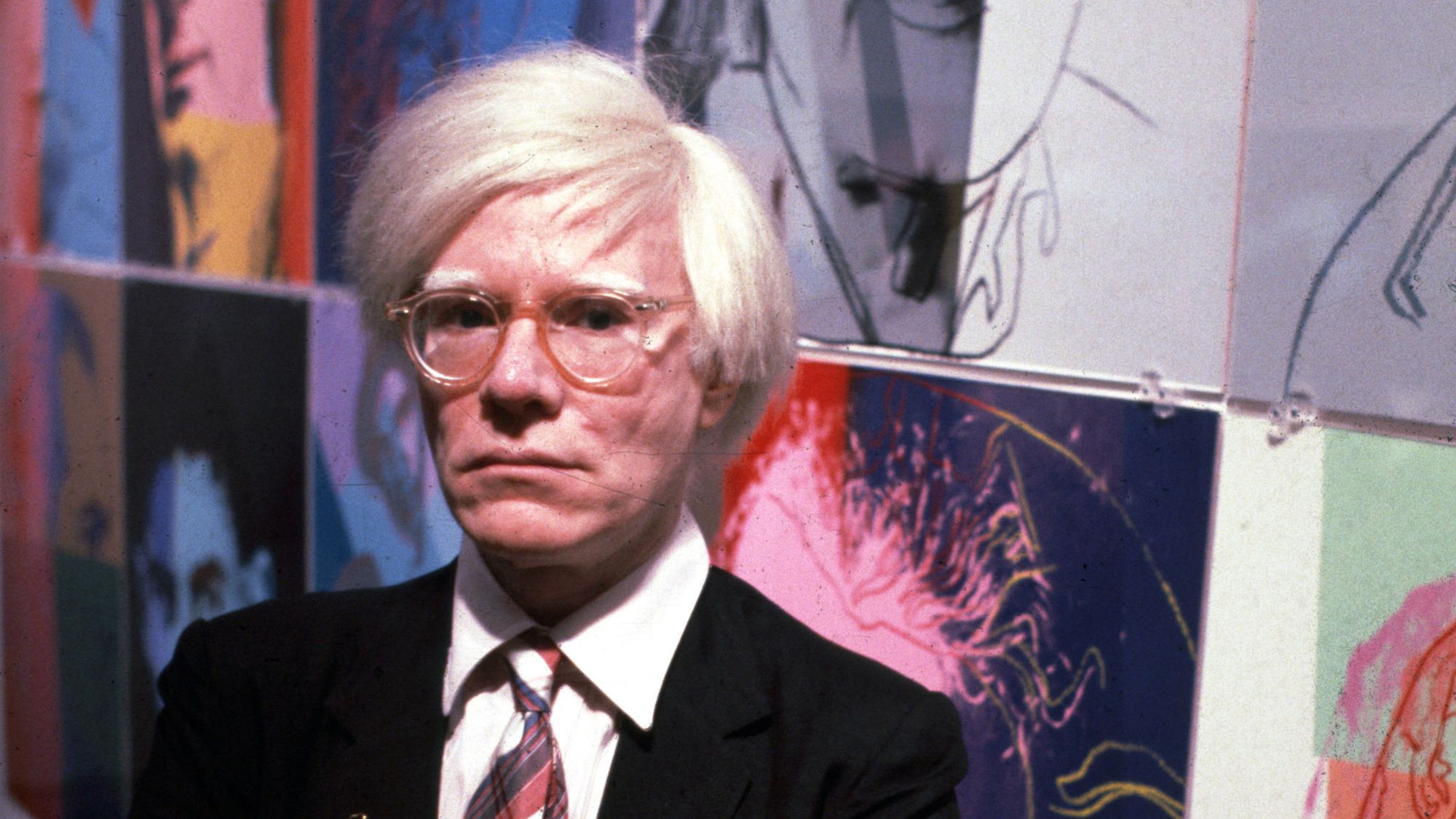

More than three decades after his death, Andy Warhol continues to fascinate and confound art historians, scholars and buyers. He produced some of the 20th century’s best-known images, yet the meaning of his work is still subject to fierce debate; he lived in the public eye, yet he remains an enigma.

With this week marking the opening of a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, we asked three experts, including the show’s curator, to reflect on Warhol’s relevance today and the questions that remain unanswered.

