The truthtellers

By Julia Hollingsworth and Yong Xiong.

Designed by Sarah-Grace Mankarious, Jason Kwok and Marco Chacón.

Untitled

They all had information Beijing wanted wiped from the collective memory.

Chen Kun

"We know you covered up the outbreak in 2003, and we believe you will cover up the epidemic this year again."

Untitled

No more 404.

One Monday morning, Chen Meiⓘ didn’t log on for work.

It was spring in the Chinese capital Beijing, and the non-profit organization that the 27-year-old worked for was operating remotely as coronavirus continued its spread.

Concerned, Chen Mei’s boss called his brother, Chen Kunⓘ, who hadn’t heard from his sibling. Immediately, Chen Kun had a bad feeling. His brother had been republishing sensitive articles about the early days of the pandemic, some of which were later removed by Chinese censors. When Chen Mei’s workmate reported his disappearance to the police, officers said he had been taken away for investigation.

That was 10 months ago. Chen Kun hasn’t seen his brother since.

Chen Mei is among a number of truthtellersⓘ the Chinese government has allegedly tried to silence for sharing information that diverges from the official narrative, information that activists allege Beijing wants wiped from the collective consciousness.

Some were doctorsⓘ who tried to warn of a deadly new virus in Wuhan, or citizen journalists who documented hospitals stretched to breaking point with bodies piled outside. Others, like Chen Mei, tried to preserve evidence of the unfolding crisis online, even in the face of widespread censorship.

The truthtellers laid bare how slow authorities were to warn the public, and the world, about the enormity of the coronavirus threat. Their stories contrasted with the narrative pushed publicly by the Chinese governmentⓘ that it was on top of the dangerous virus and was preventing its devastating spread. The evidence they sought to share is crucial to understanding the timeline of the virus, so the world can prevent another pandemic of this scale happening again.

A year on, the truthtellers’ legacy is unclear. Many have paid a heavy priceⓘ for their work. Some have been detained. Others are missing. One even died as he tried to bring the full story to light.

Chen Mei

Chen Mei in 2019

Chen Kun

Chen Kun holds a picture of his brother in front of the United Nations building in Geneva.

truthtellers

Truthtellers, noun

In this case meaning:

Citizen journalists, doctors and archivists who revealed what was happening in the early days of the pandemic.

doctors

Dr. Li Wenliang alerted fellow doctors about the new SARS-like virus spreading in December 2019.

Chinese government

Wuhan CDC director Li Gang said on Jan 19, 2020 that “the transmissibility of this new coronavirus is not strong.”

Zhang Zhan

- Zhang Zhan

- What she found

- Documented harsh realities of Wuhan life between early February to mid-May, including overflowing hospitals and empty shops.

- What happened

- Sentenced to four years in prison for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

Censorship in China

China’s internet ecosystem is heavily controlled by the government -- but users are always trying to find new ways to evade detection from the censors. Here’s how it works.

Many Western internet sites aren’t available in China without a virtual private network (VPN) that helps users cross the country’s vast censorship apparatus, known as the Great Firewall.

There’s one error code all internet users are familiar with: 404.

It means a page cannot be found -- in China, that’s often because it has been censored.

To keep content that has been 404’d alive, Chinese internet users deploy a range of creative methods without the inflammatory key words censors search for.

Chen Mei’s solution to China’s censorship was Terminus 2049, a crowd-sourced repository for sensitive articles that he and his friend Cai Wei co-founded in 2018 on GitHub, a US-owned platform favored by software developers as it allows them to share code and collaborate on projects remotely.

To Chen Kun, the purpose of Terminus 2049 was very simple.

“They wanted people to see the complete picture of these important social events so that they could understand the real China,” he said. “You are censoring, I am archiving, you want it to disappear, I want to save it, and spread it. That’s the ultimate goal.”

It was only when Termnius 2049 started memorializing articles about Wuhan that the authorities took action.

All of these sites are blocked in China.

Google, for example, is not visible in China.

This is what a 404 error looks like.

Here’s what a user sees when they try to access a censored article on Chinese social media platform WeChat -- in this case, an interview with Dr. Jiang Yanyong, a whistleblower during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak

This picture of Dr. Ai Fen, who was one of the first to raise the alarm about Covid-19, is censored on Chinese social media platform Weibo. The message says: “No permission to view.”

