Cover photo: DigitalGlobe

Editor's note: CNN columnist John D. Sutter is reporting on a tiny number -- 2 degrees -- that may have a huge effect on the future. He'd like your help. Subscribe to the "2 degrees" newsletter or follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. He's jdsutter on Snapchat. You can shape this coverage.

Majuro, Marshall Islands (CNN)

Angie Hepisus heard her nephew, Mark, banging on the door and screaming in Marshallese.

"It's flooding! It's flooding! Get out!"

Her thoughts went immediately to her family on this fragile coastline in the middle of the Pacific, a place under increasing threat from climate change.

One of her cousins woke up that morning last spring to find herself floating, her plywood home filling up like an aquarium. Another, who lives in a house where the roof is held down by evenly spaced rocks, was so bewildered by the rush of water that had invaded her house at 4 a.m. that she actually licked her arm to be sure that, yes, this was saltwater, and, no, she wasn't having a nightmare.

Then there was Jitiam, her wild-haired nephew, who was trying to tie his family's pigs to a tree trunk to prevent them from washing away. And Roselinta, who was sleeping with her 2-year-old son, Shiro, in a house that was being carried inland by the storm and the unusually high tide that accompanied it.

"My mind and my heart were pounding," Angie told me.

"It's like: not again."

She grabbed the Bible and all the family members she could.

They waded out into the dark.

Out here in the middle of the Pacific, somewhere between Australia and Hawaii, there's a place where no one has the luxury of denying the existence of climate change. People here in the Marshall Islands are living it. Have been living it.

They've internalized the gravest of predictions -- that the Marshall Islands, this loose collection of no-elevation coral atolls, likely will be submerged beneath the waves as humans continue to warm the atmosphere and the oceans continue to rise. They've seen their homes flood frequently -- seen the tides getting higher, seen their lives threatened. Mojje Anungar watched the remains of his infant son, George, who died at 7 months, wash into the Pacific from a coastal graveyard.

Video: Climate migration

"I'm still shell-shocked," he told me through an interpreter. "Before, this kind of thing never happened."

A few people already are making the difficult decision to leave this country, in part because of the frequency of floods and the threat of climate change; and I found some of them seeking refuge in the most unexpected of places.

In the nine days I spent in Majuro, the crescent-shaped capital of the Marshall Islands, I learned there is nowhere on these islands to escape the floods. People, I was told, seek shelter on the second stories of buildings, or by climbing up the trunks of coconut trees. The only "hill" to speak of in Majuro is a bridge that's built over an inlet.

Perhaps nowhere is the precarious nature of this country's geography more apparent than Rita, a crowded neighborhood at the very tip of Majuro. That's where Angie and her family live, where they faced the "inundation event" last spring.

"I don't think these islands are going to last that long," Angie told me.

Disappearing country, disappearing stories

I documented my journey to the Marshall Islands on Snapchat, which is a social network for disappearing stories. Below you'll find a few examples of what will be lost if this country is submerged by rising seas.

"Once a big tide comes, we're all going to be washed away."

For Angie and her family, the March 2014 storm felt like the beginning of the end -- like the ocean, always an ally and friend, finally had turned on them.

'Seeing is believing'

It's disturbingly easy to write off a country you've never seen.

I didn't realize that until I visited the Marshall Islands -- until I watched five hours of sapphire ocean pass beneath my airplane window between Honolulu and Majuro, completely unable to pull my eyes from the wet infinity below.

No boats, no land. Only water -- salt-speck waves cresting on a backdrop of blue; clouds casting coffee-stain shadows on the surface of the Pacific.

I felt my chest tighten up.

All this nothing.

Where was this freaking place?

The answer offered little comfort. Majuro appeared as a delicate necklace of land draped around a turquoise lagoon -- some of it barely wider than an airport runway. I'd read plenty about the Marshall Islands before hopping on a plane in Atlanta 31 hours earlier. But none of it prepared me for the sight of this tiny little atoll -- this coke-line of sand and palm -- tossed out in the middle of the terrifying sea.

No wonder this place is at risk for climate change.

It's barely treading water.

I embarked on this journey to the middle of nowhere because CNN readers voted for me to look into "climate refugees" as part of my Two° series on climate change. That idea came in the form of a question from Kelly, a 48-year-old reader in San Jose, California, who asked, "What happens if thousands or tens of thousands are displaced due to rising sea levels or desertification? Where do they go?"

More than 11,000 voted in a poll that commissioned this story.

As the results came in, I started searching for a suitable case study. There are countries like Bangladesh where millions likely will be displaced by rising seas. But Alice Thomas, from Refugees International, drew my attention to low-lying island nations that could vanish if seas rise as much as 1 or 2 meters.