Donna?De Salvo, curator

Donna?De Salvo is the deputy director for international initiatives at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the curator of its new exhibition “Andy Warhol – From A to B and Back Again.”

Warhol reflected a time in the US that we now see differently. But when you look at the obsession with celebrity that emerged in the 1960s, and fast-forward to now – when the obsession is on steroids – you realize that he saw it all very early on. He was prescient in anticipating the construction of personality and the way that brands and personalities would blur.

We’re in the age of the Kardashians. We’re in a place where we have a president who was once a reality TV star. An exhibition like this is usually scheduled four or five years in advance, so there is this interesting coincidence about the climate of today and how it intersects with this show.

Warhol was, to a degree, a painter of his time. But there was also an understanding of where things were headed. In his book “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol” (from which the exhibition takes its name) you see ideas that are still highly relevant: his observations on the rich, on sex, on working.

There’s been a lot of new scholarship since 1989 (the last time a US institution organized a Warhol retrospective) and there’s a whole new generation to engage with – one that was not even born at the time. I’m really eager to find out the response of younger audiences.

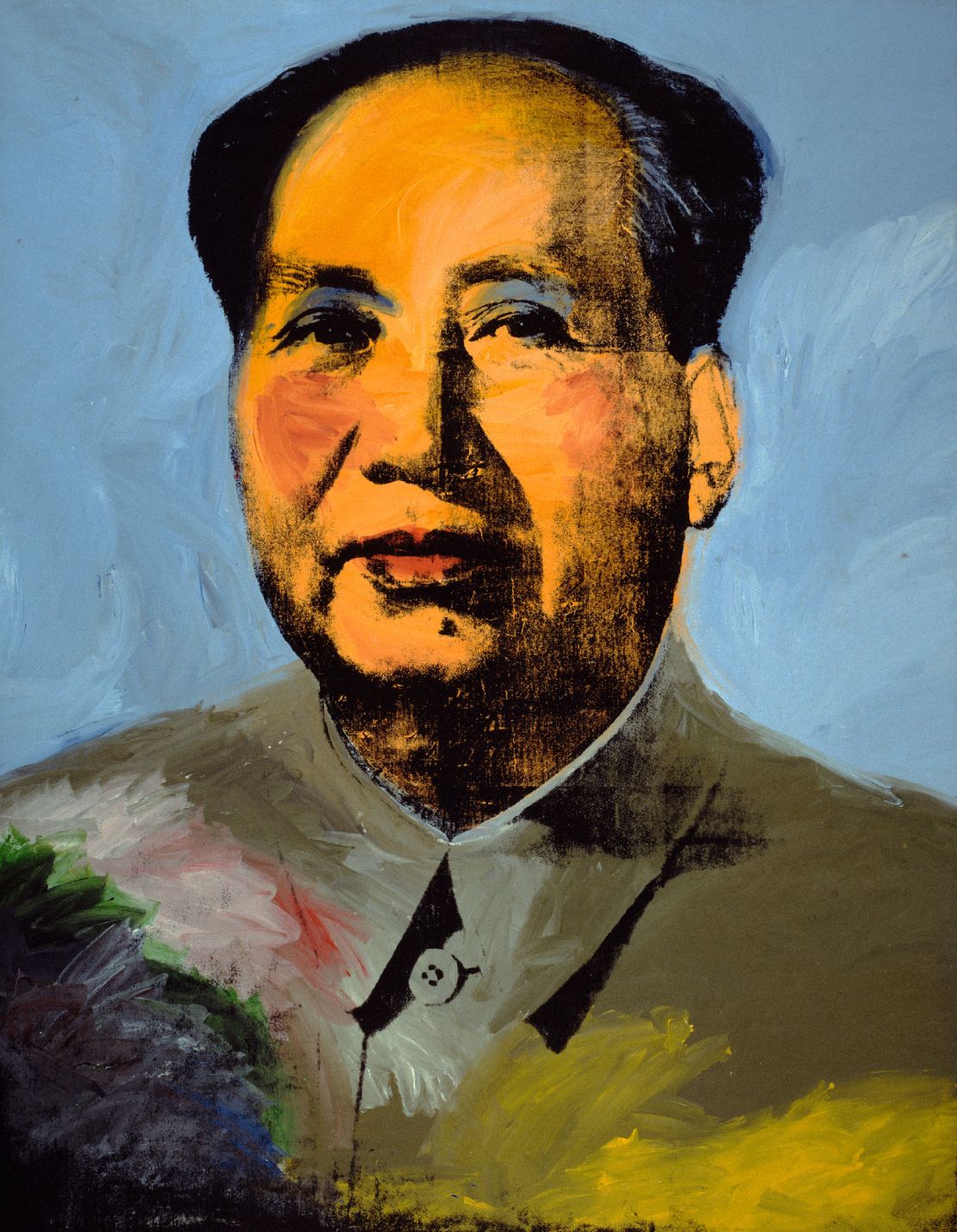

A big part of the exhibition is about challenging the critical perception that Warhol’s work fell off in the 1970s and ’80s, that it was somehow less interesting or more commercial. In fact, I think you see that Warhol continued to experiment, and that his investigations in painting actually became even more robust than they were in the 1960s.

Also – and this is a basic thing – people still think that Warhol didn’t know how to make art, or that he somehow didn’t know how to draw. But I think when you see the earlier work we have in the exhibition, from the 1950s, you’ll see that he’s a consummate draftsman.

