museums is everyone’s favorite pi?ata, for all of the obvious reasons, but on balance I would have to think it has been a good thing that has given China’s young architects lot of opportunities,” says Seng Kuan, an architectural historian with the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St Louis.

Chen agreed: “A lot of these projects are still learning, so in some ways we’re all watching as they learn.”

“And I think rather than criticize, it’s much more productive to engage with them.”

CNN’s Shen Lu and Anna Kook contributed to this report.