When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, Taiwanese architect and engineer Arthur Huang wanted to do something to help. As the construction industry across the world ground to a halt, putting many of his projects on hold, Huang turned his attention to solving the urgent need for medical supplies and hospital space.

Based in Taiwan’s capital, Taipei, Huang is the co-founder and CEO of Miniwiz – a company that takes different types of waste and transforms them into over 1,200 materials that can be used for construction, interiors and consumer products.

With the pandemic affecting shipments of conventional materials, Huang found an alternative that’s never in short supply. “We have been building medical parts, medical components and a medical modular ward system all out of local trash,” he says.

The result is the Modular Adaptable Convertible (MAC) ward – the world’s first hospital ward built out of recycled materials, according to Miniwiz. It was designed by the company in partnership with the Fu Jen Catholic University Hospital in Taipei, and may begin to admit patients as early as June.

The walls of the MAC ward are lined with panels made from 90% recycled aluminum, and insulation made from recycled polyester. Cupboard handles and clothes hooks are made from recycled medical waste such as PPE.

A portable version can be built from scratch in 24 hours, Huang says, allowing it to be transported to places with high medical need.

“I think that [the] pandemic forces us to become very innovative to come up with the solutions to adapt to the current situation,” he says.

Taking inspiration from ancient Rome

Huang’s interest in reusing waste has its roots in antiquity. While studying archaeology in Rome in 1999, he noticed something that would send him on a life-long mission to revolutionize recycling: many of the city’s ancient buildings were partly made from trash.

Huang was inspired by the Roman practice of mixing fragments of used terracotta with lime to form a waterproof plaster that was commonly used in building.

The Roman empire used terracotta amphora to transport goods like oil, grain and wine across the Mediterranean. Many of these containers were dumped near ports when their contents were decanted.

“A lot of foundations, aqueducts, infrastructure built in Rome are actually made from cement … from single-use packaging,” Huang says. The idea of taking waste and repurposing it for building would form the foundation of his work for the next 20 years.

Huang has worked on developing ways to turn post-consumer waste, like plastic bottles, as well as post-construction and post-agricultural waste, into materials that have now been used in buildings, restaurants and stores across the world, from Milan to Shanghai.

One material which can be used for ceiling panels is made from waste rice husks mixed with recycled DVDs and LED lenses. Another, made from recycled plastic, electronic waste and automotive waste, is used to make a weather-resistant shading system for buildings.

The Nike Kicks Lounge store in Taipei is full of such innovations. A giant air bubble made from recycled factory waste hangs suspended from the ceiling, acting as both insulation against the sun and a lighting structure. Many of the fixtures, including the cash register counter, have been made from ReGrind – a material Miniwiz developed from ground down soles of Nike shoes and other waste. Chairs in the store are made from the recycled shoes of famous Taiwanese athletes.

“Democratizing” zero-waste technology

Alongside developing new materials, Huang is looking for ways to tackle the environmental challenges posed by the global recycling industry.

Research suggests only about 9% of plastic waste ever produced has been recycled, with much of it ending up in landfill, incinerated or mismanaged, and many developed countries ship their waste elsewhere for processing.

The business of shipping recycling across the world to be processed is a big part of the problem, Huang says, as it increases the risks of contaminating materials, which makes recycling difficult. It also has a bigger carbon footprint than recycling locally.

To help “democratize” its zero-waste technology, Miniwiz shifted its mission to make recycling more accessible to communities around the world to help avoid the practice of exporting waste.

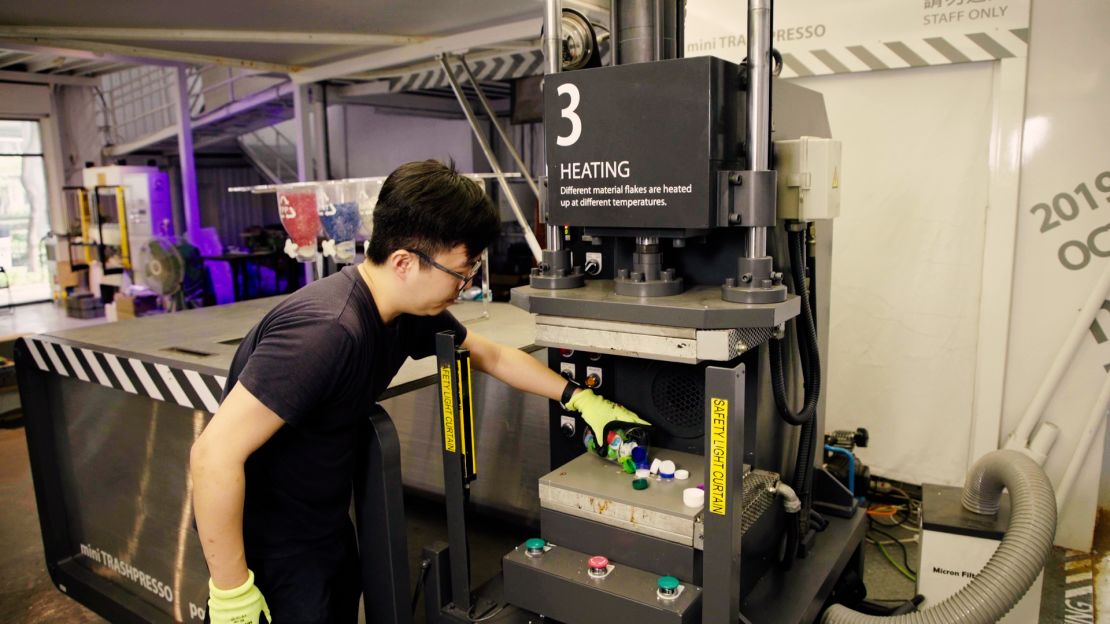

Inspired the Disney movie Wall-E, about a little robot with the ability to detect different kinds of waste in a dystopian world covered in landfills, Huang and his team set about designing a portable, solar-powered recycling machine that could be taken to places where plastic waste is an increasing problem. The Trashpresso was born.

The latest version comes with an AI recycling system that can detect different types of plastic, which the machine can shred and melt into new products such as containers or tiles.

Miniwiz says its Trashpressos have recycled over 203,000 water bottles across 10 cities worldwide. The goal is to develop a fully automated version and to scale up this system to make local recycling facilities that are easily accessible for communities worldwide.

“We don’t need to create new things,” Huang says. “We just need to use our ingenuity, innovations and our good heart and good brain to transform these existing materials into the next generation of products and buildings to power our economy.”

Video by Hazel Pfeifer.