Editor’s Note: This feature is part of CNN Style’s new series Hyphenated, which explores the complex issue of identity among minorities in the United States.

Tshab Her grew up feeling like she lived a double life.

Like many Asian Americans, the 29-year-old Hmong American artist was always switching between two names: an Asian name and her “American” name.

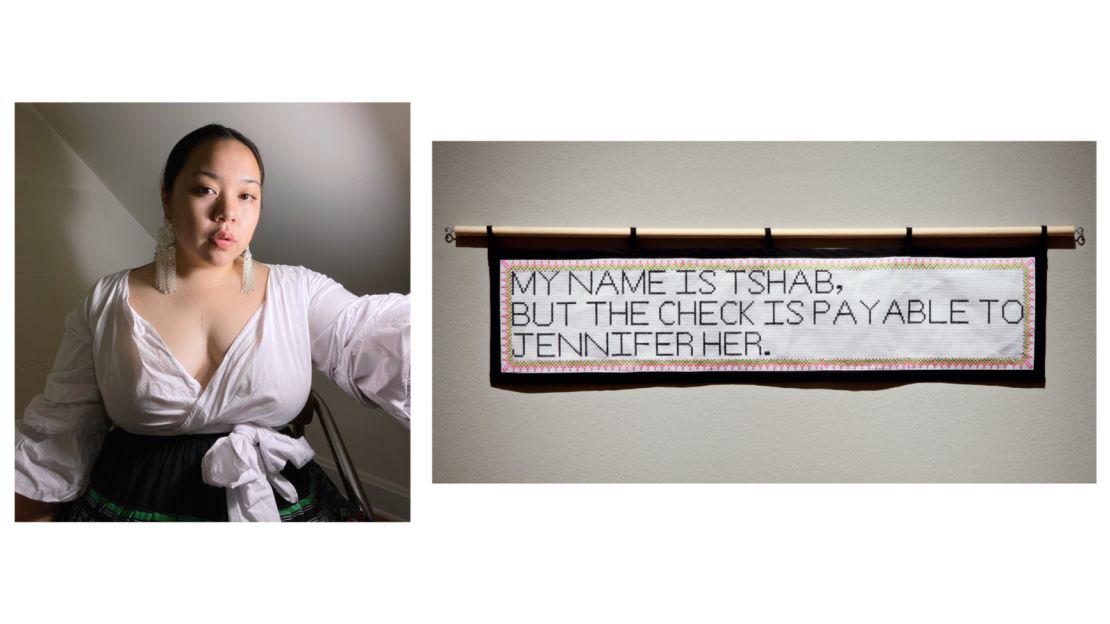

Jennifer, her legal first name, was what teachers and employers called her, and what she used in “White spaces,” she said. But her middle name Tshab, which means “new” in the Hmong language, was what her family and close friends called her within their small community in Aurora, Illinois.

The Hmong ethnic group is spread across China and Southeast Asia, but most Hmong Americans – like Her’s parents – are refugees from Laos who fled during the Vietnam War.

“When I went as Jennifer, I felt like I was playing a role – this White-assimilated, American Dream type,” said Her, now based in Chicago. “Tshab and Jennifer were always at tension with each other … I felt like I was always living a different life as Jennifer, than who I wanted to be as Tshab.”

There’s a long history of Asian Americans using Anglo or anglicized names – whether they adopted new White-sounding names like John or Jennifer, or changed the pronunciation or spelling of their original name to better suit English speakers. The practice was popularized in the 19th century due, in part, to fear in the face of intense racism and xenophobia.

America has since undergone a cultural sea change. The past decade alone has seen surging demand for greater diversity, inclusion and representation. And as the national conversation shifts, many Asian Americans, including high-profile creatives and celebrities, are facing similar personal reckonings with their names.

The list includes comedian and producer Hasan Minhaj, whose interview on the Ellen DeGeneres went viral when he corrected her on the pronunciation of his name; Marvel actress Chloe Bennet, who said she changed her surname from Wang because “Hollywood is racist”; and “Star Wars” actress Kelly Marie Tran, who called her family’s decision to adopt anglicized names “a literal erasure of culture.”

After reflecting on her identity and how she presented herself, Her decided to drop Jennifer and go by Tshab when she started college. It felt empowering, she said – an affirmation of heritage, the Hmong language, and her parents’ journey to the United States in the ’70s and ‘80s.

