Editor’s Note: This story was produced as part of CNN Style’s The September Issues, a hub for facts, features and opinions about fashion, the climate crisis, and you.

Sri Lankan fashion designer Amesh Wijesekera has become known for his colorful designs that combine local handwoven textiles with deadstock fabric to create distinctive pieces.

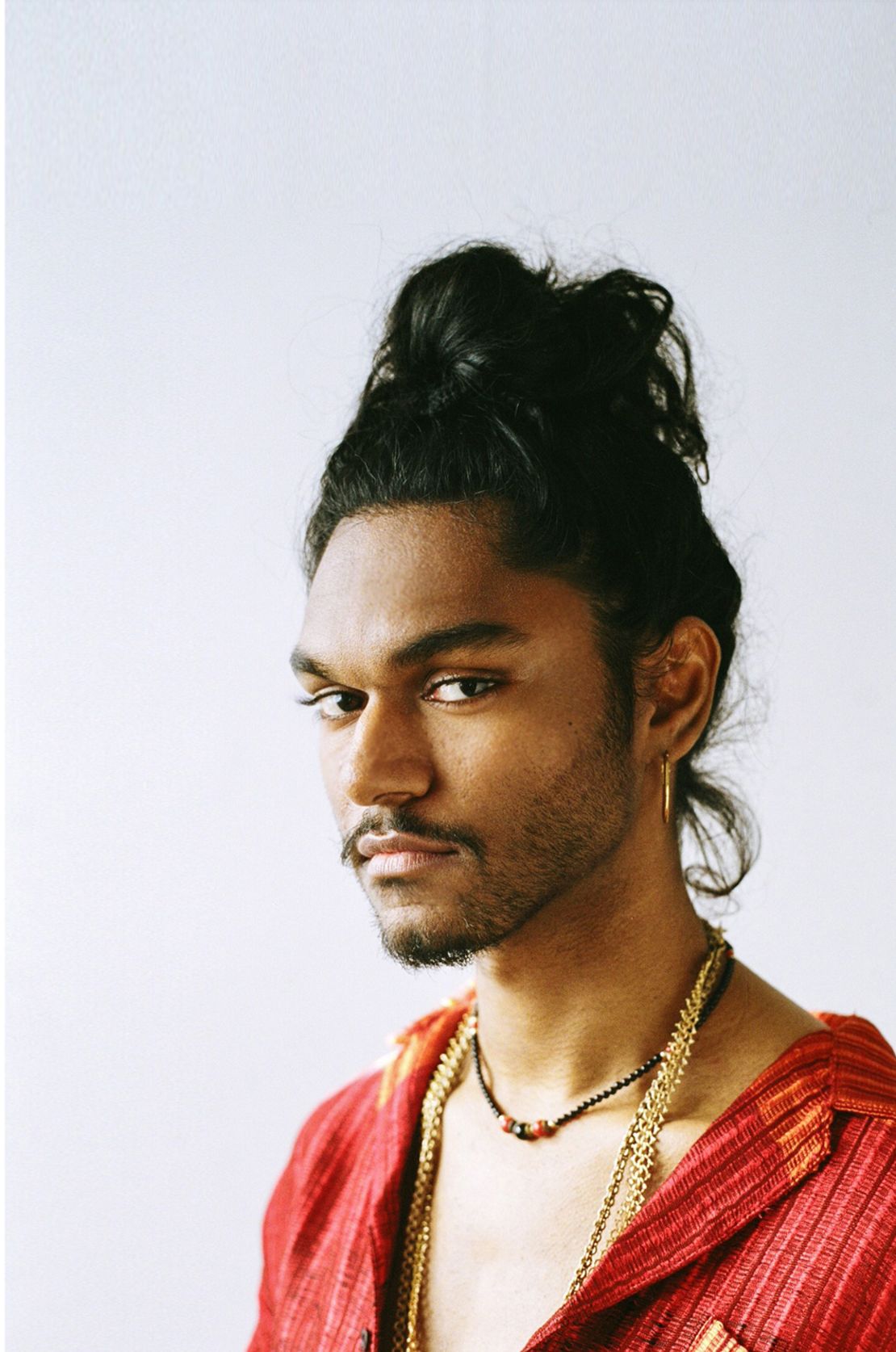

“My work is all about celebrating a new version of Sri Lanka and representation of South Asian beauty,” Wijesekera said over the phone. “When I moved to London I questioned: How can I share who I am to the world? How can I share my story, where I come from? and it came out through my fashion.”