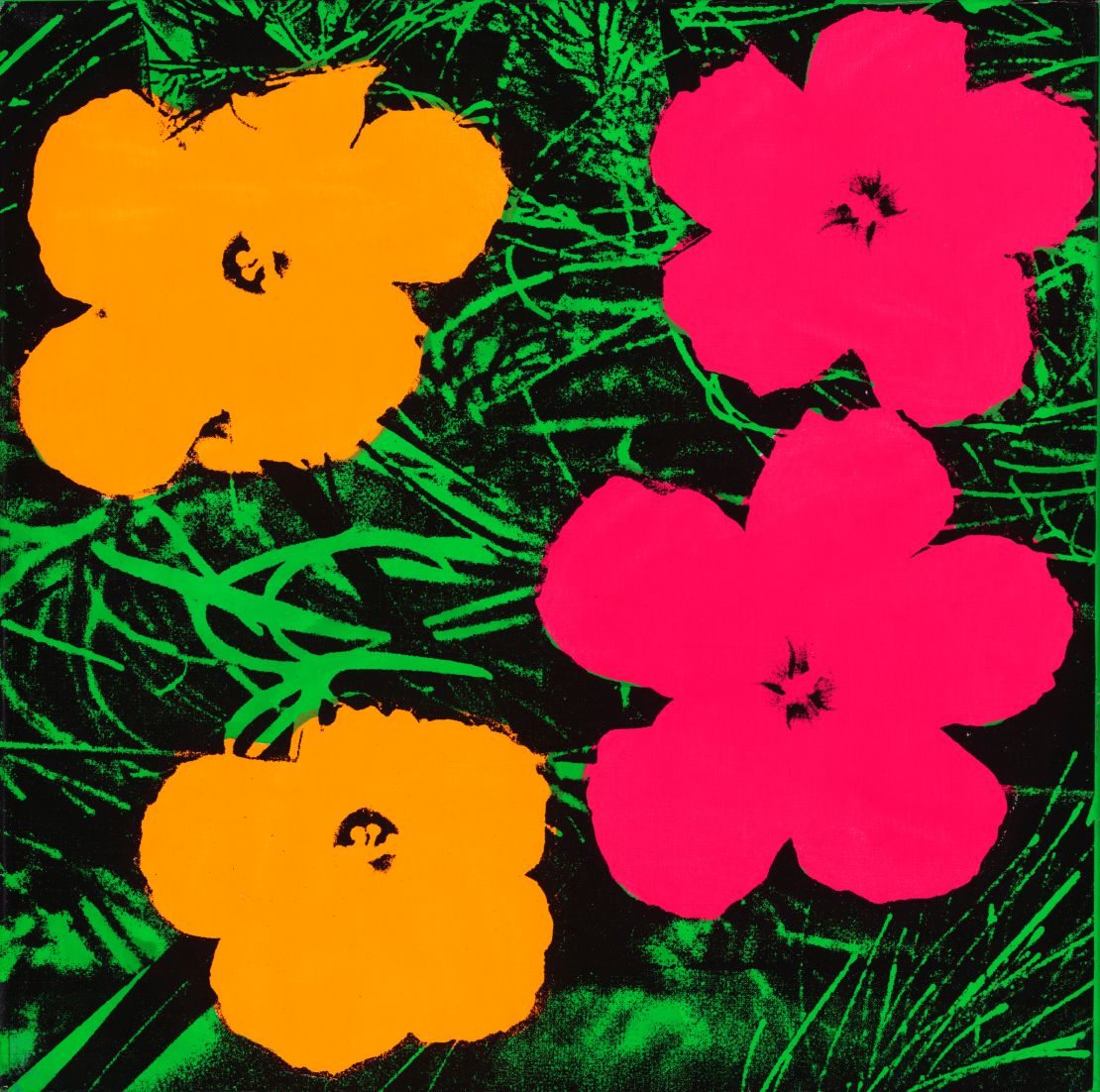

Ultimately, there’s just tremendous visual pleasure in seeing Warhol’s work. He was a brilliant colorist. Whether it’s his flowers, his sunsets or the optically charged image of an electric chair, he just had these extraordinary color combinations. That ability to draw us in visually is something very seductive that people still want to see.

Peggy Phelan, Warhol scholar

Stanford University professor Peggy Phelan and her colleague, Richard Meyer, have compiled a catalog selected from more than 130,000 mostly unseen photographs taken by Warhol. She and Meyer have co-written the book “Contact Warhol: Photography Without End,” and co-curated an exhibition of the same name at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center.

