Modern humans aren’t the only ones who love to wear jewelry.

More than 120,000 years ago, prehistoric humans were using shells as beads on a string to make what we now call a necklace, according to a new study.

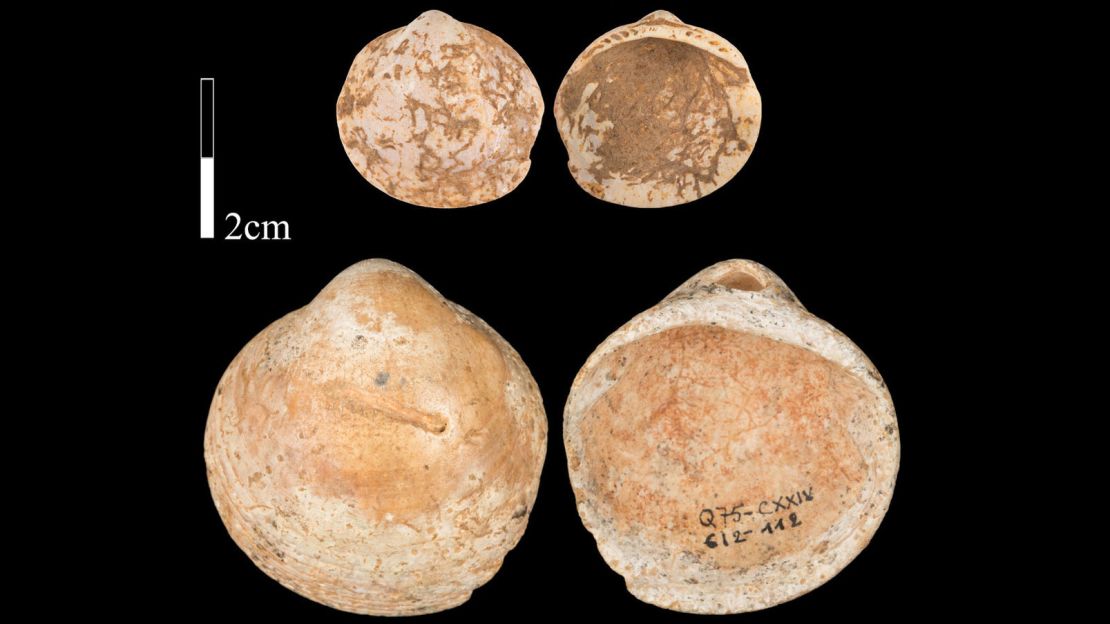

Such shells were found directly under human graves at the Qafzeh Cave, which is in Israel near the Mediterranean Sea. For the study, which published in the journal PLOS ONE on Wednesday, the researchers gathered the same species of shells found in the cave and conducted experiments on them.

These are one of the oldest adornments humans created, said Daniella Bar-Yosef Mayer, collections manager for paleontology and archaeomalacology (the study of mollusk remains at archeological sites) at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University.

To find out how the shells had been used, the researchers first simulated the possible wear and tear on the specimens using various materials, such as sand and leather. After the abrasion, they hung the shells on wild flax string to simulate the wear shells would’ve had were they strung together.

They found that the abrasions observed in the experiment matched those on the original shell specimens. Not only did the shells show patterns similar to being hung on a string, but they also showed abrasions with other shells, which means they were strung close together.

Bar-Yosef Mayer, who is also an associate at the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, said she also found ochre smeared on four of the five shells they examined.

“Ochre was a substance to color various materials in red and was often used by prehistoric humans, possibly for painting their bodies, for processing hides, and more,” Bar-Yosef Mayer said. “Possibly, giving the shells a red color also had symbolic meanings.”

The shells themselves could have also had a greater meaning to the people who wore them, according to Bar-Yosef Mayer.

“They could indicate the group identity of the person carrying it, their status in society, or they could reflect certain beliefs,” Bar-Yosef Mayer said.

The humans who collected the shells were Homo sapiens who developed in Africa between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago and migrated north to Europe and east to Asia, Bar-Yosef Mayer said.

“They were hunter-gatherers who lived off the land, but at that point started engaging in additional activities that had a more symbolic nature, and of which we do not [know] much, but we have the shells as the earliest physical evidence of non-utilitarian artifacts,” Bar-Yosef Mayer said.

The researchers also collected shells found at Misliya Cave, which is farther west and closer to the Mediterranean Sea. Those shells dated back 160,000 years ago and were non-perforated, which showed no indication of humans manipulating them, according to the study.

The gap between the collection of non-perforated shells and perforated shells can shed some light onto the creation of string, according to Bar-Yosef Mayer.

“For the first time, we attempted to identify when string was invented and used,” Bar-Yosef Mayer said.

Bar-Yosef Mayer said that beginning to identify the invention date of string using shell samples from the two caves is one of the main takeaways from this study because it reveals more about human evolution.

“What is important is that the older ones were collected by humans and transported to their cave site, and but the younger ones also had use wear that showed they were suspended,” Bar-Yosef Mayer said.