Kiribati, the Maldives, the Marshall Islands.

All of these barely peek out over the surface of the ocean.

And all of them literally could be wiped off the map.

That's not an immediate prospect -- definitely not five years or 10. Even 20. But it could happen within our lifetimes, and certainly within the next generation's.

Scientists say we easily could warm the atmosphere by 2 degrees Celsius by the end of the century -- and if you call up a scientist like Stefan Rahmstorf, a professor of ocean physics from Germany's Potsdam University, he'll say ominous things like this: "Even limiting warming to 2 degrees, in my view, will still commit some island nations and coastal cities to drowning." In other words: See ya, Marshall Islands.

The tone is almost nonchalant.

Not because he doesn't care; he does. But because he says this stuff so often -- and I hear this stuff so often -- that it almost starts to seem expected. Easy to intellectualize. As if an entire country, culture, history and language are logical externalities of our fossil fuel addiction. Oh yeah, drowning islands. Heard that story.

It's quite another thing, however, to walk down the tarmac in Majuro.

There you see the broken sea wall, crumbled by floods that, in recent years, covered the runways and shut down the airport temporarily. You see sand piled up along the road, as if pleading with the ocean to stay back. You feel the thick air, warm silk on your skin. You wipe the fog off your glasses. And you take in the sweet smell of the ocean -- all brine and crab and palm frond.

If you're lucky, you meet Amatlain Kabua, a Marshallese princess, former ambassador to the United Nations, and daughter of this country's first president. She met me at the plane -- threw a lei around my neck, a loop of fragrant yellow flowers she picked herself. She welcomed me with a Marshallese word that is as ubiquitous as it is magical.

Iakwe.

Meaning: "Hello," "I love you," and "You are a rainbow."

How could you not love this place?

Amatlain insisted that I sit down, have some coconut milk (right from the coconut, but with a straw, because, well, this is 2015) and hear about her country's "existential fight" to convince the world that this place, these people, exist -- and that they matter enough to blunt the force of climate change.

Climate change is real, she said.

"Seeing is believing."

I'd learn she was right.

Because, when you're standing all the way out here, you have to wonder: How could this place -- this charming, sweaty, smelly place -- vanish?

Or, more accurately: How could we make it vanish?

'The melody of it has changed'

The biggest flood was more than a year ago but she still doesn't sleep.

Is it high tide? King tide? Any chance for a swell?

Angie Hepisus checks tide and weather apps constantly, and wakes her husband, Timothy, to be sure she hasn't missed something critical.

Outside, the ocean laps at the land -- only paces from her bedroom wall.

She hears it out there, churning like a washing machine.

She's not able to let her guard down, unable to find peace.

"The sound of the ocean, it (used to put) me to sleep. It's like my lullaby," Angie told me. "Now, it's more like slamming and hammering. It's so noisy. It scares me at night. ... It's changed. The melody of it has changed.

"It's not the same song I used to love."

The 44-year-old grew up in the teal concrete house at the edge of the land -- she, her 16 siblings and their parents, all living under one roof. Marshallese families aren't bound by terms like "nuclear," so it isn't uncommon for a gaggle of cousins, aunties, nephews and great uncles to live together as well. It makes sense when you know how the land -- the precious little land -- is handled. All of it is owned by several chiefs, and it's managed on behalf of the family community. People here mostly don't pay rent; they ask for room to build on the family land and it's granted, free. Land rights are passed down from a mother to her children. So this plot of land on the coast in Rita is not just any place; it's a family heirloom, a part of their identity.

Ukulele music is everywhere in the Marshall Islands. The instrument here has three of the usual four strings.

Angie is the third youngest of the 17 children, and the youngest girl. But she's the acting matriarch, ensuring that dozens of family members, many of them living on this precarious stretch of coastline, are fed, clothed and kept safe. She's also the family historian, safeguarding and updating documents pertaining to the family's royal heritage and their land here in Rita and elsewhere.

These are her responsibilities for perhaps three reasons. First, she's bossy as hell. As a kid, Angie's siblings nicknamed her "big eyes" and "reporter," because she saw what other family members were doing wrong, and was quick to tattle. Her world is one of right and wrong, and she'll certainly tell you if you're wrong. Second, she has arguably the best, most stable job of her siblings, working as an executive assistant at the Bank of Marshall Islands in Majuro. And, finally, and most importantly, she's here.

The others are not.

The house where Roselinta and her 2-year-old lived before the flood? What remains is a slab of concrete. Mark, the nephew who woke her as the waters were rising? Jitiam, who was trying to tie up the pigs before they washed away?