Warhol, perhaps more than any other 20th-century artist, stood at the threshold of countless different political, economic, social and cultural changes. He’s the linchpin in many ways. He influenced fashion and film, he wrote music and books, and he undertook so many enterprises. He’s just a colossal figure.

But Warhol remains an enigma – one that we’re far from exhausting.

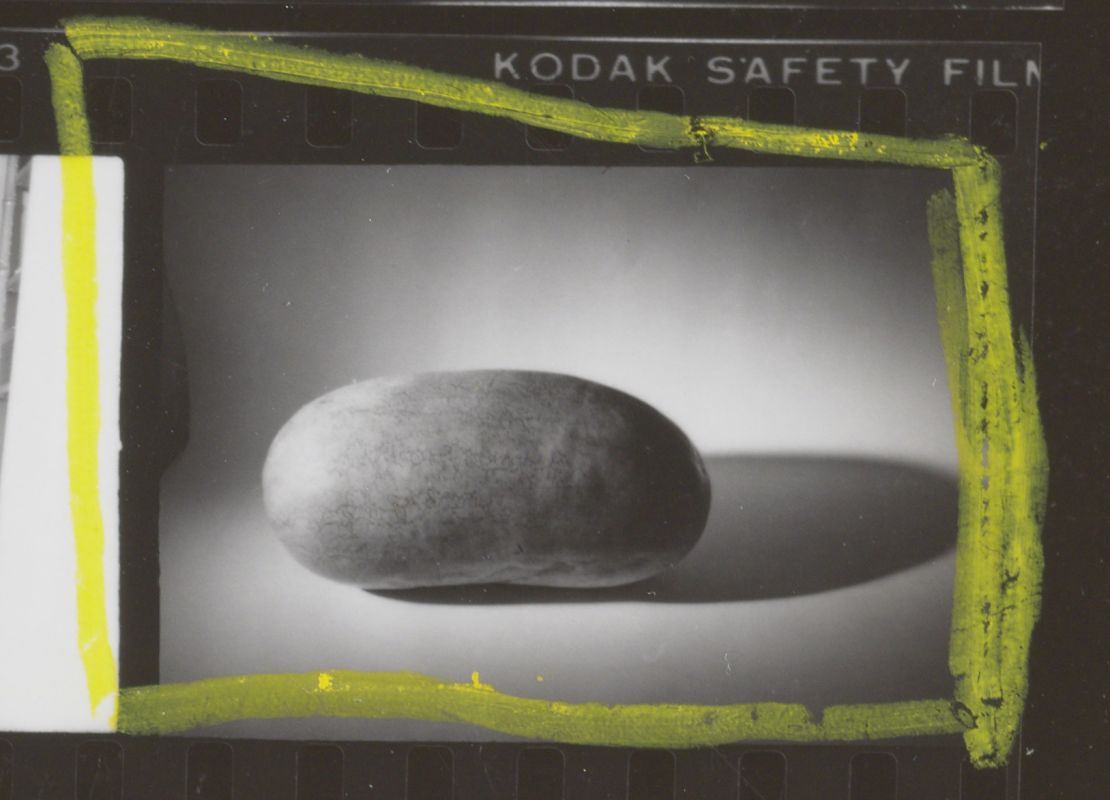

He took photographs daily for 11 years, and we’ve just added 130,000 of the images – only 17% of which had ever been seen before – to the body of work known as Andy Warhol. The archive reveals his fascination with the everyday. But he also used his camera as a distancing tool. His participation in the New York scene was as often as an observer rather than the center of attention. He’d rather take pictures than be in them.

