Appreciating cultural heritage and using it to imagine a better future: that’s one of the goals of self-taught photographer and visual artist Ade Okelarin.

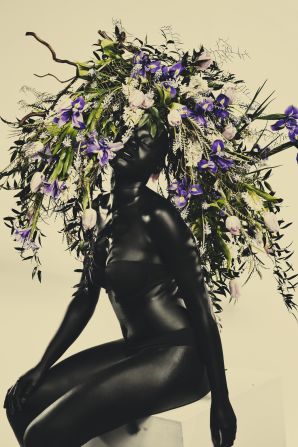

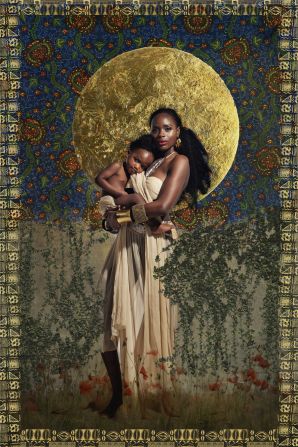

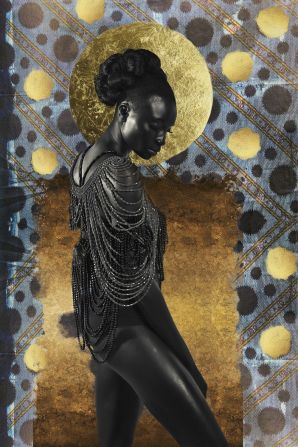

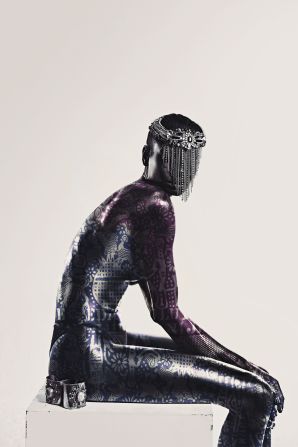

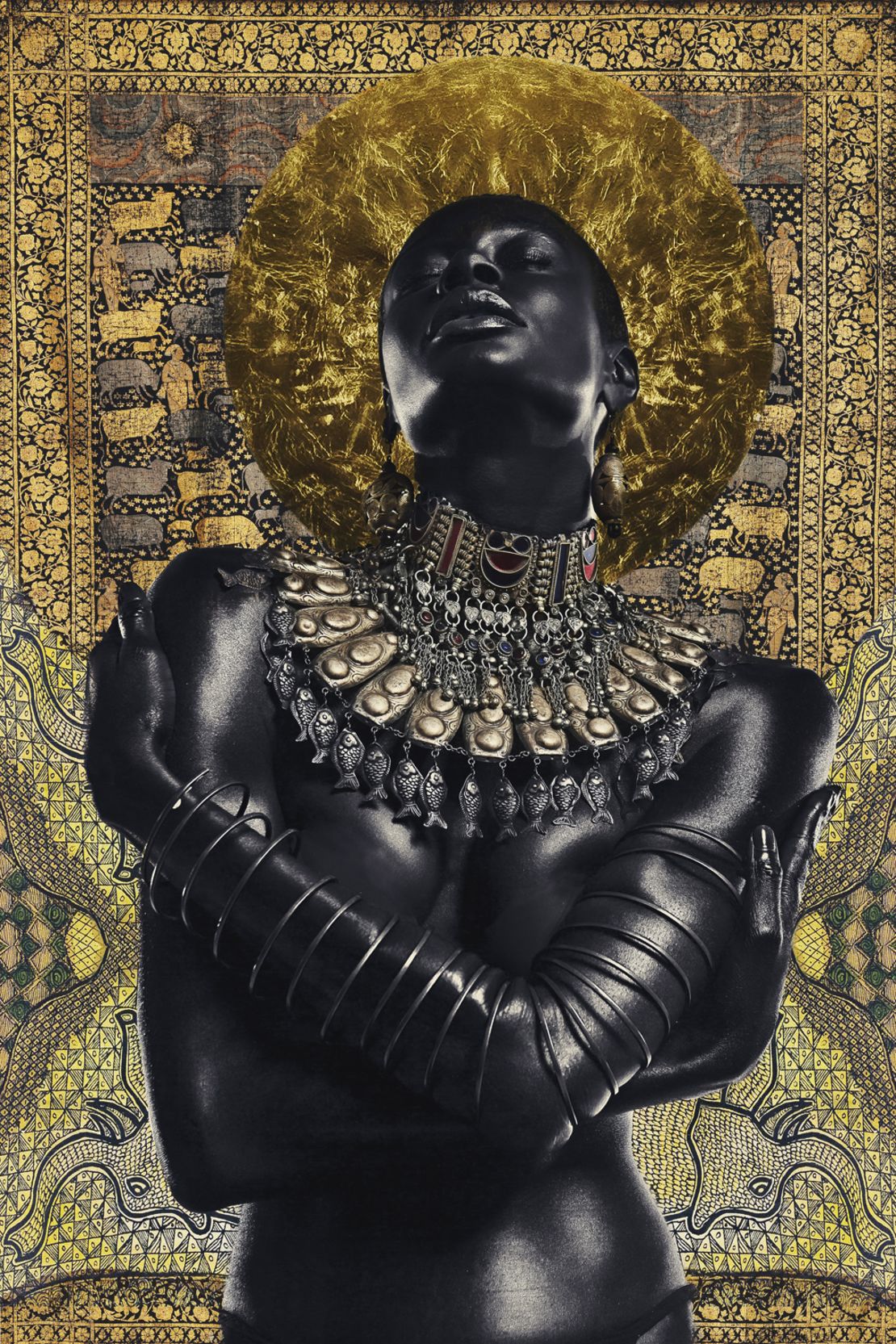

Professionally, he goes by the name of “àsìkò” – the word for “time” or “the moment” in Yoruba, one of the languages in his home country of Nigeria. Drawing on aspects of traditional Yoruba culture has been an important aspect of his creative journey. Through two recent series titled “Guardians” and “Of Myth and Legend,” he explores the iconography of Yoruba deities, or “òrìshàs.”

In Yoruba history, the òrìshàs were sacred beings with divine powers, and the belief in them continues beyond West Africa, having been transmitted by slaves and their descendants in the Caribbean and South America, among other places. But growing up in Nigeria in the 1980s and 1990s, where mainstream education around indigenous beliefs was not common, Okelarin says his journey as an artist has been about deconstructing previous knowledge.

“The work is about exploration and understanding the things I was not taught in school,” Okelarin said, “and creating a space for me to understand heritage and creating something with legacy.”

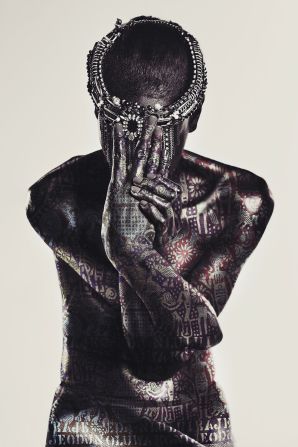

His portraits and images of òrìshàs combine traditional photography with artificial intelligence (AI), digital editing techniques and collaging, and are Okelarin’s way of drawing connections between various global mythologies, through which, he says, we are all linked in our deep-rooted stories.

While researching the projects, he noticed similarities between elements of Yoruba and Western mythology, such as the Yoruba deity Sango and Norse god Thor, both of whom are deities of thunder and lightning, and the òrìshà Olokun, who represents the sea, like her Greek counterpart Poseidon.

The premise of his work, he says, is “looking back to look forward” to know where Africans are from as a society and help carve a future “shaped not by Westernization, but a grounding of cultural ideology and aesthetics.”

Okelarin moved to the UK in 1995 and says his research into his own culture changed his frame of reference from that of a Western gaze to one that celebrates a “beautiful different point of view” and helped him understand his heritage.