Unbeknown to many Americans, Hmong soldiers were recruited by the CIA during the Vietnam War. They died by the thousands and were forced to flee when the US withdrew from Vietnam, essentially abandoning the ethnic group. To this day, the Hmong community is among the most marginalized Asian American groups.

For Her, just existing under her Hmong name “creates space in itself” and pays tribute to her roots, she said.

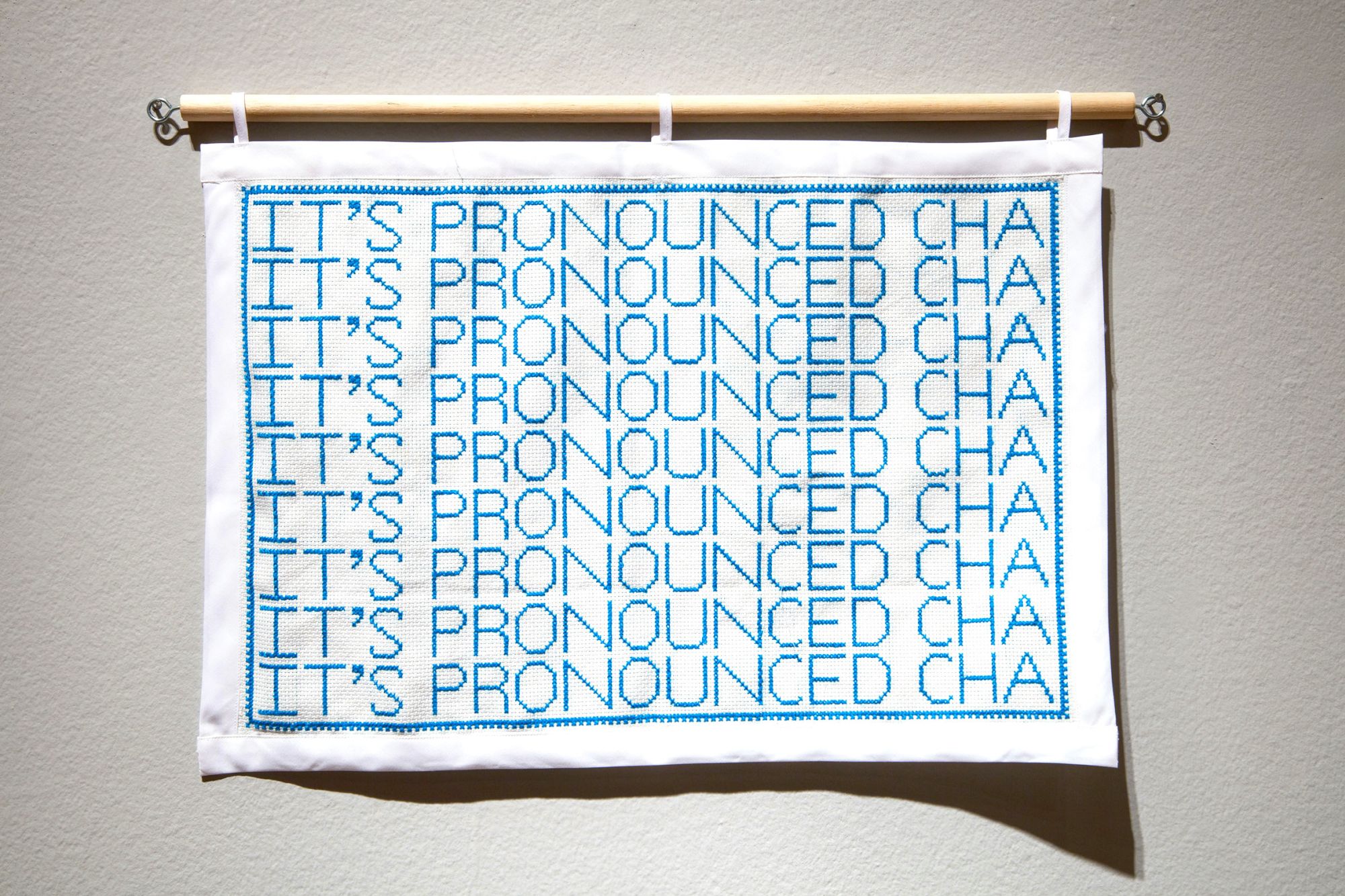

An artist, she also incorporates the journey from one name to another in her work, which celebrates Hmong history and iconography. One embroidery piece reads “It’s pronounced Cha,” while another reads “My name is Tshab, but the check is payable to Jennifer Her.”