This is what a censored news report looks like -- in this case, on Chinese news outlet Phoenix New Media.

This error message appears when anyone in China tries to load YouTube.

This is an interview with Dr. Ai Fen where some characters have been substituted for emojis.

And here is that same interview -- this time, in a video that mimics the opening credits of the Star Wars movies.

This is Terminus 2049 on GitHub. When a user spotted an article on a controversial topic, they could send it to Terminus 2049 and the site’s bot would automatically save the article’s content and republish the text on Terminus 2049. GitHub is US-owned, meaning the saved stories were out of the Chinese government’s reach.

While certain pages hosted on GitHub are sometimes blocked by China’s Great Firewall, the platform itself is still accessible, because software developers there rely on it to share code.

That meant that regular internet users in China could access Terminus 2049, and its archived articles, even without a VPN.

Chen Mei and his fellow Terminus 2049 users initially posted articles about migrant evictions, then stories of sexual assault emerging from the #MeToo movement -- anything they wanted to save from the censors.

Terminus 2049 is a reference to a planet on the edge of the galaxy in a series by American science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov.

Chen Kun believes his brother’s goal in setting up Terminus 2049 wasn’t to advocate for a single issue, but to fight for a free internet. Terminus 2049’s About page sums it up: “No more 404.”

Meet the truthtellers

Chen Mei was perhaps an unlikely hero of the coronavirus pandemic.

Chen Mei

- Chen Mei

- What he did

- Archived and republished articles about the early days of the coronavirus on Terminus 2049, including interviews with Ai Fen and Li Wenliang, and a Caixin investigation into the early days of the outbreak.

- What happened

- Detained on April 19, 2020, and charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” He is still awaiting trial.

A shy but passionate zoology graduate, he worked for a non-profit that helps people with hearing loss, according to his brother Chen Kun. He loved cats and kept a low profile online, said a friend who asked not to be named out of fear of punishment from the authorities.

“He was never the initiator of projects -- he always played the supporting role,” said Chen Kun.

But with Terminus 2049 he made an exception.

“You might have to be more cautious about this,” Chen Kun remembers telling his brother, reminding Chen Mei that if he could see his posts about Terminus 2049, then others could, too.

Even so, Chen Kun didn’t think his brother would be arrested as what he was doing was relatively conservative compared to other activists. But under China’s system of information control, the rules are always shifting.

Chen Qiushi

Source: Chen Qiushi/YouTube

- Chen Qiushi

- What he found

- Reported in late January that Wuhan hospitals and doctors were overworked and lacking in supplies.

- What happened

- Mother previously said he had been forcibly quarantined. Believed to be in Qingdao, China. Chen Qiushi’s friend Xu Xiaodong, a famous mixed martial arts fighter in China, said in a YouTube video that Chen had not been charged and was safe and healthy, but was living under state supervision.

Fang Bin

Source: Fang Bin/YouTube

- Fang Bin

- What he found

- Documented body bags piling up outside a Wuhan hospital.

- What happened

- Went missing after posting a video on February 9, 2020. Has not been heard from since, location unknown. Believed to be detained.

Li Zehua

Source: Li Zehua/YouTube

- Li Zehua

- What he found

- Disguised himself as an applicant hoping to work at a Wuhan crematorium and spoke with the recruiter about what would be expected of him so that he could gather evidence of how many people had died. Revealed how state security was trying to silence citizen journalists like him.

- What happened

- Posted video on February 26, 2020 where he said he was being chased by state security before going missing. In April, he published a video saying that he had been put into forced quarantine, and released hidden camera footage that he said showed police coming into his room and taking him away.

Zhang Zhan

Source: Zhang Zhan

- Zhang Zhan

- What she found

- Documented harsh realities of Wuhan life between early February 2020 to mid-May, including overflowing hospitals and empty shops.

- What happened

- Sentenced to four years in prison for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

Cai Wei

Provided to CNN by Chen Kun

- Cai Wei

- What he did

- Archived and republished articles about the early days of the coronavirus on Terminus 2049, including interviews with Ai Fen and Li Wenliang, and an investigation by Chinese media outlet Caixin into the early days of the outbreak.

