In Luo Wenyou’s cavernous, hangar-like exhibition building in Beijing’s northern Huairou district, the scents of history and engine oil are dovetailed. Luo owns around 200 vehicles, ranging from a jet black stretch limo made for Mao Zedong to an enormous red fire truck. Last month, his obsession with vintage cars – an esoteric interest in China – was featured in a mini documentary, aptly named “Driven.”

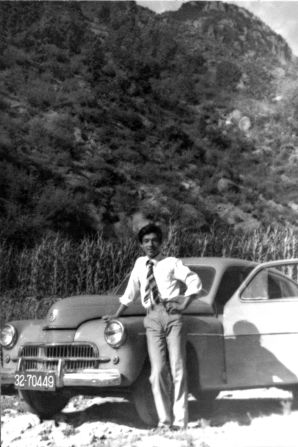

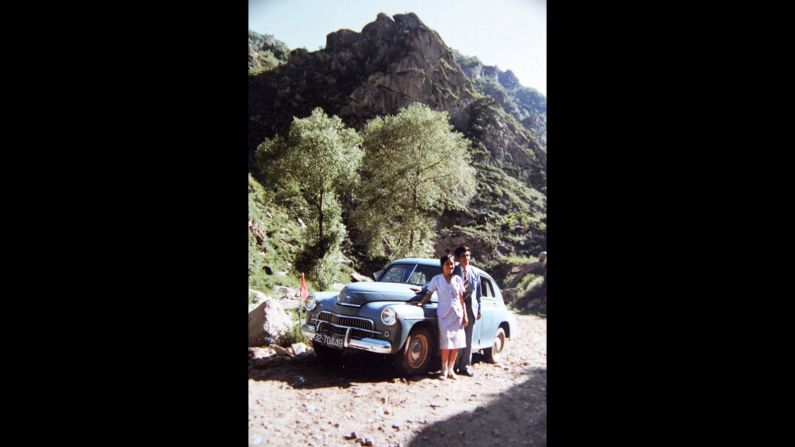

Luo’s collection began in 1979, when he first became what was a rarity in China at the time: a private car owner. He bought a blue Polish Warszawa car for 5,000 Yuan ($725). (Production for Warszawas began in the 1950s).

“I changed my white gloves every day and wore sunglasses when I was driving,” says Luo, sitting in the back of a 1966 limo car made by the brand Hongqi. “Even in the winter I would lower my window so people could see me.

“It was so rare to see a car on the roads and there were no traffic lights, just police officers giving signals.”

Driving government cars

Luo had worked as a driver for government officials, and would later run his own businesses, including an auto repair shop, a travel company, and a go-kart track. But after competing in the Louis Vuitton Classic China Run rally in 1998, he sold his businesses and dedicated his resources to building his car collection, eventually opening the Beijing Classic Car Museum in 2009.

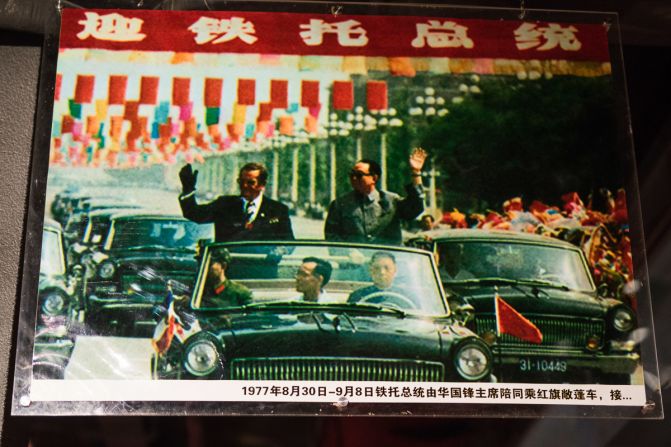

His government connections gave him “guanxi” – social clout – helping him secure rare cars. His collection now acts as an intriguing showcase of Chinese car design, dating back to a time when cars were the preserve of the elite.

“People were in awe of drivers,” says Luo of the period following the end of China’s Cultural Revolution in 1976, when the country was beginning to open up to the wider world. “Only government officials and military leaders used them, but I managed to buy an imported car.”