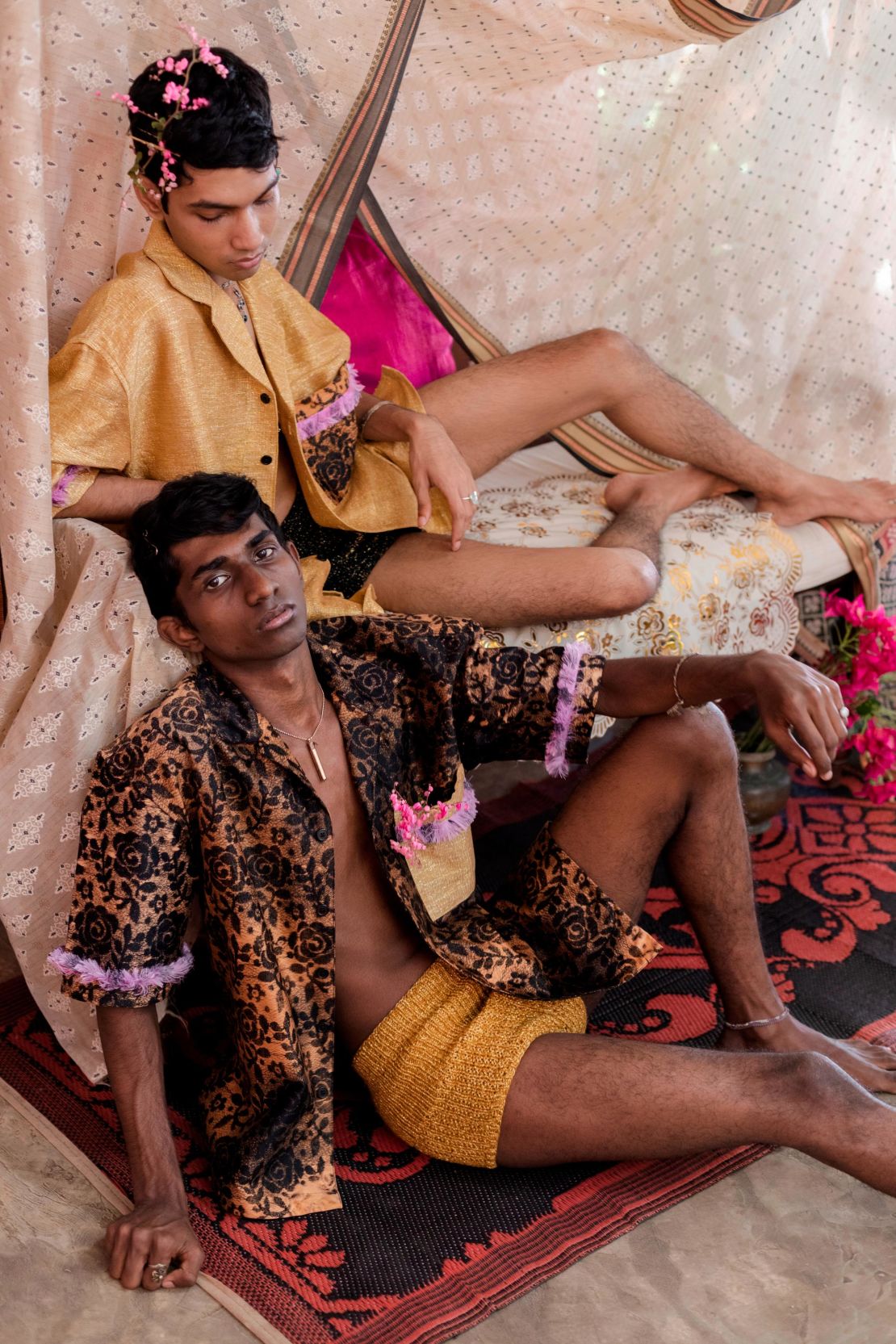

Wijesekera’s vision is a modern take on artisan handloom fabric, a Sri Lankan heritage craft not often seen on international runways. Sewn into loose-form coats, jackets or trousers, Wijesekera’s designs fuse his heritage with Western silhouettes and are made to be worn by anyone – irrespective of gender – as seen at his runway shows.