- What happened

- Charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” He is still awaiting trial.

Ai Fen

Source: Wuhan Central Hospital

- Ai Fen

- What she did

- One of the first doctors to attempt to raise the alarm on the spread of a new coronavirus in December 2019; her interview with Chinese media prompted an online movement to fight against government censorship. Ai would later become known as the “whistle-giver.” As she told media, she wasn’t the whistleblower, just the one who provided the whistle.

- What happened

- Interviewed by the Disciplinary Committee of her hospital and accused of spreading rumors. No known punishment, appears to still be working as a doctor in Wuhan.

Li Wenliang

Source: Li Wenliang

- Li Wenliang

- What he did

- Alerted fellow doctors about the new SARS-like virus spreading in December 2019, gave media interviews on the early days of the pandemic in January.

- What happened

- Called to a Wuhan police station on January 3, 2020, where he was reprimanded for spreading rumors on the internet, and told to sign a statement acknowledging his misdemeanor. Tested positive for coronavirus on February 1, 2020, and died on February 7, 2020, from coronavirus.

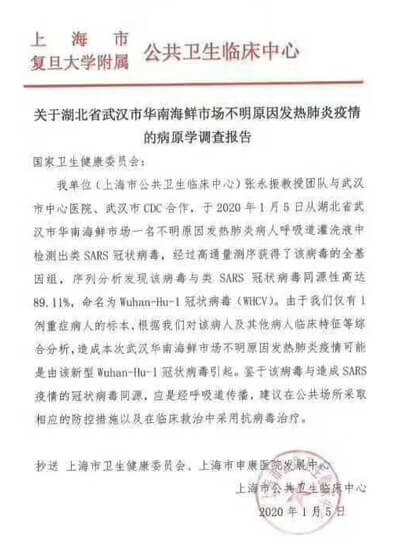

Zhang Yongzhen

- Zhang Yongzhen

- What he did

- His team sequenced the genome, and were the first to release it publicly. The Chinese government released the genome the following day.

- What happened

- His lab was temporarily closed 'for rectification' the day after he published the genome sequence information. He is still working to trace the origin of the coronavirus.

It’s not always immediately clear where the red line is for censorship, and because the rules aren’t static, some people venture into gray areas in the belief that what they are doing will be tolerated by the government. They hope that they will be lucky enough to avoid censorship and potential punishment.

“It’s really unclear what is legal and what is illegal,” a friend of Chen Mei noted. “Why would archiving those articles be illegal?”

When Chen Kun got that fateful call on April 20 from his brother’s boss, he was in Indonesia, trying to avoid the pandemic. His brother Chen Mei had disappeared alongside Terminus 2049 co-founder, Cai Wei, and Cai Wei’s girlfriend, he soon learned.

Chen Kun and Chen Mei.

At the beginning of May, Chen Mei’s parents received a notice via courier from police which confirmed their suspicions: their son was under residential surveillance at a designated location, a system whereby people can be held for up to six months without charge.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and State Council Information Office have not responded to requests for comment on case statuses of Cai Wei and Chen Mei, and fellow truthtellers Chen Qiushi and Fang Bin. They did not confirm how many people had been detained or prosecuted for sharing information on the pandemic. China’s Cyber Security Administration has not responded to a request for comment on whether archiving and republishing Chinese news reports is illegal.

