Editor’s Note: Helen Jennings is the editorial director of Nataal Media, an editorial platform celebrating African creativity.

Mali’s golden age of 20th century studio photography is often focused solely on the work of Seydou Ke?ta and Malick Sidibé, whose evocative black-and-white images have become sought after in the art world. But this special time in the West African country’s history, just before and after it gained independence from France in 1960, gave rise to many other photographers equally deserving of contemporary attention.

Enter Black Shade Projects. The itinerant exhibition platform celebrating African photography, with an emphasis on Mali’s rich archive, was founded by Moroccan art consultant Myriem Baadi last year to grant visibility to otherwise unknown artists and illustrate the nuances of Africa’s photographic lineage.

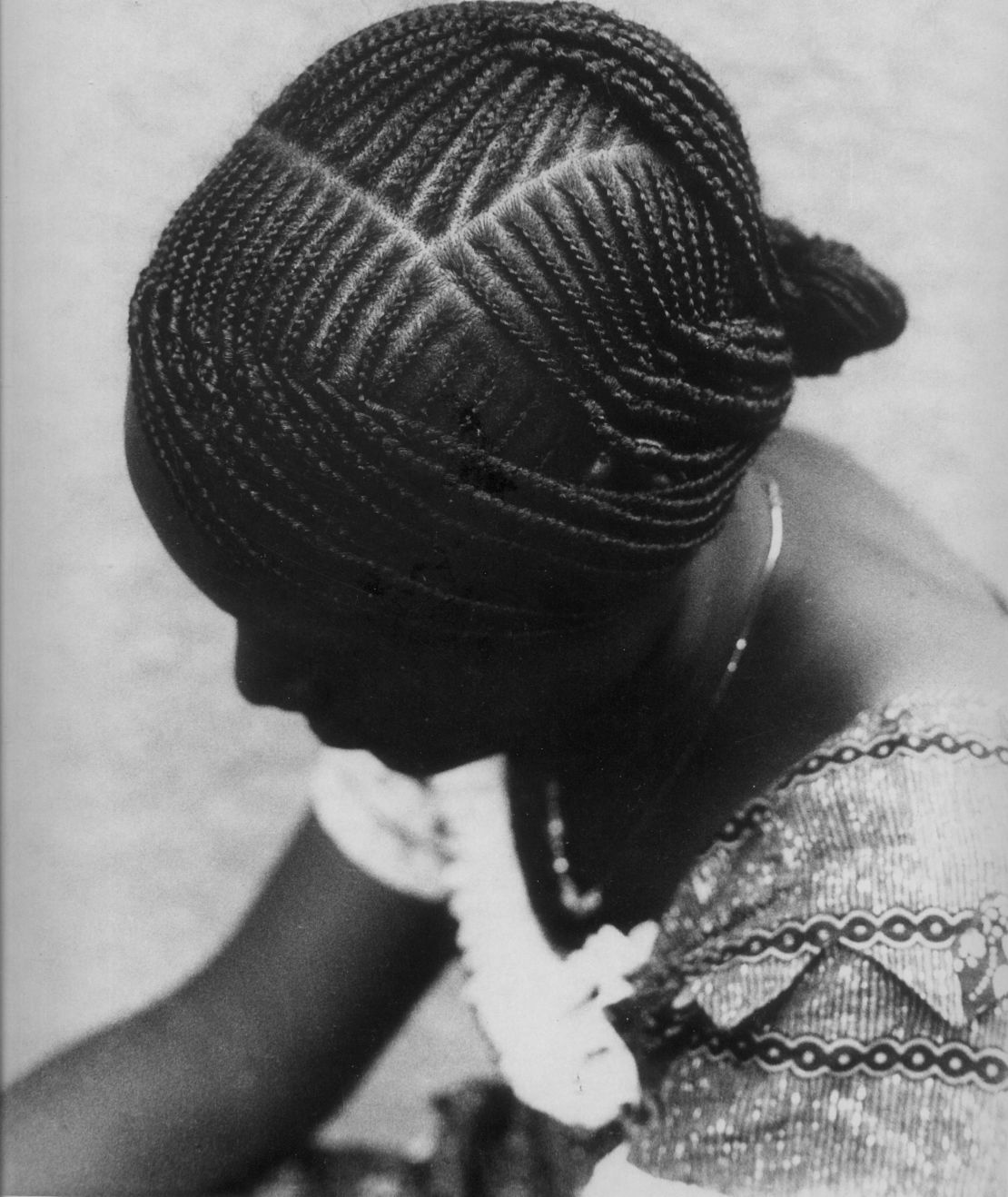

As founder of Nataal Media, an editorial platform celebrating African creativity, I’ve been keenly following the progress of Black Shade Projects since it launched in London last fall with an exhibition of works by Youssouf Sogodogo. This Malian photographer was born in 1955 and went into photography in the 1980s. He’s currently director of the influential Cadre de promotion pour la formation en photographie (CFP) in the Malian capital, Bamako, and has exhibited widely, although not in the past decade. Black Shade Projects presented his series “Tresses du Mali,” which reveals the intricate hairstyles of the country’s women. The timeless quality and universal appeal of the work has acted as the perfect jump-off point for Baadi’s platform.

“Black Shade Projects intends to present Malian photography beyond that of the notable names, not only by preserving the archives of these veterans, but by encouraging an extended conversation with the ambition to widen and diversify art collections,” she said in an interview for Nataal at the time of the launch. “It recounts the multifaceted stories of Africa through a more authentic narrative.”

Black Shade Projects’ second show, “Her Eyes, They Never Lie,” recently concluded at the AFR?Eculture African salon during Marrakech’s unofficial art week in late February. This time, two photographers were on view.