A history of violence and assimilation

Asian Americans have been Anglicizing their names since the first major wave of immigrants in the late 1800s and into the 20th century – a practice also common among Jewish and European immigrants, according to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

There are a number of reasons why, with the most basic being convenience. English speakers often had trouble pronouncing or spelling non-English names, and for many immigrants it was just easier to choose a new “American” name. There were financial motivations, too – immigrant business owners may have felt that an anglicized name would better appeal to customers.

Over the years, USCIS archives have recorded countless such name changes from a Russian immigrant named Simhe Kohnovalsky who asked to become Sam Cohn in 1917, to a wartime refugee named Sokly Ny, who fled Cambodia in 1979 during the Khmer Rouge regime and renamed himself Don Bonus in California, inspired by a “bonus pack” of gum.

Any change that might smooth their way to the American Dream was seen (by many immigrants) as a step in the right direction,” wrote Marian Smith, a former USCIS historian, in a 2005 essay, adding: “There were all kinds of reasons, political and practical, to take a new name.”

But this seemingly eager pursuit of the American Dream doesn’t fully capture the dark realities immigrants faced. Asians in the US were often demonized, exploited and discriminated against from the moment they arrived. Assimilation – including the adoption of a new name – was seen a survival tactic.

Early Chinese immigrants were lynched by mobs, and anti-Chinese sentiment was so strong that the US banned all immigration from China between 1882 and 1943. The fearmongering “Yellow Peril” ideology meanwhile depicted East Asians as dangerous invaders. An estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans – the majority of whom were US citizens – were forced into concentration camps during World War II.

An increasing number of Japanese Americans changed their personal names during wartime in order to “prove their patriotism and to reaffirm their American identities,” according to a 1999 paper in Names, a journal dedicated to onomastics (the study of names). “Makoto became Mac, and Isamu shrank to Sam.”

Asians in the 19th and early 20th century were largely portrayed as “strange, but also inferior, dirty, uncivilized,” said Catherine Ceniza Choy, a professor of Asian American and Asian diaspora studies at the University of California, Berkeley. “(Back then) the desire to fit in is also about surviving an overtly racist, hostile society” that targeted “Asian difference.”

In the period 1900 to 1930, about 86% of boys and 93% of girls born to immigrants (of all origins, not just of Asian heritage) had an “American name,” according to US census data analyzed in the journal Labour Economics.

Now, a century later, it’s common for members of the third or fourth generation not to have an Asian name at all.

The cost of sacrificing a name

The nation and its racial tensions have evolved since then – but Asian and non-English names continue to be othered, treated as strange or used as cheap punchlines.

In 2013, for instance, a TV station reporting on a deadly Asiana Airlines plane crash fell for a prank, and announced that the pilots included “Captain Sum Ting Wong” and “Ho Lee Fuk.” In 2016, the governor of Maine joked about a Chinese man named Chiu, pronouncing it with a fake sneeze. In 2020, a professor at Laney College asked a student, Phuc Bui Diem Nguyen, to Anglicize her Vietnamese name “to avoid embarrassment” because Phuc Bui “sounds like an insult in English.” The list goes on.

Asian Americans have continued to proactively adapt their names, many citing ongoing forms of discrimination. Bennet, who started her acting career as Chloe Wang, spoke out about changing her surname on social media after being questioned about it in 2017.

“Changing my last name doesn’t change the fact that my BLOOD is half Chinese, that I lived in China, speak Mandarin or that I was culturally raised both American and Chinese,” she wrote. “It means I had to pay my rent, and Hollywood is racist and wouldn’t cast me with a last name that made them uncomfortable.”

Tran, the “Star Wars” actress, has also spoken publicly about the pain of assimilating. Growing up, she internalized racist narratives “that made my parents deem it necessary to abandon their real names and adopt American ones – Tony and Kay – so it was easier for others to pronounce, a literal erasure of culture that still has me aching to the core,” she wrote in the New York Times, before declaring, “You might know me as Kelly … My real name is Loan.”