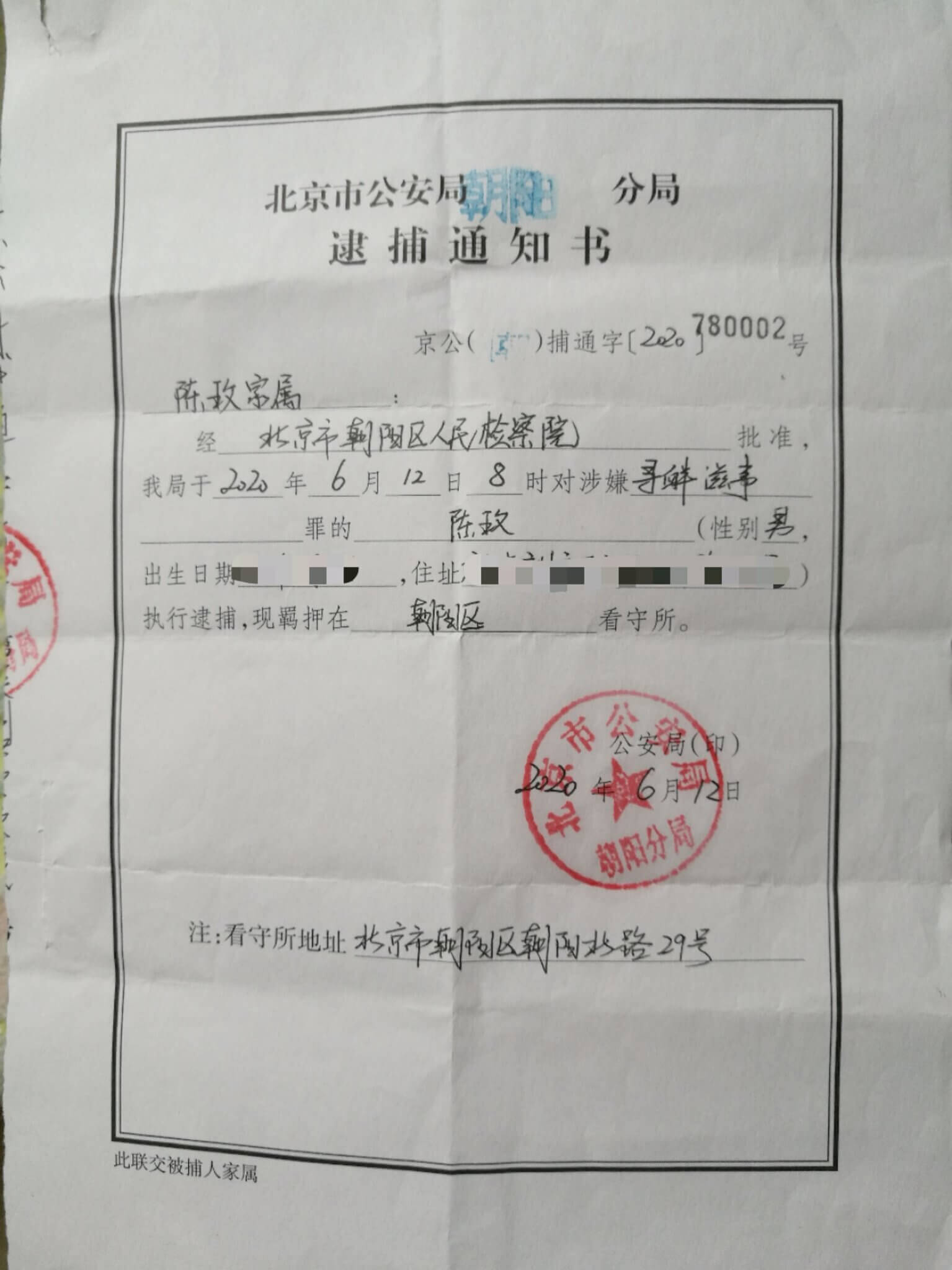

This is the arrest warrant for Chen Mei issued by Beijing Public Security Bureau on June 12, 2020.

Provided to CNN by Chen Kun

Chen Kun had already spent time in detention in Beijing back in 2014. He said he was arrested after his girlfriend put up posters in the city supporting Hong Kong’s pro-democracy Umbrella Movement. Authorities believed he ordered her to do it.

“It wasn’t my plan to study in Paris,” he said. “I would have gone back to China after the pandemic if it weren’t for my brother.”

He worries for his family left in China, including his mother, who the Chinese authorities have contacted to ask about Chen Mei’s political activities, although she knew nothing.

“I’m worried, but I don’t have any choice. I just have one option which is to speak out,” Chen Kun says.

Chen Kun says if people can only see the “whitewashed” version of history promoted by the Chinese government, there will be no way to learn from this current outbreak.

“Then what was the sacrifice of this year for?” he says.