“I never really understood labels in general. I just want to create beautiful shapes and colors,” he said of his gender-inclusive approach. “Whoever wants to wear (my designs) can wear them.”

On Wijesekera’s Instagram page, he consistently showcases models of darker complexions, who are friends or people he has scouted on his own. “(They are) never from agencies,” he said. “I am a dark brown person with frizzy curly hair and that is all part of my identity; my idea of beauty.”

The designer began his career in 2015 after graduating from the Academy of Design in Colombo, Sri Lanka. He debuted his thesis collection at the capital city’s prestigious Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week on the sustainable fashion runway, followed by Graduate Fashion Week in London, and won awards at both shows. Since then, he has presented at Berlin Fashion Week and London Fashion Week and has been featured in Vogue Italia.

Though Wijesekera has built much of his career internationally, the designs under his eponymous label turn to his home country for inspiration. “While the island is well-known for its beautiful beaches and tourism, we also have a massive crafting industry,” he said. “I have always centered my work around making use of everything in Sri Lanka.”

By collaborating with local artisans in almost every element of his designs – hand-looming, knitting, crocheting, printing – he is able to support a centuries-old craft and think sustainably. “When creating a collection, I go to their homes in the weaving villages and we work together,” he said. “They have all the knowledge on the craft and craftmanship and I bring the new ideas with the designs.”

And by working with artisan weavers, Wijesekera is able to provide the predominately female workforce with employment and fair wages. “I basically try to get the artisan to be involved as much as possible. I want it to be a collaboration,” he said.

Wijesekera also uses waste, specifically from countries that have discarded excess materials in the Global South. “A lot of Western countries send their wool to Sri Lanka for manufacturing, and all excess yarns are burnt,” he said, “I incorporate the leftover yarns into my designs…based on what I find. That’s what makes it more interesting because each item almost becomes a one-off piece.”

His creative response to waste is consistent with other emerging designers. London-based Priya Ahluwalia creates her designs from deadstock and looks towards her Indian-Nigerian heritage for inspiration. Similarly, UK-based designer Bethany Williams is committed to sustainable practices and uses waste to create her garments, which often comment on social issues.

With the environment in mind, Wijesekera ensures that his designs are entirely handmade. “There are no machines used anywhere,” he said. He also refrains from purchasing new material. “I never buy fabric off the shelf and I don’t tend to make them.” Instead, he enjoys the creative challenge of making something new from what he can find in local markets, where deadstock fabric or unusable stock from local garment factories can be found.

“From Calvin Klein to Tommy Hilfiger, all the excess fabric is sold to the markets… it’s like a treasure hunt,” he said.

Wijesekera’s mosaic garments are characterized by a clash of textures and sunset-hued fabrics, which are often scavenged from Colombo’s Pettah Market. “I usually find beautiful fabrics, but they’re often damaged with holes,” he said. “After treatment the fabric has its own identity. I leave my ‘Amesh’ stamp on it” – giving fabric that may have ended up in a landfill a second life.”

Wijesekera also leaves his stamp by creating clothing that breaks down gendered labels, influenced by the way he was raised. “My mother sent me to ballet. I used to play with my sister’s dolls,” he said of his childhood. “I’d always wear my mother’s clothes or my grandma’s old trousers.”

His recent Spring-Summer 2020 collection, “Flower Boys,” continues his deconstructions of gendered stereotypes, with his male models dressed in fuchsia embroidered shirts and low-cut knitted vests. “The shapes aren’t overly feminine or overly masculine,” he said. “It’s at the borderline, where it could be anything. It’s all about how you style it, your personal style of expression and your identity.”

Subverting ingrained mentalities and societal norms is central to Wijesekera’s brand, particularly as he does not fit within certain boxes himself. “Being a queer person, I know the everyday struggles in this country unfortunately (even though I love it so much).”

Wijesekera’s followers seem to appreciate his efforts. “A lot of Sri Lankans message me saying that my work is inspiring them to be themselves,” he said. “That makes me really happy; it’s the biggest achievement. My work means something to people and helps foster their identities.”