Albatrosses walk along a plastic-littered beach in Midway. Jackson Loo/CNN

The plastic-filled stomach of a dead albatross. Jackson Loo/CNN

The smell hits you first, and catches in your throat. It's the whiff of decay, of thousands of birds' bodies rotting. Part of this is nature: CNN visited the island in June -- the time of year when the Laysan albatross lay their chicks, who must learn to fly, or die.

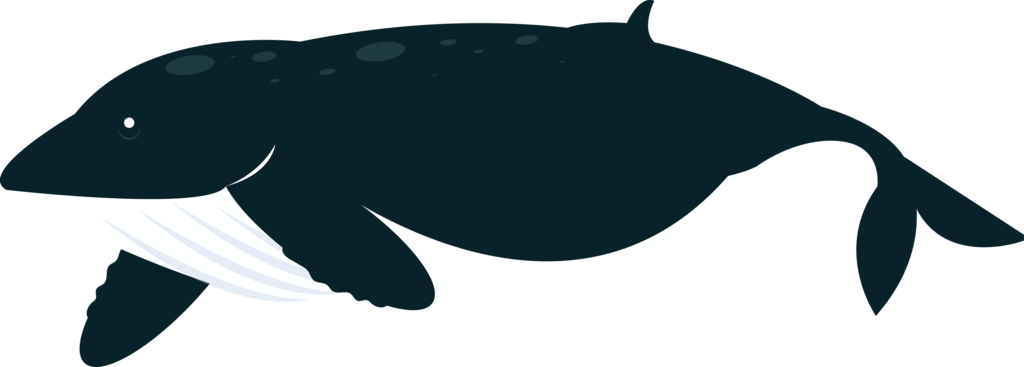

But part of it is man-made: When you tear open the fragile ribcages of the birds who did not survive -- as US Fish and Wildlife Service Superintendent Matthew Brown did in front of us -- the sheer volume of plastic waste now in our world becomes apparent.

Inside the slight skeleton of one albatross, we found bottle tops and a cigarette lighter amongst seemingly endless tiny shards of plastic. It's as if plastic actually was the bird's diet.

These brightly colored plastic fragments were picked out of the sea by the bird's parents, who mistook them for food, then fed them to their offspring. The birds can't digest the plastic pieces but they still feel full, which causes malnutrition and death, according to researchers. Volunteers here have an almost full-time job scooping up the corpses.

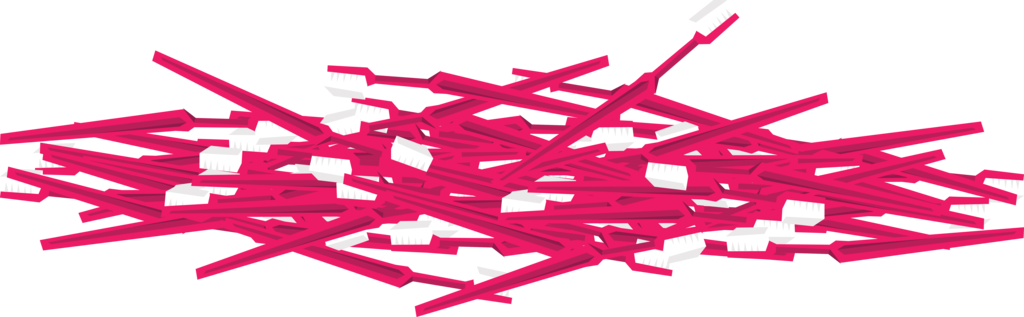

They have tried to clean Midway up; the huge dump of plastic trash sitting on the runway awaiting collection by boats is evidence of that. But it's almost impossible because so much washes ashore daily -- not to mention the five tons the birds fly onto the island inside in their stomachs each year, according to Brown.

The Eastern Island is now littered with tiny fragments of plastic. The birds die and decay, but the plastic inside them stays forever in the sand -- a layer of man's doing that will never go away. Midway will probably vanish under rising ocean levels before the plastic decays.

Albatrosses walk along a plastic-littered beach in Midway. Jackson Loo/CNN

The plastic-filled stomach of a dead albatross. Jackson Loo/CNN

"These are the classic 'canary in the coal mine' scenarios," said Brown.

"This is an animal that relies entirely on the ocean for its survival, just like 3 billion people do. If their children, their chicks, are being impacted by plastic this much, it is simply a forbearer of what is coming for us."

So much of the damage is on the edge of the invisible. If you kneel down on Midway and stick your hand into the hot sand, you can pull up a troubling multicolored array of particles.

These are what activists call the "new sand" -- plastic that has broken down into smaller and smaller pieces, and then become part of the shoreline.

Sources: Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Lisbeth Van Cauwenberghe

These smaller particles are what end up in the food chain. The smallest ones, called nano-plastics, sink deep into the ocean and can end up in plankton. Larger pieces, known as micro-plastics, float in a soup, suspended in water, and are eaten by fish. The fish then get eaten by "apex predators" higher up the food chain -- including humans, or the Hawaiian Monk Seal.

We don't know as much as we want to about what plastic has done to these seals -- they're endangered, so there are restrictions on opening them up for study by scientists. But there are already troubling signs.

Jessica Bohlander, a marine biologist from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, says the seals are acting as a "sentinel for exposure to plastics and other persistent organic pollutants for humans."

"A few individual animals we have seen have very high levels [of micro-plastics], particularly in adult males," she said.

Bohlander says plastic ingestion could be causing reproductive problems for the seals -- and the bigger the animal, the bigger the concentration of plastic.