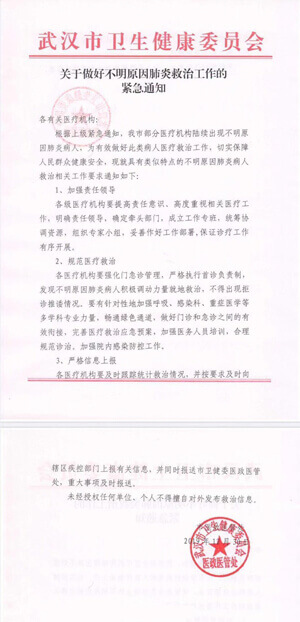

Timeline of the initial outbreak

In the year since Covid-19 emerged in China, Beijing has pushed its version of events to a domestic and global audience. But the truth can be found in articles that were archived before censors swept through Chinese-language media.

CNN has constructed an unofficial timeline of the first few months of the pandemic based on reports by citizen journalists and articles posted on GitHub sites -- including Terminus 2049.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and State Council Information Office have not responded to requests for comment on accusations that officials delayed warning the Chinese public about Covid-19. Both bodies and the Cyber Security Administration did not reply to requests to explain why news reports from the beginning of the pandemic were censored.

No official reports of a novel coronavirus.

A 65-year-old deliveryman linked to the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan is admitted to Wuhan Central Hospital after developing a fever three days earlier.

Source: Caixin, February 26, 2020

No official reports about a novel coronavirus.

A private company is asked to run a genomic test on a swab sample from the deliveryman and finds a new coronavirus.

Source: Caixin, February 26, 2020

Still no official reports about a novel coronavirus.

Zhang Jixian, a respiratory doctor at Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine in Wuhan, alerts her hospital to four unusual pneumonia cases. Her actions aren’t made public until February, when Chinese state media praises her as the first doctor to report the virus.

A 41-year-old man with a fever is transferred to the Wuhan Central Hospital for treatment. He has never been to Huanan Seafood Market.

Source: Caixin, February 26, 2020

Ai Fen, the head of Wuhan Central Hospital’s emergency department, receives a patient’s test result that reads: “SARS coronavirus.”

Terrified, Fen circles the test report in red and sends a photo of it to doctors in her department. That night, the test result circulates among the city’s doctors on Chinese social media app WeChat.

One of the doctors who shares the news is Li Wenliang, a 33-year-old from the same hospital. He tells friends on WeChat that seven patients from a local seafood market have been diagnosed with a SARS-like illness.

That day, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission tells the city’s medical institutions that a series of patients from a local seafood market have an “unknown pneumonia” but warns them not to release unauthorized information to the public.

Sources: Chinese magazine People, March 10, 2020, Beijing Youth Daily, January 27, 2020

Source:Wuhan Municipal Health Commission

Chinese authorities notify the World Health Organization (WHO) about a cluster of pneumonia cases, but do not specify how many are sick, or what kind of virus it might be.

Dr. Li is reprimanded by his hospital and the local health commission for spreading reports of the virus.

Source: Caixin article, January 31, 2020.

Wuhan authorities shut the Huanan Seafood Market.

In a Weibo post, the Wuhan police say it has dealt with “eight rumormongers” according to the law.

Images taken by a Wuhan resident in December 2019 show animals being sold in the Huanan Seafood Market before it was closed.

Source: Winterson Weibo

Footage from inside the Huanan Seafood Market filmed by a Wuhan resident.

Source: Winterson Weibo

Dr. Fen is reprimanded by Wuhan Central Hospital for sharing information.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences Wuhan Institute of Virology sequences the virus.

Source: Chinese magazine People, March 10, 2020; Caixin, February 26, 2020

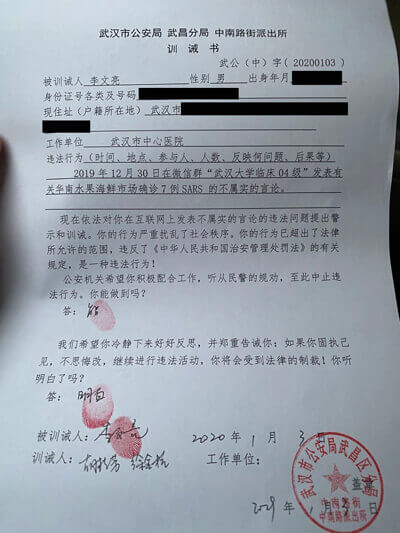

Dr. Li is told to go to the police station where he’s ordered to sign a letter admitting to rumormongering.