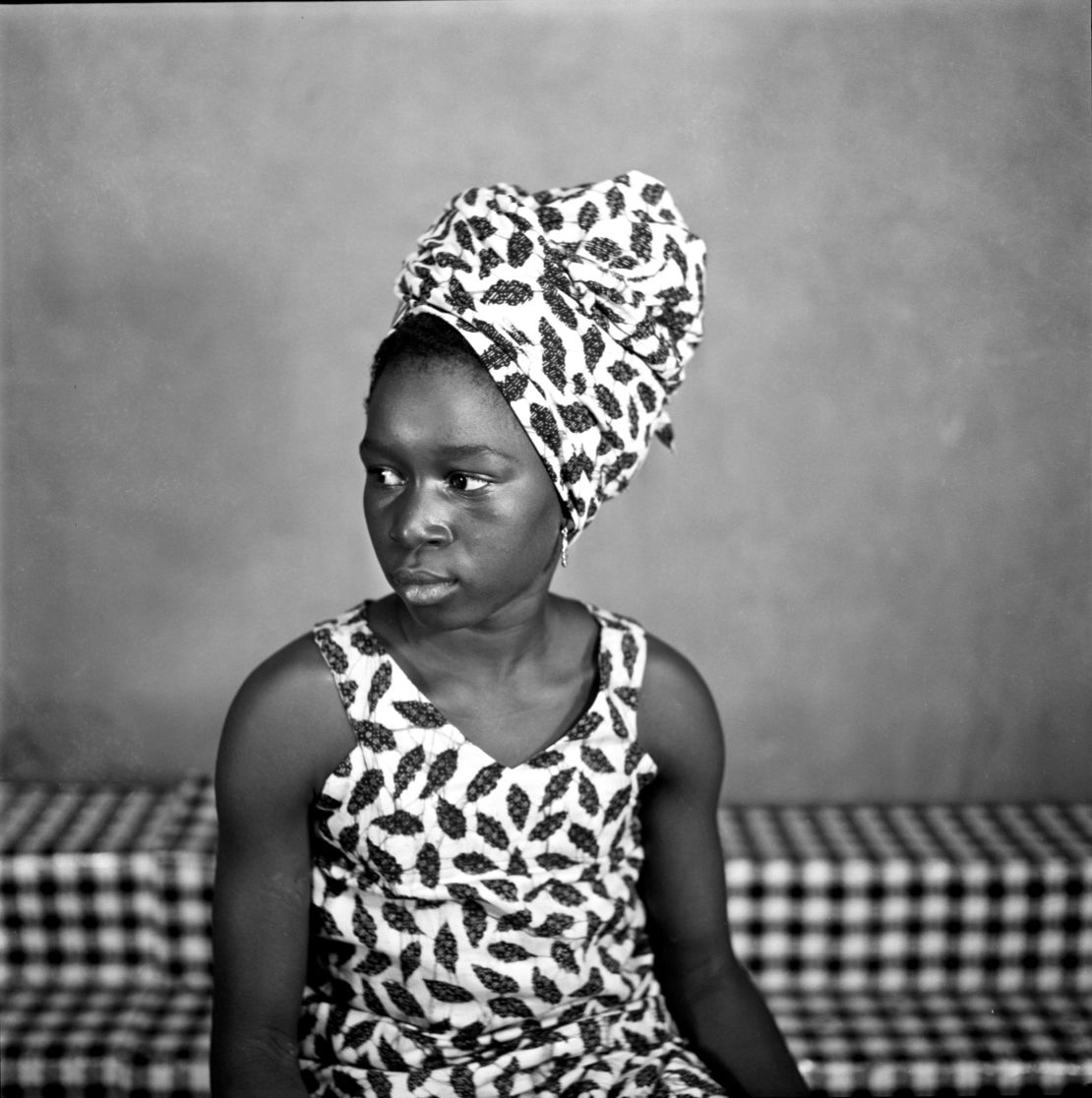

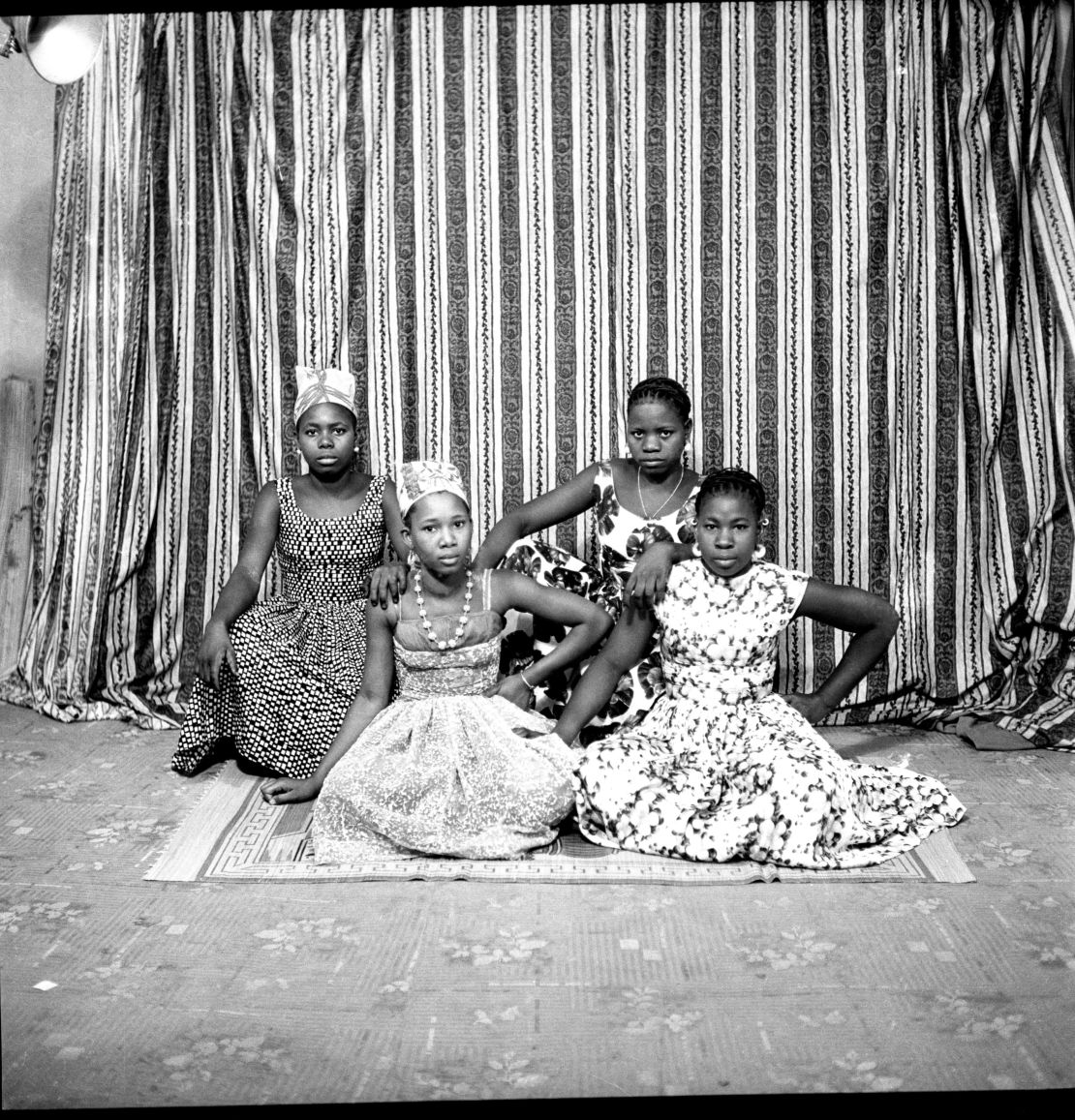

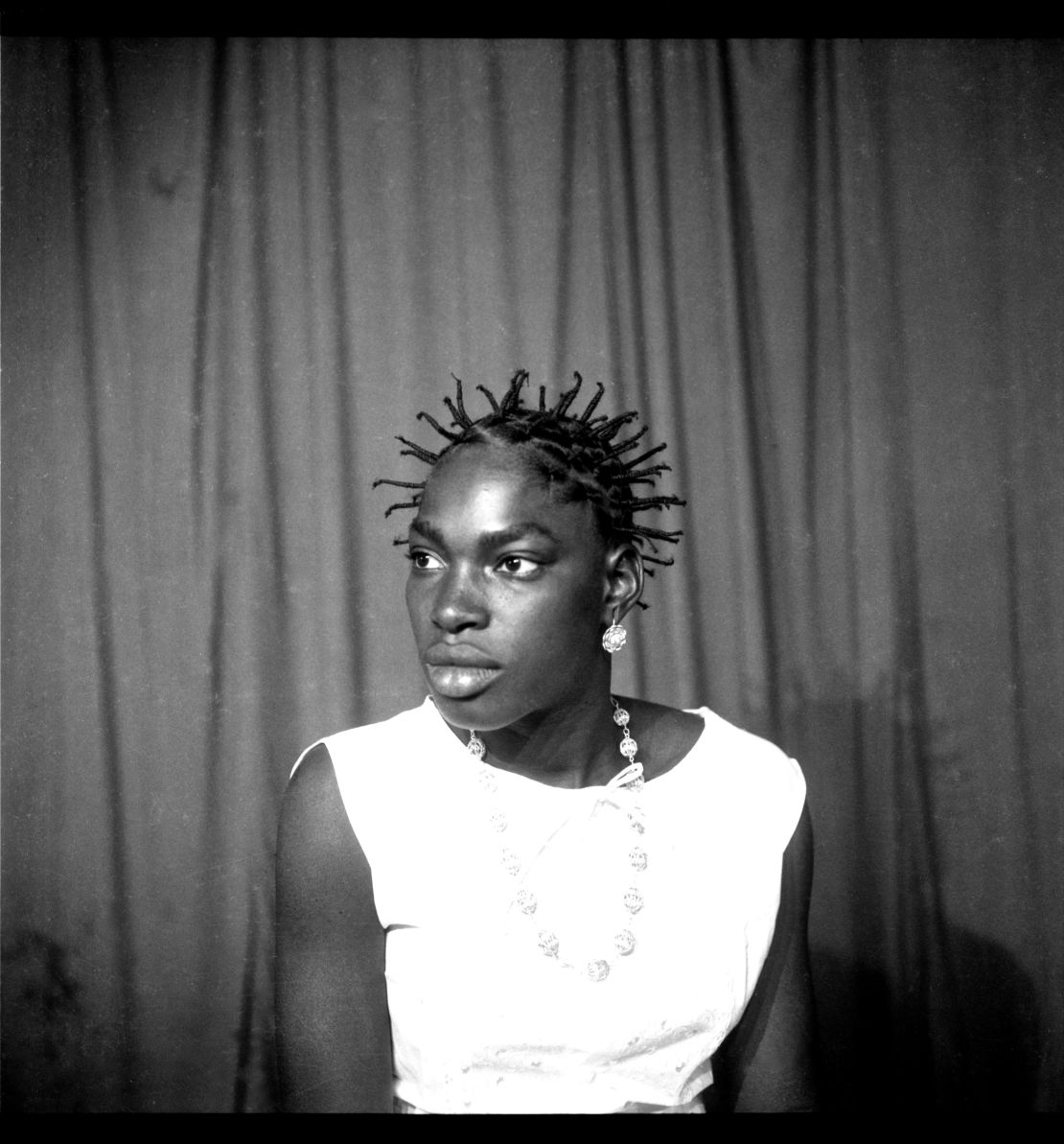

Abdourahmane Sakaly, who hailed from Senegal and moved to Bamako in 1946, became one of the city’s most renowned photographers of the 1960s. Adama Kouyaté grew up in the village of Bougouni in Mali, apprenticed under then well-known photographer Bakary Doumbia in Bamako, and opened studios in towns across Mali and in Bouaké, C?te d’Ivoire. (He passed away aged 92 just days before the exhibition, which marked the first international showing of these specific works.)

“Her Eyes, They Never Lie” focused on these artists’ empathic portraits of female sitters, taken during a time of