They are gone.

'We are not a small island country'

I spent much of my time in the Marshall Islands trying to figure out what will be lost if we let this country drown beneath the rising ocean. I decided to document these wanderings on Snapchat, an app for stories that vanish after you view them.

I called them disappearing stories from a disappearing country.

Annoyingly meta, I know.

A premise for my findings: To really get the Marshall Islands, you need to understand that this is a country that's far more water than land. The total area of the country, including the Pacific Ocean, is nearly three times that of Texas.

Subtract the ocean and you're left with land that would fill Washington, D.C.

"We are not a small island country. We are a big ocean country -- with a conscience that we'd like to share," said Tony de Brum, the foreign minister.

The first people are thought to have arrived in the Marshall Islands 2,000 to 3,000 years ago, likely coming by canoe from Southeast Asia. Think about that. A voyage across the Pacific by outrigger canoe. That's the kind of thing that just doesn't happen in the SpaceX era -- well, unless you're Alson Kelen, director of a nonprofit called Waan Ael?? in Majel, or Canoes of the Marshall Islands.

I met Alson, a smiley 47-year-old who looks like the surfer-dude version of George Foreman, at his canoe-building workshop on the Majuro lagoon.

Outside, a couple dozen young men were hacking away at a breadfruit tree, turning it into a vessel. They were planning a 200-mile voyage out to sea -- which is nothing for Kelen, who has ridden outrigger canoes from the Marshalls to both Hawaii and New Zealand, a trip where the sun blistered the bottoms of his feet.

"A lot of people navigate with their heads," he told me, sitting in his office, a stick-and-shell map of the currents of the Marshall Islands nailed to the ceiling above us. "We navigate with our stomachs. We feel the swells and we know where we are."

Alson doesn't want to brag about these feats and is quick to say he's not a "master navigator." His expertise, he insists, is the art of canoe building.

For details, he deferred to the experts.

"By lying on his back in the bilge of his canoe and sensing the motion of the canoe, the skilled pilot can 'fix' his position at night even without looking at the sea, for the movement of the canoe alone will tell him what kinds of swells are acting on it," wrote University of Pennsylvania anthropologist William Davenport, in 1964.

This strange skill is especially incredible -- and necessary -- when you consider the Marshall Islands are so low to the sea that they're basically invisible from a distance.

To know where an island is, you have to feel its presence.

That takes work, so training for "master navigators" starts in early childhood, said Joseph Genz, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Hawaii in Hilo. The youthful trainees are placed for hours at a time in mini-canoes and floated out onto the water so that they can tune their stomachs to the waves.

"This knowledge is very sensitive," the professor said by e-mail.

It's also exceedingly rare these days. Alson, however, hopes to bring back the art. He's already training dropouts to build canoes. And, one day, he wants to help them learn to navigate their oceanic nation.

He told me he'd be the last person to leave these islands if they sunk beneath rising seas -- that he'd be out here after everyone else, treading water.

But he also sees this training as an insurance policy.

If these kids have to abandon their country, at least they'll have some skills.

Maybe this piece of their heritage can survive.

Or at least they'll know it existed.

'Adios Marshall Islands'

In Majuro, ask anyone -- from Angie and her family to kids you find playing basketball on the street, using plastic buckets for hoops -- where they would move if the islands keep flooding and you tend to get one of three answers: Hawaii, which makes sense because it's close-ish, and it's also a collection of islands; Washington state, which is freakishly cold compared to Majuro, but, still, is on the West Coast.

And then: Arkansas.

Springdale, Arkansas, to be exact.

I was so perplexed that I decided to pay a visit to Springdale.

It's a woodsy town of rolling hills, blinking strip malls and taquerias.

Hundreds of miles from an ocean.

As landlocked as they come.

"It's the largest Marshallese population in the continental United States," said Carmen Chong Gum, the consul general of the Marshall Islands in Springdale.

Yeah, let me repeat that. The government of the Marshall Islands has an official consular office in Springdale, Arkansas. It shares a building with a barbershop, an attorney and a gadget repair store called Undead Electronics.

The population there is so sizable that I met a candidate for Marshallese senate, Tadashi Lometo, who was making a campaign stop in town.

"If you win in the States, you will also win back home," he said. "We have a large community here in Arkansas."

How large is what's incredible, though.

The Marshall Islands is home to about 70,000.

There are 10,000 Marshallese in Northwest Arkansas, according to the consulate.

Ten-thousand people. Nearly 15% of the country's population.

And they vote by mail.