Source: Beijing Youth Daily, January 27, 2020

The letter Li Wenliang signed at the police station.

Source: Li Wenliang

Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center professor Zhang Yongzhen and his team sequence the virus’ genome, and in a document to the National Health Commission they suggest taking preventative measures at public places.

Source: Caixin, February 26, 2020

The letter from Zhang’s team.

Source: Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center

Chinese President Xi Jinping holds a Politburo Standing Committee meeting on how to contain the coronavirus. The meeting in’t made public until it is reported by state media on February 15.

Wuhan holds its annual parliamentary meetings between January 6, 2020 and January 10, 2020. There is no mention of the new virus in official discussion sessions.

Source: Wuhan Radio and TV Station

Scientists say a new coronavirus is responsible for the outbreak -- the same family of viruses behind SARS and the common cold.

China reports the first official coronavirus death.

The sequenced genome is posted on open-source site virological.org on behalf of professor Zhang. That allowed scientists to tell which virus test kits were effective.

In the first weeks of January, Dr. Ai keeps quiet, although she warns her husband to avoid busy public places. She tells hospital staff to wear protective gear. When management refuses to let them wear hazmat suits as it would frighten patients, Ai tells them to wear full body protection under their clothes.

On January 11, Dr. Ai learns that a nurse in her emergency room is infected. At the end of a meeting with the hospital’s medical affairs administration, the hospital directs her to change the nurse’s medical report from “two lung infections, viral pneumonia,” to “scattered infections on both lungs.”

Source: Chinese magazine People, March 10, 2020

The Chinese government shares the genetic sequence of Covid-19. Authorities maintain there is no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission, and no healthcare workers have been infected.

Dr. Li is admitted to hospital -- he is later diagnosed with coronavirus. As more patients arrive at the hospital, Dr. Ai starts to believe the virus is transmitting between humans not from animals, as authorities have said.

Source: Chinese magazine People, March 10, 2020

The WHO says there is no clear evidence that the virus spreads human-to-human, citing Chinese officials.

January 17, 2020

The WHO reiterates its statement that there are no reports of medical workers contracting the virus.

January 19, 2020

China’s National Health Commission says that coronavirus remains “preventable and controllable.”

Wuhan CDC director Li Gang says on January 19, 2020 that the “transmissibility of this new coronavirus is not strong” and “the risk of continuous transmission is low.

Source: Changjiang Daily

Chinese government-appointed expert Dr. Zhong Nanshan announces on national TV that the virus can transmit from human to human. The virus has already infected more than 300 people, mostly in China, according to official numbers, and spread to more than three countries. China is not yet reporting asymptomatic cases.

President Xi Jinping, in his first public comments on the coronavirus, orders “resolute efforts” to control the outbreak.

Zhong Nanshan speaking on January 20, 2020.

Source: CCTV

Terminus 2049 posts its first coronavirus-related article, a 2003 Time magazine interview with Chinese physician Jiang Yanyong, who exposed how Chinese officials had downplayed the spread of SARS.

To Chen Kun, the purpose of reposting that previously censored article was obvious: “We know you covered up the outbreak in 2003, and we believe you will cover up the epidemic this year again.”

Dr. Ai’s emergency department is swamped. More than 1,500 people arrive that day, three times as many as normal. Of those, 655 have a fever.

Doubts creep in about the accuracy of China’s reported coronavirus case numbers. Scientists at Imperial College London estimate that by January 18, around 4,000 people were likely to have had symptom onset in Wuhan city alone.

Source: Chinese magazine People, March 10, 2020

A nurse shouts at people in a hospital corridor in Wuhan.

Source: Twitter

The government’s official tally of coronavirus cases reaches 548.

The WHO publicly acknowledges the presence of human-to-human transmission. It is publicly positive about China’s response.

China takes the unprecedented step of putting Wuhan and some neighboring cities into strict lockdown. At the time, China has reported just over 830 coronavirus cases and 25 deaths.

CNN was in Wuhan when the lockdown went into effect on January 23, leaving on one of the last trains out of the city.

Skepticism grows over the official narrative. Members of the public begin documenting what they see: overrun hospitals and infections spreading among medics.