Their public testimonies are part of a growing conversation about the potential psychological toll of adapting or compromising your birth name. Names aren’t just an arbitrary collection of letters and sounds; for Asian Americans, who often juggle multiple languages, cultures and socioethnic circles, a name can encompass various elements of identity.

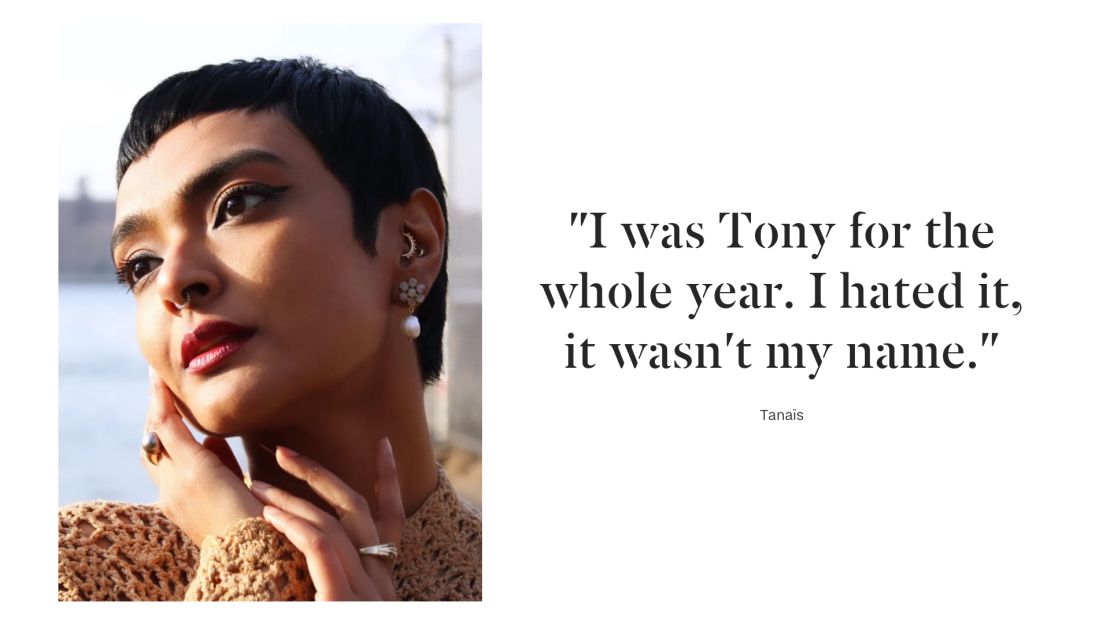

For instance, Tana?s, a Bengali American novelist and owner of a beauty and fragrance brand, was born with the name Tanwi Nandini Islam. Tana?s, 38, uses they and them pronouns.

Their parents, who had immigrated to the US from Bangladesh, chose their birth name carefully; “Tanwi” has various meanings in Sanskrit, including a blade of grass. “Nandini” means daughter, and is another name for the goddess Durga. And “Islam,” which also reflects their family’s Muslim background, means peace. Tana?s, the name they go by today, is the combination of the first two letters of the three names.

“To have a name that holds all these cultural meanings, is very powerful,” they said. “I am all of those things, from my ancestors to where I am now.”

But during childhood, nobody knew how to say “Tanwi,” or put any real effort into learning, they said. Tana?s does not even remember teachers saying their name out loud, with a first grade teacher declaring that “Tanwi” was too hard to pronounce and using Tony instead.

“I was Tony for the whole year. I hated it, it wasn’t my name,” said Tana?s. “I remember being very unhappy – I felt misunderstood. I felt misgendered because it sounded like a boy’s name to me.”

To accidentally bungle someone’s name upon introduction can be an innocent mistake. But to deliberately dismiss their name as too strange or complicated to attempt, like Tana?s’ teacher did, sends the message that “you don’t matter, you don’t belong,” said Choy, the UC Berkeley professor.

“The consistent mispronunciation or misspelling of one’s Asian name – questions and requests for you to simplify or change your name – do take a toll on one’s individual psyche,” she said. “Names reflect your presence, your being, your history. When people constantly do that, they’re not acknowledging you – as a person, as a human being.”

Research has reinforced just how pervasive this problem is. A 2018 survey of Chinese students in the US found that the “adoption of an Anglo name was associated with lower levels of self-esteem, which further predicted lower levels of health and well-being.”

