Photography from the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, has received limited exposure in the art world – not least due to the strict limitations imposed by the former authoritarian state.

A new collection of images, first shown at the 2019 Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in the south of France by curator Sonia Voss, shines a light on the works that emerged from the GDR in the last decade before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

“The decade preceding the fall of the wall is a very interesting one for the arts in Germany because there was a new generation that had not witnessed the founding of the GDR,” Voss said in a phone interview.

“These were young people who were very detached from political ideas, but somehow just as tired and furious about the constraints that they were living with, which made them more likely to break the norms or push the limits compared to previous generations.”

In the “Restless Bodies” series, Voss explores how the body was at the center of these artists’ creativity. Photographing one’s own body, Voss explained, was an act of affirmation and resistance in a society that discouraged individuality and was suspicious of the arts. And by photographing others, the artists were able to provide lasting documents of East German realities.

Such was the case with Ute Mahler, one of the artists featured in the exhibition, whose “Living Together” comprises family portraits taken in Leipzig. In the exhibition’s notes, she explains: “I wanted to get a peek behind the fa?ade of the official rhetoric of optimism. I looked for what was real in people’s private lives.”

Similarly, Christiane Eisler’s photos of Leipzig’s punk community offer a glimpse into a private world.

“She followed them everywhere for a quite long time. It was a community that was very strongly under repression from Stasi. These are very melancholic portraits because of the tension between the rage and the despair, which was omnipresent in the GDR,” Voss said.

Fashion photographer Sibylle Bergemann was commissioned by popular magazines, but also captured underground fashion scenes.

“She created a group with young designers who made clothes with whatever they could find, to develop a style that you could not see in stores. They made a lot of illegal shows, which were extremely successful, and Sibylle documented many of them,” Voss explained.

![Manfred Paul, Verena -- Geburt 3, [Verena -- Birth 3], 1977.](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/190628164758-restless-bodies-2019-corp-cat08.jpg?q=w_1110,c_fill)

While Manfred Paul is primarily known for a series of photographs of Berlin’s courtyards, the series focuses on the portraits he shot of his wife as she gave birth to their first son. With their intimacy, they offer a radical contrast to the social discourse seen elsewhere.

![York der Knoefel, from the Schlachthaus series [Slaughterhouse], 1986-1988.](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/190628135751-restless-bodies-2019-corp-cat16.jpg?q=w_1110,c_fill)

Self-taught photographer York der Knoefel spent two years documenting a Berlin slaughterhouse. “He saw it as a metaphor for the human condition and sacrifice for society,” Voss said.

“To go with the portraits, he created an installation made out of zinc-coated plates which formed a labyrinth. He is a typical example of how a young person who did not receive a standard education really pushed the limits of photography.”

![Rudolf Sch?fer, Der ewige Schlaf -- visages de morts [The Eternal Sleep -- Faces of the dead], 1981.](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/190628164638-restless-bodies-2019-corp-cat09.jpg?q=w_1110,c_fill)

The striking portraits taken by artist Rudolf Sch?fer are from a morgue at the Charité Hospital in East Berlin.

“I put this series in in the same section of the exhibition as other portraits, because for me it was like a quest for the ultimate essence of an individual. When you’re a corpse you’re not a social thing anymore, you’re not a part of society, you’re just yourself down to the essence of your being,” said Voss.

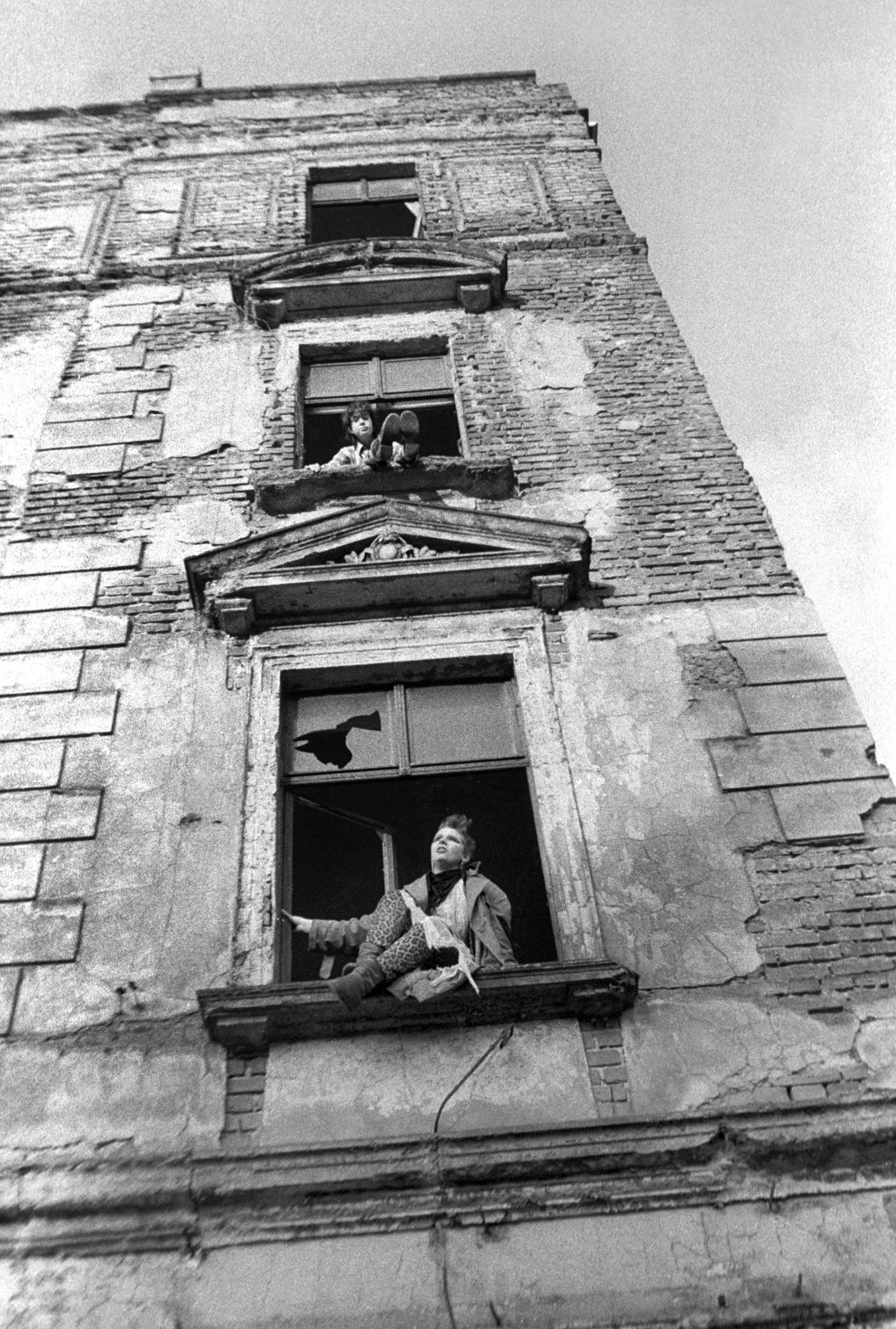

Top image: Gundula Schulze Eldowy, Berlin, 1987, from the “Berlin on a dog’s night” series.