Some, like lawyers Chen Qiushi and Zhang Zhan, travel to Wuhan to document what’s happening.

Source: Chen Qiushi YouTube

Source: Chen Qiushi YouTube

Chen arrives in Wuhan on January 24 while Zhang arrives at the start of February. Both post videos documenting the grim reality online, including to YouTube, a platform that can only be accessed in China by a virtual private network.

Source: Zhang Zhan YouTube

Another citizen journalist, Li Zehua, arrives in Wuhan in February and posts videos alleging that the busy crematoriums indicate the death toll is likely higher than the official number.

Wuhan businessman Fang Bin posts a video of corpses piling up outside a hospital.

Source: Fang Bin YouTube

Wuhan writer Fang Fang begins an online journal documenting daily life under lockdown. Two months’ worth of her diary recordings remain preserved on another GitHub site, Lest We Forget Wuhan 2019, and are later turned into a book.

Source: Terminus 2049, Lest We Forget Wuhan 2019

Dr. Li is admitted to the intensive care unit. From there, in the last days of his life, he conducts an interview with Beijing Youth Daily. It is later censored.

Source: Beijing Youth Daily interview, January 27, 2020

Li Wenliang in an ICU bed

Source: Li Wenliang

One of China’s propaganda chiefs announces that more than 300 journalists had been deployed to Wuhan to “publicize how the government makes preventing and controlling the outbreak a top priority.”

Source: CCTV

Chen Qiushi goes missing. Soon, both Fang Bin and Li Zehua disappear, too.

At night, the news that Dr. Li Wenliang may have died spreads across Chinese social media. State media report that he is dead but delete those tweets after the Wuhan Central Hospital releases a statement saying Li is being resuscitated.

Source: Li Zehua YouTube

Officials confirm Li’s death. There’s an outpouring of grief and fury online that poses an extraordinary challenge to Beijing. China begins its crackdown on truthtellers.

The government says 1,716 health workers have been diagnosed with coronavirus and six have died. At the time, China had reported more than 66,000 cases.

Chinese media outlet Caixin publishes a story, later censored, that reveals the account of Wuhan doctor Zhao Su, who spoke of the deliveryman being admitted to hospital with a fever.

Wuhan’s top party official announces the government will promote “gratitude education” to help citizens thank the Chinese Communist party for its efforts against the virus. This prompts huge backlash, and the Wuhan government later apologizes and retracts it.

In a Chinese magazine People interview, Dr. Ai recounts the experiences detailed above.

After Ai’s interview is published in People, China’s censors go into overdrive. The article is deleted, but netizens are faster -- they preserve versions of the story in English, emojis and even a version in a video mimicking the Star Wars opening credits.

The interview is still on Terminus 2049.

The truthtellers’ legacy

It wasn’t enough to silence the truthtellers. The Chinese Communist Party needed to create its own storyline, both to cover up its initial missteps and to deflect the reputational damage caused by China being the country where the first cases were detected.

Its first step in February was to deploy hundreds of state media journalists to Wuhan to be its eyes and ears on the ground. Although their reports were often censored, they served a dual purpose of helping to gather information for the party, something that often happens during public emergencies in China, said Mary Gallagher, the director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan and an expert in Chinese politics.

For months, Chinese government spokespeople and state media have pushed the narrative that the virus may have originated outside of China.

COVID-19 'may not originate in China' Chinese top respiratory specialist Zhong Nanshan said although the COVID-19 first appeared in China, that does not necessarily mean it originated here. #COVID19 pic.twitter.com/gk1S7XKEvh

— Global Times (@globaltimesnews) March 1, 2020

Although the epidemic first broke out in China, it did not necessarily mean that the virus is originated from China, let alone "made in China". pic.twitter.com/EVXLkQnyfF

— AmbCHENXiaodong (@AmbCHENXiaodong) March 7, 2020

By March, daily cases had fallen to double digits and much of China had emerged from lockdown. By May, China had largely controlled the virus within its own borders and its coronavirus case numbers were quickly dwarfed by skyrocketing numbers in the United States and Europe.