Photos: Life in the Marshall Islands

Kids on the street in Majuro, Marshall Islands, in the remote Pacific, can tell you anything you want to know about climate change. They know the seas are rising. This basketball court is next to the foundation of a house destroyed in a recent flood.

Marshallese people are known as master canoe builders and navigators. Including the ocean, the nation is three times the size of Texas. But it only has as much land as Washington, D.C. "We are not a small island country," said Tony de Brum, the foreign minister. "We are a big ocean country."

Rositha Anwel, 22, said she woke up to find herself floating during a March 2014 flood. Some neighbors moved away, but Anwel can't imagine leaving her family's home on the water. "This is where I grew up," she said.

The kemem, or first birthday party, is an important rite of passage in the Marshall Islands. These celebrations often are larger than weddings, and hundreds can attend.

Waves crashed over this home in Majuro during a recent flood, according to residents. Some say they want to leave this precarious spot but don't have the money to do so.

The Marshall Islands lives in a delicate conversation with the sea. The Pacific Ocean brings life and food, but lately some residents have started to fear the rising tides.

Angie Hepisus recently buried her brother, one of 17 siblings, behind her home on the coast in Majuro. Other nearby grave sites on the island have washed away during floods.

Wina Anmontha says her daughter, Roselinta, moved from Majuro to the United States in part because of fears that floods are becoming more common here.

The Marshall Islands is an independent country but uses U.S. currency and has a contractual relationship with the United States. Marshallese people can live and work in the United States without a visa.

Reef fish, breadfruit, rice and pandanus fruit are the staples of a traditional Marshallese diet. Junk food and soda have become common, too, and obesity rates are high in the islands.

Angie Hepisus and her family said they decided not to repair this house after it was damaged in floods. Land in the Marshall Islands is managed communally by chiefs, so families often live in clusters together.

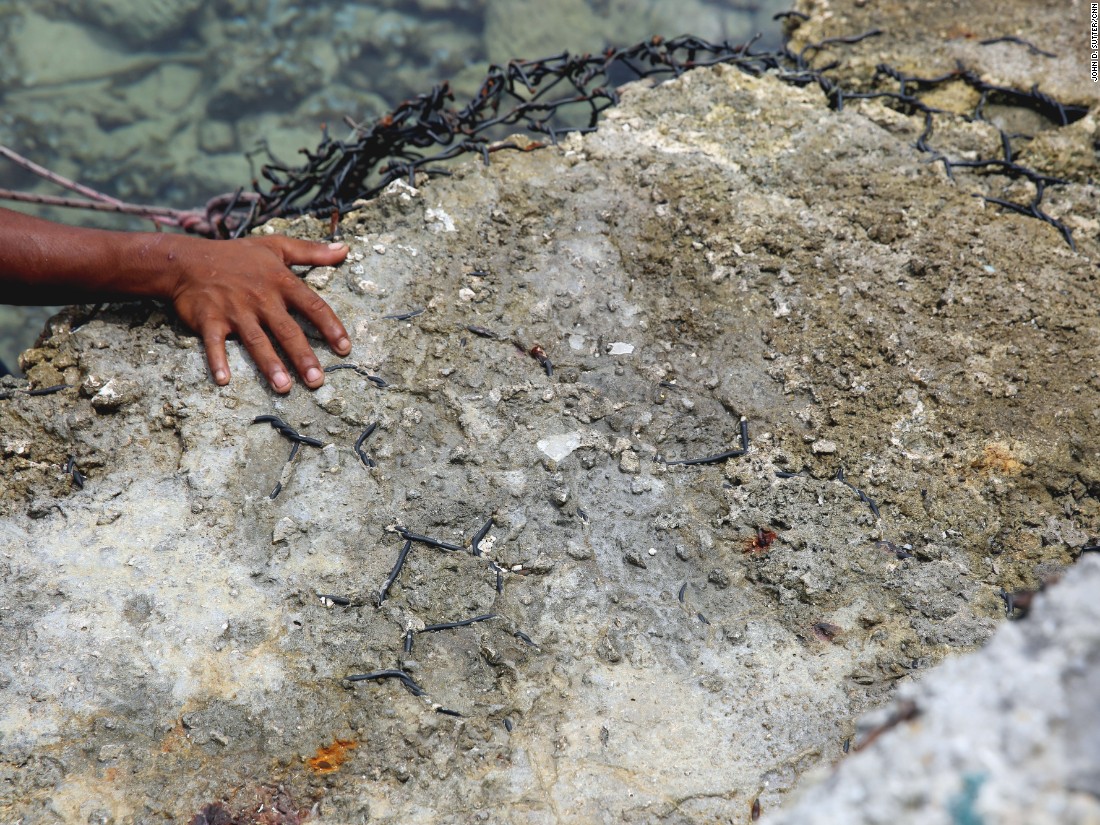

When floodwaters rush in, residents say they tie their animals to trees to try to keep them from disappearing into the Pacific Ocean.