However, the study cautioned that it could be a case of correlation, not causation – for instance, people who already have higher self-esteem could be more reluctant to change their names, and less influenced by stigma.

Another survey of ethnic minority students, conducted by California researchers in 2012, concluded that “many students of color have encountered cultural disrespect within their K-12 education in regards to their names … When a child goes to school and their name is mispronounced or changed, it can negate the thought, care and significance of the name, and thus the identity of the child.”

Minhaj, the comedian and producer, called out Anglo-centric hypocrisy surrounding names during a segment on “The Ellen DeGeneres Show,” where he corrected the host on the pronunciation of his name.

“When I first started doing comedy, people were like, ‘You should change your name,’” he went on to explain. “And I’m like, I’m not going to change my name. If you can pronounce Ansel Elgort, you can pronounce Hasan Minhaj.”

A reclamation of heritage

There are, however, signs of gradual change.

The number of people adopting new names fell in the late 20th century, said Smith, the former USCIS historian. This was partly due to the emergence of automated systems, like those used to register drivers’ licenses, that are designed for just one legal name. But social change was likely a bigger factor, she said.

“While the economic, legal, systemic pressure to maintain one name grew, social pressure to Americanize names also lessened as more Americans embraced cultural pluralism or multiculturalist views,” Smith said in an email.

We see this cultural shift in how people respond to instances of discrimination or xenophobia. Things that previously may have flown under the radar are now being called out, loudly and publicly.

For instance, the writer Jeanne Phillips sparked intense outrage in 2018 when she encouraged parents not to give their children “foreign names” on her syndicated column Dear Abby, adding that they can sound “grating in English.” Furious parents and minority commentators argued she was perpetuating racist and assimilationist narratives, in a controversy that made national headlines.

The Laney College professor who asked a Vietnamese student to Anglicize her name also faced widespread backlash and was placed on administrative leave.

In March, the Atlanta spa shootings that killed eight people – six of whom were Asian women – reignited similar conversations. After several news outlets released abridged or inaccurate versions of the victims’ names, furious and grieving Asian Americans spoke out online about the racist treatment of their names amid a wave of anti-Asian violence and hate crimes.

“PLEASE STOP BUTCHERING THE VICTIMS’ NAMES,” tweeted Michelle Kim, co-founder of Awaken, an organization that runs diversity and inclusion workshops. “These might be small inconveniences to people. But our names are our IDENTITY. It’s our HERITAGE. It’s what we have left that remind us WHO WE ARE. WHERE WE COME FROM.”

These recent controversies are a reminder of how much work is left to be done – but also show that minority groups, and wider society, are redefining the norms of what is acceptable and what needs to be held accountable. It reflects an increasingly multicultural context – a shift that has resulted from broader changes around the world like globalization and a reshuffling of power.

Some Asian countries have become major political and economic players in recent decades, and have also wielded influence in the form of soft power. Bollywood, K-pop, anime and other aspects of Asian pop culture, for example, have gained legions of fans worldwide. And in the US, immigration policies in the late 20th century have allowed the Asian American population to increase exponentially, said Choy.

“That’s just such a different social context to be in, compared to the way it was in the ’50s, ‘60s, ‘70s,” she said, adding that technological advances and globalization mean the “dominance of Anglo-American culture” is now “lessened.”

This new chapter is reflected in the growing demand for greater diversity across nearly every sector: entertainment, politics, food, education and more. And among young Asian Americans, there is also an increasing awareness of what their immigrant parents or grandparents had to give up to survive – a “realization that there is a loss of heritage and culture from the Asian home country,” said Choy.

For some, this realization can spark a desire to get back what was lost. By studying their parents’ or grandparents’ first language, for instance. Others might visit their ancestral homes to reconnect with their culture.

For Her, embracing her Hmong name has become a way to assert her heritage.

“Going as Tshab was an act of resistance,” she said. “I just want to be who I am, and who I am is Tshab, not (Jennifer). That was the start of me resisting this Whiteness of American culture that was forced on me.

“I think, for me, it’s natural for me to feel like I am connected to my parents or my ancestors, going more as Tshab, and not wanting to forget where I come from, where my family (are from) and what the Hmong people have gone through.”

Top image: A piece of embroidery by Hmong American artist Tshab Her.