The images show Warhol’s relationship with photography in such a vivid way. His photos can also be seen as rehearsals for bigger works. Before making his famous “Hammer and Sickle” silkscreens, for instance, he took hundreds of photographs of a hammer and sickle, placing them next to items like dollar bills or Big Macs.

You can see him thinking through different capitalist symbols and developing the concept. You can also see him going through the history of art, mastering its vocabulary, querying it and then turning it into a Warholian creation. There’s a common misconception that Warhol stumbled onto his great ideas, or that he borrowed them from different people. But, in my view, this archive makes that claim impossible. He was just so systematic and disciplined.

We’ve made the negatives and contact sheets available through an open-source digital archive. Anyone can look at them, and we hope others can answer questions about who Warhol was, and the context in which he lived.

New theories have already emerged as a result. For instance, new photographs of Warhol in drag have given us a new perspective on his understanding of the often coercive force of gender and queer performance. We now also know more about Warhol’s relationship with Jon Gould, a Paramount Studios executive with whom he was romantically involved. The unseen images reveal the depth of feeling he felt toward Gould, whose death from AIDS had a profound effect on Warhol.

To investigate the archive fully, I think we’re looking at 35 or 40 years of very rigorous scholarship. These things take a very long time to digest and absorb, so I’m not worried that we’re getting to the bottom of the barrel with Warhol.

Gul Coskun, Warhol dealer

Gul Coskun is the founder of Coskun Fine Art, a London-based contemporary art dealership focusing specializing in works by Andy Warhol.

I have been dealing in Andy Warhol since 1996, and from the start, I have been overwhelmed by the interest in his work. Most of my exhibitions were completely sold out before I’d even finished installing them.

My earliest buyers were young professionals, mostly in their early 30s. In those days, prices were very fair: You could buy a Jackie O canvas for $80,000 or a Queen Elizabeth print for $4,500.

Over the years, the Warhol market has gone from strength to strength, to such an extent that now even his prints and multiples are barely affordable to young collectors. Last year, “Sixty Last Suppers”?sold?at Christie’s for more than $60 million, and “Six Self Portraits”?went?for £22.6 million ($29.3 million) in London this March.?

Market-wise, 2014 was an exceptional year, with?“Triple Elvis” and “Four Marlons” going under the hammer for $81.9 million and $69.6 million respectively.?Warhols, collectively, made almost $570 million at auction that year, an annual?figure?that hasn’t been matched?since.?

But the recent dip in auction revenues?(last year’s figure was reportedly?59% down?on the 2014 peak) shouldn’t be read as a sign that?interest in Warhol is waning.?These totals can vary drastically based on a small number of high-value items, so they’re not necessarily indicative of the wider market. (Plus, private sales make up a significant portion of Warhol sales.) In fact, having bought and sold his work over the past two decades, I can say that interest has exploded in recent years. The public’s love of Warhol will only grow.

Prints and multiples, the most commonly traded form of Warhol’s art, are currently at an all-time high. Recent sales have also seen an increase in buyers from east Asia, which bodes well for the future.

This year’s auctions have demonstrated the dramatic price increases that can occur over a relatively short period of time. “Campbell Soup I,” which sold for less than $72,000 in 2002, went for around $1.2 million in March, and a portfolio of Marilyn Monroe silkscreens grew in value from from about $271,000 to more than $3.2 million over the same period. One of Warhol’s “Queen Elizabeth?II” images,?which sold for $4,370 in 1997, fetched?more than 50 times that at a recent sale.?

Warhol is, by far, the most popular American pop artist of the 20th century. No private or museum collection is complete without his work, and the themes he addresses remain hugely relevant. The ever-increasing popularity of Warhol demonstrates how much his work still means to people.

As told to CNN’s Oscar Holland. Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.