Emi Anwel, 20, woke up to find water in her home during a recent flood. She licked her arm to be sure that, yes, the water tasted salty. That's how she knew the ocean was coming for her.

Flooding is only the most obvious impact of sea level rise. Trees and crops along the coast die when they're saturated with saltwater. Supplies of freshwater also become contaminated. Some researchers say the islands likely will become uninhabitable long before they're submerged by rising sea levels.

So, how did they end up here?

Run around town asking that question and you'll get one name: John Moody. I couldn't wait to meet him -- to find out how this all happened.

But there's a problem, several folks told me: John Moody's dead.

One woman was so sure of this that she pulled up John Moody's tombstone on Google Images when I told her I was trying to find him.

But it turns out John Moody is not dead.

Just in hiding.

After engaging what felt like half the Marshallese population of Springdale, I tracked down John Moody -- blood in his cheeks and living about an hour and 20 minutes by car from Springdale. He's situated on top of a hill, in a beige double-wide trailer. Buzz cut and policeman mustache. Thirteen chickens running around out back.

He keeps to himself, he told me, because he's so well-known in Springdale that people stop him at traffic lights, yelling, "Hey! John Moody!"

It's the price you pay for being the original Marshallese in Arkansas.

"That's what they call me," he said. "Pioneer."

John, 63, moved to the United States from the Marshall Islands in 1979 -- before the frequent flooding that Angie's family is now experiencing, but around the time that seas started rising because of a stark uptick in fossil fuel emissions. His first stop: Oklahoma, where he went to school on a recommendation. He got a summer job at a chicken processing plant and decided he liked that better. The work led him to Springdale, which is where Tyson and other poultry companies are based.

Soon, he had 13 or 14 relatives living with him -- all working on factory lines, dissecting chicken parts with knives for wages unthinkable on the islands.

"I said, 'Adios, Marshall Islands, I'm gone,'" he told me, smiling.

Throngs of migrants followed, many looking for work or better schools for their children -- a chance to learn English. Marshallese people can live and work legally in the United States without a visa because of the Compact of Free Association, which allows the United States to keep a military base on one of the atolls. (It's hard not to see this as more of a system of reparations for nuclear testing than as a favor to the islands, by the way. Starting after World War II, the United States detonated nuclear weapons on some remote atolls in the Marshall Islands, relocating entire populations and exposing others to cancer- and disease-causing radiation.)

Now, however, a new wave of migrants is emerging: Those, like Angie's family members, who worry their nation will be flooded.

Roselinta, Mark, Jitiam, Shiro.

You may have guessed it.

I met all of them in Arkansas.

Roselinta, who was living in the shack that floated away during the March 2014 flood in Majuro, told me she likes life better here. She lives in a second-floor, three-bedroom apartment with 10 family members. A dozen or so pairs of flip-flops are stacked up just inside the door. The apartment's walls are covered in family photos and flowers made from coconut husks and dried pandanus leaves.

I asked Roselinta what she liked so much about this place.

Her answer surprised me.

It's far from the ocean, she told me through an interpreter.

And that means it's safe.

'In God's hands'

In trying to understand this "big ocean country," I figured I needed to get out on the water. Fortunately, Alson Kelen, the canoe guru, offered to give me a lift.

We didn't go far -- just across Majuro's kidney-bean lagoon -- but even that short journey was revelatory. Majuro essentially is one road, but if you're driving up and down it day after day, dodging kids and roosters that weave in and out of a steady stream of traffic, you start to forget just how isolated this location is, how fragile.

From the water, however, the land vanishes.

The outrigger landed on Ejit, a tooth-shaped island with no cars or roads. I roamed around with a resident-slash-security guard, David. He walked with a heavy limp and wore a thick beard, even though it's always sweat-through-your-T-shirt weather here.

Most residents of this island came originally from the Bikini Atoll, he told me. They were relocated a number of times after the United States conducted nuclear tests on their remote islands. A hydrogen bomb 1,000 times as powerful as those dropped on Japan during World War II was exploded on Bikini Atoll in 1954, after the war.

As testament to this awful history, I saw young children running around with Ejit Elementary School T-shirts that featured cartoons of that nuclear blast on the back.

The text, translated from Marshallese, read, "Everything's in God's hands."

Or: The hands of the bomb makers, I thought.