"It is very troubling," she said. "With every step of the food chain, the concentration that can be measured in the tissues of animals becomes magnified."

Seafood is essential to human life, but there is growing evidence that fish may prefer eating plastic to food.

Swedish scientists recently demonstrated that larval Perch raised in waters containing micro-plastics "only ate plastic and ignored their natural food source of free-swimming zooplankton."

This diet of plastic stunted growth rates, reduced hatching rates, and caused abnormal behaviors in the young fish, according to the study.

There's also evidence that plastic is harmful to humans. The US government says styrene -- one of the key ingredients in plastic -- is probably a human carcinogen. It is studying the effects of plastic litter on marine life and plans to launch an inquiry into the effects on human health, including fetal formation.

One study found that man-made marine debris may cause "physical harm" to humans when ingested via seafood. Another estimated that Europeans who eat shellfish could be exposed to 11,000 pieces of micro-plastic each year.

What science hasn't proven yet is whether the plastic in the fish we eat directly damages our health. But it's getting there, and the case for real government concern is growing.

And Midway, just by dint of its own distance and damage, is making that case.

Matthew Brown told me he eats sushi much less than he used to.

"Plastics also attract other contaminants, so if you are eating food that has little bits of blue and red in there, these are attracting ... other contaminants in the ocean. This has a real impact on our primary food source."

We took a boat out from the island, towards the coral reef that surrounds it. There, you can feel the awesome power of nature.

Caught in the reef nearby was a sight far more troubling than the bottles we had seen float past us on the water. In one inlet was a soup of tiny white pellets. A huge piece of Styrofoam packaging had been caught, now bobbing and slowly breaking down. In its thick soup was a bottle-top, a feather, and other gunk. You could swim into it easily, let your head emerge up in its midst.

Signs of resilience and defiance in nature abounded, but in one corner, man's carelessness had occupied a visible space and, perhaps for longer, an invisible one. We simply do not know what we have already done.

The hardest part about the journey to Midway is the sense of powerlessness it leaves you with. The damage there began with choices -- and litter -- made decades ago. And the problem is growing, not shrinking, as humanity gets more environmentally aware.

Stopping this flow of trash would require an incredible change in the daily behavior of 7 billion people.

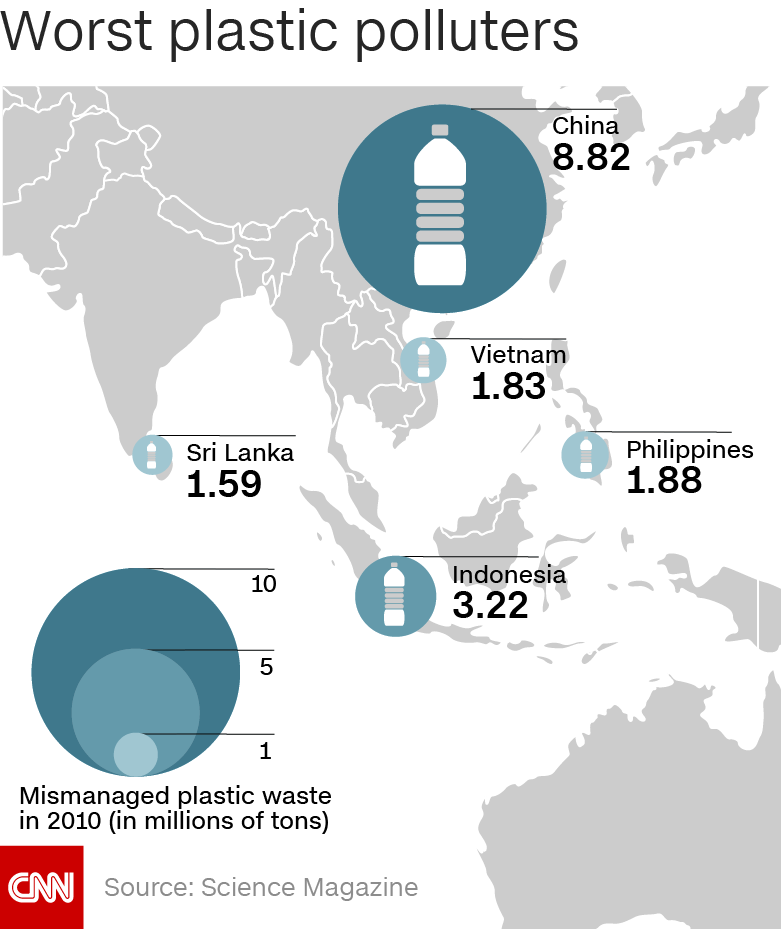

China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Sri Lanka are considered the five worst offenders when it comes to plastic pollution, according to a study published in Science, and you can anticipate as much success telling people there to stop using disposable plastics as you would do in the US. Road test the phrase: "I'm sorry, you can't have that coffee as you haven't brought your own reusable cup."

So what can you do? Very little, unless we all do it. You can start by bringing water bottles to work, or a reusable fork to the café, or insisting on less packaging for products.

For now, the balance of convenience versus the likely risk to human health is in the favor of the coffee cup. If the science isn't there yet, public opinion won't be either.

There is a tiny glimmer of hope amidst this looming disaster, one I often heard while talking to researchers, one that shows people can change.

It's a recent example of something so glaringly, obviously bad for the planet -- and people -- that for centuries was accepted as a normal part of our happy, modern world.

Remember smoking? We don't do that as much anymore.

CNN's Nick Thompson, Kenneth Uzquiano, India Hayes, Sean O'Key and Lauren Said-Moorhouse contributed to this report.