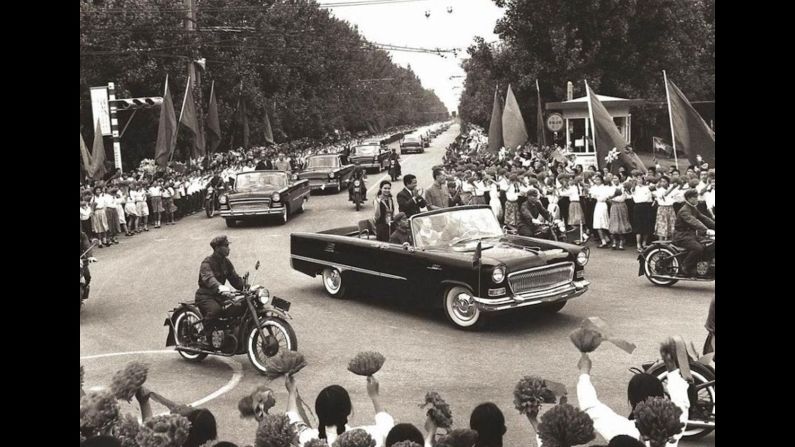

The highlight of Luo’s collection is his cache of Hongqis: broad, sleek black vehicles that were made exclusively for high-ranking government officials. Luo’s stretch Hongqi was made by the firm as a gift for Mao Zedong in 1976, but the chairman died before he could receive it.

The car was kitted out with a telephone, an ice box, air conditioning and leather chairs.

“Back then, there was a culture in which everything was exaggerated to an unbelievable level,” Luo says. “It was a time when a steel factory boss would say their place could produce thousands of tons of steel, and produce fake reports to please the government. The car technicians were excited, and wanted to produce the longest car as a gift for Mao.”

Mao’s influence can be felt through much of the collection. Luo explains that a red Dongfeng car only has Chinese characters on its bonnet because Mao couldn’t read the original pinyin lettering.

The stocky 1945 ZIS car with a shattered window pane was used by Liu Shaoqi, President of China from 1958 to 1968, who was accused of being a traitor during Mao’s Cultural Revolution purge.

“When the Red Guards saw his car, they would throw stones at it to express their anger,” Luo says. “It was a time when people believed that they had to ruin the old world to create a new one.”

A depiction of Mao, his right hand held aloft, is on the wall behind a red-and-white 1950s Dongfanghong (the name literally translates to “the East is red”).

Luo says only a few dozen of them were made because, in the late 1950s, Beijing’s mayor deemed them too bourgeois and western looking, and halted their production.

A historic rally

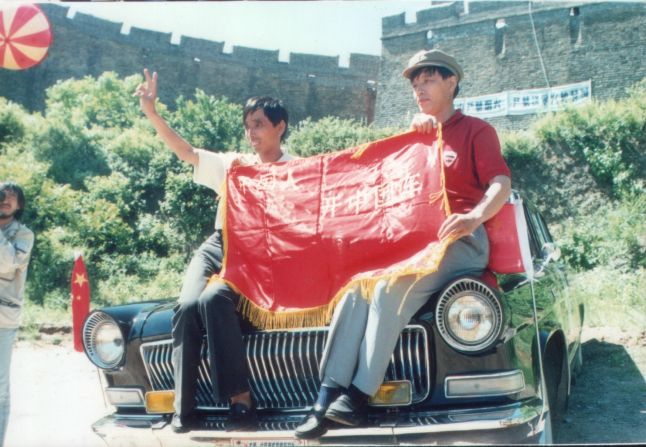

Perhaps the most significant car for Luo, though, is his Hongqi 770. Made in the late 1970s, the car used to belong to Nie Rongzhen, a People’s Liberation Army marshal. Luo drove it on the 808 miles long (1,300 km) Louis Vuitton Classic China Run rally from Chinese city Dalian to Beijing.

Although the rally took place in China, Luo says he was the only Chinese driver to take part in it, making him something of a local celebrity to onlookers.

“I was penalized by the rally officials because my car was surrounded by so many people in Dalian,” he says. “I remember a grandpa holding his granddaughter, then when I drove by, he was so excited he started clapping and dropped her.”

Today, China is the biggest car market in the world, and vehicles are no longer strictly the domain of the elite.

Luo’s museum is a strong reminder of the immense change that has occurred in the country over the past 40 years.

But is there a car he’s still desperate to add to his collection? “I do really want a British steam car,” he says. “I think I have most of the Chinese ones already.”