Eventually, I sat down beneath a breadfruit tree -- with its leaves as long as a forearm and its starchy fruit -- to talk with Ken Amlek, a 23-year-old with piercing, raven eyes, whose family originated in Bikini. He explains its long, dark history in a yep-that's-how-it-is simplicity: "They tested the bomb, and that's why we're here."

Angie Hepisus, 44, says the sound of the ocean once was her lullaby. Now, it scares her.

Now, he said, this island, which he and his family never liked to begin with, is flooding frequently. The land is curved like a bowl, and it fills up at the center with saltwater, he said. He wants the United States to pay to relocate him. You could see a move as a form of climate change reparations, similar to the $604 million the United States has spent trying to make up for the nuclear tests, which not only evicted people from their ancestral homes but also were linked to cancer.

To date, although China isn't far behind, the United States is the largest aggregate polluter of carbon dioxide. So why not hold the United States liable?

Maybe climate change is the new nuclear testing.

Slow moving, and less intentional.

But just as threatening.

I must say this argument started to work on me when I was on Ejit.

Partly that's because Ejit is a place wedged between worlds. I saw girls playing checkers with rocks on a carved-out table -- while a friend tapped at her iPhone. There's no running water and limited electricity in some homes. Ken showed me the rain catchment tank he drinks from, and it was full of pinkie-finger-size fish, which he said are there on purpose because they eat the mosquitoes. When the tide's low, though, you can walk across the coral reef to Majuro, where there's an airport, hospital, restaurants and a handful of Wi-Fi hot spots. Life on Ejit, and especially the remote "outer islands" of this country, is hard. Leprosy remains a scourge, obesity rates are high, access to medical care inadequate.

Maybe the solution is to shove this country into the climate-changed future -- to accept the realities now, and deal with them accordingly. There's no international law to protect would-be "climate refugees," Walter Kaelin, envoy of the chairmanship of the Nansen Initiative, a group that focuses on climate change and migration, told me. They can't seek asylum in other nations -- or haven't been able to. A man from Kiribati, according to news reports, tried to seek asylum as a climate refugee in New Zealand. The courts rejected him. And while people from the Marshall Islands can live and work legally in the United States, refugees from Kiribati or the Maldives, for example, would have nowhere else to go, legally, if their island nations disappeared. As a Plan B, Kiribati reportedly purchased more than 5,000 acres in Fiji. Academics who study this sort of planning tend to say it's healthy. They call it "migration with dignity." Rather than a desperate flood of refugees.

Some island nations "want to be able to choose when to go," said Walter. "They want to be able to choose more or less where they go.

"In that sense they want to remain masters of their own destiny."

Think of it: A planned exodus before the country disappears -- before freshwater supplies get tainted with salt; before saltwater intrusion kills all the fruit trees; before floods are so frequent that people have no choice but to try to move away.

I started to think, maybe Ken Amlek is right -- maybe the United States should pay, now, to relocate anyone from the Marshall Islands who's willing to leave. A one-way flight from Majuro to the Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport goes for $1,600 at the moment, when reserved one month in advance. (Duration: 33 hours. Stops in Honolulu, San Francisco and Houston.) Some families save up for a year or more to make that trip. Others, like Angie's cousins living in plywood-and-tin homes, seven or more family members crammed into one room, never could do that.

Based on that fare, it would cost $84 million to fly every Marshallese person to Arkansas. Maybe we should provide the funding, make this thing orderly.

Face the issue head-on.

Establish the New Marshall Islands.

Location: Springdale.

'You have to hold them'

On first glance, the islands have nothing in common with Arkansas.

Just look at Angie's family's arrangements.

In Majuro, they live in a small cluster of homes along the coast, three pandanus trees planted out back because their roots run deep and supposedly hold down the soil. When the leaves rattle in the ocean breeze they sound like rain. Sunsets electrify the clouds, all pink and orange, and a full moon makes the water shimmer at night.

Smiley ukulele music is almost always within earshot.

Compare that with Arkansas, where you climb a gravel staircase to reach the second-floor apartment. Inside, curtains are drawn all day and the lights are always out, in part because half the family works the night shift at the chicken packing plant, and because they're trying to save electricity. On the few days I spent time there, most people seemed to be watching TV or playing video games. They don't eat together because of their opposite schedules. Dinner's often ramen.

In the Marshall Islands, it would be rice and reef fish, served whole, the eye staring at you (Angie got onto me for cringing about the eye, and for apologizing to a fish before I peeled its skin off). Breadfruit and pandanus, a mustard-colored fruit that tastes like a mango merged with an avocado, are Marshallese staples.