hope, modernity, and both social and cultural change. Each image is an arranged scene in which women – young and old, family and friends – appear at ease, alluring and confident. Sometimes mysterious, other times strong, they project agency and exude elegance.

“It’s a show about women. But more specifically it’s about the gaze of these women – how they are allowing us to look at them, and are looking back at us,” Baadi explained in Marrakech. “It’s not about the body, or what they look like. Their intention is felt through their gaze. I was keen to represent these artists who are key figures in this niche photography movement and to use their photographs to convey a deeper, more layered narrative. We ask, ‘Who are these women?’”

Lisa Anderson, founder of the platform Black British Art, who curated the show, explained further: “These photographs illuminate the grace and creativity of African women during an era of post-colonial independence in Mali and the African diaspora,” she wrote in an email. “The women of these portraits chose to have them taken to celebrate their individual expression of style, often fusing traditional fashion with Western elements.

“These empowered moments were used as methods of escape and freedom,” she continued. “We’ll never know the circumstances that led them to the studio, but through this exhibition we’ve been able to honor these photographs as cultural treasures.”

Black Shade Projects has also invited textile and performance artist Enam Gbewonyo, who is founder of the Black British Female Artist collective, and painter and performance artist Adelaide Damoah to respond to the archives of artists they’ve exhibited through their own work. This creative dialogue adds further relevance and meaning for new audiences.

As Baadi prepares for future exhibitions, she hopes the pioneers she promotes will fuel new photography on the continent and beyond.

“Their expansive catalogs and artistic innovation paved the way for more diverse cultural practices, which will continue to resonate and inspire future generations,” she said.

Top image: “On est ensemble (We are Together)” (1967) by Adama Kouyaté