“In the world of increasing globalization, it is important to maintain a sense of identity that informs better societal structures,” Okelarin said. “Westernization is not the answer to advancement, but we need a blend of who we are and what the world offers or we will lose what makes us ‘us.’” Creating and sharing these images using modern technology and techniques is one way to show that “our stories matter” he adds.

Raising awareness

Despite having had an affinity for art and photography for as long as he can remember – growing up in Nigeria surrounded by African art his father collected – Okelarin studied chemistry and worked in the pharmaceutical industry as a data architect, due in part, he says, to “Nigerian parents who didn’t want (him) to be a starving artist.” But a shift in mindset over time prompted him to focus full-time on photography by 2015.

Raising awareness about socio-political issues that affect his community and society is another of his roles as an artist, says Okelarin. He says his journey, culture and experiences as a Yoruba man living in the UK are the lifeblood of his work, which has covered topics including female genital mutilation, masculinity, mysticism, identity, and race.

His mythological imagery, as well as other projects, such as the 2020 series “She is Adorned,” utilize the concept of layering, with subjects literally adorned in layers of African beads and jewelry. Okelarin also uses digital rendering, layering the photographs with aspects of his cultural heritage, such as fabric and textures. This blending of different processes – conventional photography with AI – has “opened strong imaginative possibilities” for him.

Some of those new possibilities include painting and sculptural work, he says. In 2022, he created a globe artwork for the World Re-imagined project, a British art history education project around the transatlantic slave trade in which over 100 globes were placed across the UK.

His work has exhibited in the UK, Nigeria and the US, and he recently launched his first set of NFTs with the Bridge gallery, a fine art NFT photography gallery.

With work that reaches into the past, and which is ever evolving, Okelarin says he continues to open himself up to the journey to allow for experimentation and growth.

“As I have grown older, I have found the culture I come from has a beauty and a resonance to it,” he said. “Living in the diaspora, now more than ever, my cultural heritage is a big part of my identity and who I am. It is a strength.”