There's a Marshallese grocery store in Springdale, but it's stocked only when the owner takes trips to the islands, bringing the merchandise in a cooler that she checks on the flight. The shelves are half-empty, and the store doesn't carry breadfruit or pandanus. They rot, a clerk told me, and there's not enough demand.

Look harder, though, and there are similarities.

Take religion. Almost everyone in the Marshall Islands is Christian. Angie and her family are Seventh Day Adventists, and there are churches for them in both locations. I'm told, actually, that there are more than 30 Marshallese churches near Springdale -- all of them offering services in the Marshallese language.

Then there are the big-little things, like sleeping arrangements. Many of the family members in the Marshall Islands sleep on thatched mats, rather than mattresses, but in both places the families sleep stacked next to each other. In the Springdale apartment, kids sleep in a room where three mattresses are arranged side by side.

"I'm used to sleeping with my children and my nieces, my nephews" on the same mattress with me, said Cynthia Riklon, 45, Angie's sister, who's living in Arkansas.

"You have to hold them."

Especially when they're so far from home.

There's an intense sense of longing hanging over Springdale.

First birthday parties, or kemems, are often bigger than weddings in the Marshall Islands.

That's especially true for older generations. Take people like Cynthia, who never left the Marshall Islands until she came here. She wouldn't have done it, she told me, if not for her kids. The Marshall Islands, especially with the floods, was no longer safe for them, she told me. When they're grown up -- when they've finished school and don't need her so close -- she wants to move back to the islands.

But her kids -- she wants them to put down roots here, where it's safe.

People like Cynthia do little things to hold onto what makes them Marshallese. I met Rumina Lakmis, from the Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese, sitting at an office desk in the building that houses the consulate. Flip-flops are that line for her. "During the cold winter, you see the American people all cuddled up with their scarves and sweaters and things," she said. "And me? I wear my flip-flops all winter. See?" she said, pointing down to her feet. "It's my Marshallese culture. ...

"I don't feel Marshallese if I wear boots."

I met another Marshallese man in Springdale, Edison Maddison, 44, who told me he lies on the floor at night with all the lights off and stares at a small aquarium in the living room. A blue-cheeked fish swims in circles, illuminated by a single bulb.

The sight transports him back to the ocean -- back home.

I tried to bring a piece of the islands back with me, too, in the form of a video clip of Angie and her family in Majuro, standing on a sea wall they constructed after the March 2014 flood. It's twilight -- dark enough I had to shine a spotlight on the group to get their images to show up on camera. I promised them I'd show it to their stateside family members. John, Angie's nephew, plays the ukulele.

Angie chose the song: "God bless Marshall Islands."

It's a farewell tune, I'm told. Appropriate for a funeral.

You see all the trouble going on

Things not getting better; but they're getting worse

God bless Marshall Islands once again.

It's a plea, in a sense.

See us, God?

We're down here, too.

Two first birthdays

A child's first birthday, or kemem, is perhaps the most significant celebration in the Marshallese culture. These parties are bigger than weddings. Historically, many infants did not live through their first year -- never reached maturity.

So a kemem is a rite of passage, and a celebration of survival. A hope for longevity and happiness.

I was fortunate enough to be invited to kemems in Majuro and Springdale.

In Majuro, I walked down an aisle of tiki torches with Angie, Timothy and their cousin, Darrell, to find one of the most joyously random scenes I've encountered: Some 500 people eating, singing and dancing in a courtyard on a tropical evening. There was a banner featuring three photos of the baby intermixed with those of unicorn ponies, a cake with an icing portrait of the 1-year-old, a cupcake tower, two bands, and tubs of rice so big two people had to carry them.

Plus, a chief. Looking very "Godfather."

It was easily the most lavish birthday party I've attended -- and, it's been a while, but I'm pretty sure it would compete with some episodes of MTV's "My Super Sweet 16." I mostly spent my time there running around collecting photos and video clips, but, at one point, the (very kind and happy-to-be-photographed) family of the 1-year-old insisted I sit down to eat. And they didn't want me to eat just a little bit.

They wanted me to eat a tray of food as wide as a beach ball.

Angie's cousin, Darrell, helped me identify what I didn't recognize. Here's what we spotted, organized into two or three layers, with rice and spaghetti on the bottom: sea turtle (grilled), pandanus fruit cooked in coconut milk, sushi, sashimi (fish here often is consumed raw), fried chicken, spare ribs, coconut meat, potato salad, parrot fish, grilled breadfruit, grilled pumpkin cooked in coconut oil, breadfruit cooked underground, fresh breadfruit (so much breadfruit!) fruit salad, fried noodles, turtle intestines, boiled banana -- and a hot dog.