In the following months, China seized on that success to push the narrative it had handled the outbreak better than almost any country -- proof its authoritarian response were a model to be admired and replicated. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs dismissed criticism that it had cracked down on journalists and doctors, saying: “The Chinese government has all along conducted its Covid-19 response in an open and transparent manner.”

With the official truth scrubbed from the Chinese internet, Beijing began to fill that void with alternative timelines that painted China in a more favorable light.

The #US keeps calling for transparency & investigation. Why not open up Fort Detrick & other bio-labs for international review? Why not invite #WHO & int'l experts to the US to look into #COVID19 source & response?

— Hua Chunying 华春莹 (@SpokespersonCHN) May 8, 2020

This article is very much important to each and every one of us. Please read and retweet it. COVID-19: Further Evidence that the Virus Originated in the US. https://t.co/LPanIo40MR

— Lijian Zhao 赵立坚 (@zlj517) March 13, 2020

Officials promoted baseless arguments that the virus could have started elsewhere, including the theory US army personnel could have brought the virus to China when they came to Wuhan for the Military World Games in October 2019. In January 2021, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Hua Chunying added legitimacy to the theory coronavirus might have come from another country when she called on the US to invite the WHO to visit American sites so they could study the origins of the virus. Last year, state media seized on studies which found evidence Covid-19 circulated in Italy as early as September 2019, portraying the report as evidence the virus didn’t necessarily originate in China, despite that not being what its authors suggested.

In October, China launched an exhibition in Wuhan, featuring interactive displays promoting the idea of a heroic response to the virus. Many of the truthtellers -- including Chen Mei, doctor Ai Fen, and university professor Zhang Yongzhen -- were nowhere to be seen. The whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang was included in a wall of martyrs, but his brief biography didn’t include that he’d been reprimanded for trying to warn colleagues about the coronavirus.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and State Council Information Office did not respond to a request to explain why Chinese officials had pushed the narrative that the virus originated outside China, and whether the government was concerned that its actions could discourage doctors and journalists from speaking out about future pandemics.

A recent US CDC report found #COVID19 antibodies in blood samples as early as Dec 13, 2019. With more & more evidence surfacing about the coronavirus’ origins in places outside China before Wuhan detected it, the world is remapping the history of the #COVID19 pandemic. pic.twitter.com/0y4IRIVmFY

— Global Times (@globaltimesnews) December 2, 2020

On US Secretary #Pompeo-led hysteria-like attacks on China regarding the origin of #COVID19, Chinese FM spokesperson Hua Chunying called him “Mr. Liar” who is staging his final madness. pic.twitter.com/e7Azf2qvOY

— Chinese Consulate General in Sydney (@ChinaConSydney) January 18, 2021

There’s evidence that these efforts have been effective within China. A study published in November by international research and data analytics group YouGov-Cambridge Globalism Project found that, in nearly all countries, the vast majority of people thought Covid-19 originated in China. But in China, more than half said the virus had originated in China, while a third thought it had come from the US.

Controlling the narrative has always been important to Chinese leaders, but censorship has tightened under President Xi Jinping, and the party’s ability to communicate its own perspective has improved. “The connection the (CCP) don’t want people to make is that freedom of speech can affect not just your livelihood, but your existence,” Gallagher said. “(Controlling the narrative) is a way for the Chinese government to demonstrate that it doesn’t need to change its political systems.”

The exhibition about China’s fight against Covid-19 at a convention center that was previously a makeshift hospital for coronavirus patients in Wuhan.Nicolas Asfouri/AFP/Getty

Displays at the exhibition showing President Xi Jinping.Nicolas Asfouri/AFP/Getty

A “wall of martyrs” at the exhibition, including Dr. Li Wenliang, the Wuhan doctor who tried to raise the alarm about the Covid-19 outbreak.Ng Han Guan/AP

That isn’t just a problem for people seeking free and fair information in China -- it impacts the world.

“How many doctors are going to come out and report the next one?” said Annie Sparrow, an assistant professor of population health science and policy at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Covid-19 has killed more than 2 million people worldwide -- knowing how the pandemic took hold remains key to preventing this from repeating. China's efforts to limit free expression among journalists, activists and doctors may mean losing precious information about how the virus spread initially, Gallagher said.

“That seems very short-sighted,” Gallagher added. “This is going to happen again.”