Again, all on one "plate."

I sat there for a minute, picking at the food, and watching dancers in matching floral shirts squat and twist and pump their arms, as if doing push-ups in the air. I smelled the sweet, heavy air, felt the sweat on my skin. Saw the lights dangling from the breadfruit and pandanus trees, the 1-year-old clapping and cooing as people lined up to put $1 bills in her pink, inflatable swimming pool. I couldn't imagine all this -- this celebration, this hope for a 1-year-old child's bright future, this food, this party, this land, this life, the nation -- vanishing beneath saltwater.

Land is identity in the Marshall Islands.

What happens if the land is gone?

The Arkansas kemem took place at an indoor event space next to a Demolition Derby at the Rodeo of the Ozarks. I saw two Marshallese kids standing at the fence, fingers wrapped around the chain links. Car engines roared under the stadium lighting.

Going to the kemem? I asked.

"No."

They were transfixed by the cars.

Inside, the air conditioner was set to 68 degrees Fahrenheit, and a mechanical breeze fluttered balloons affixed to banquet-style tables. The room had a pitched roof and concrete floor. Portraits of white guys in cowboy hats adorned the back wall. There were about 100 people, some in traditional Marshallese dress -- floral prints, headbands, flip-flops. Others wore jogger jeans and high-top sneakers.

Yeah, there were a variety of foods.

But chicken seemed like the main course.

And only one kid danced.

I talked to several people about the steadily increasing migration of folks to Arkansas. Do you think it will pick up as climate change continues?

What do you think will happen to the islands?

"There's always Arkansas!" said Mahku Moghaddam, 24, offering a consolation to the sinking nation. "They're all welcome here."

Many of the Marshallese people came here, of course, for better jobs, better schools, better lives. Those were factors for Angie's family who moved here, too, on top of the floods. I don't begrudge them any of that. But I worry this is a window into the future -- a future when many Marshallese people will be here not because they choose to be but because they have to be. Because their country no longer exists.

Standing there in landlocked Springdale, I thought of Angie and her family on the coast in the Marshall Islands. They're considering leaving their country, too, and for a mix of reasons, as is always the case -- partly the floods and partly their family in the States. But they would hate this event, I'm sure. No breadfruit, no pandanus.

Air conditioners give Angie the chills.

In the back of the room, I chatted with three teenagers who had headphones jammed in their ears and smartphones stuck to their faces. I asked a kid in a Chicago Bulls hat what he thought about climate change. "It's all right," he said, in that yeah-whatever, SNL-parody-of-Justin-Bieber sort of way.

Like, sure. Who cares?

Not my problem.

Or, more accurately: Not my experience.

'I'm not going to entertain that question'

I have a confession to make: Maybe I'm the worst person to be telling you the story of the Marshall Islands. I'm from a country -- the United States -- that is helping raise sea levels worldwide and that conducted nuclear testing here. I flew on a plane to get here -- emitting 2,682.33 pounds of carbon dioxide in the process, and that's just one-way. I grew up in a state, Oklahoma, represented by Sen. Jim Inhofe, one of the country's most vocal climate skeptics. He recently brought a snowball -- a snowball! -- onto the U.S. Senate floor to show that, no, obviously global warming isn't happening. I mean, lookie here. There's snow.

Such buffoonery is so shameful. I felt embarrassed to be in the Marshall Islands asking people questions about where they'd move.

I was glad when someone finally pushed back.

"When people ask that it feels like defeat," Mila? Loeak, a climate activist who also happens to be the President's daughter, told me, very matter of fact. "And I don't want to feel defeated. I don't want to entertain that question. I think people should be saying, 'What can we do to help?' instead of saying, 'When will you go?'"

Or where will you go.

I have to agree with her.

If you bundle up all the Pacific countries, they contribute 0.03% of global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels, according to a study cited by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

These islands aren't causing this problem.

And because of that, they're powerless to save themselves.

'Not yet underwater'

The Marshall Islands is a place of stories.

Passed down by word of mouth so they won't disappear.

During my brief time in the islands, I met people like Angie who are witnessing climate change and who are trying to do what's best for themselves and their families. By sharing their stories, they hope the rest of us might listen -- might realize our actions have consequences for places we'll never see, for people we'll never meet. I also had the pleasure of meeting Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, a young mother and poet who has emerged as one of the country's pre-eminent storytellers. A teacher at the College of the Marshall Islands, the 27-year-old also studies the oral stories that form the fabric of her nation and culture.

Video poem: 'Two degrees is a gamble'

She told me two of her favorites -- and one of her own.

It seems fitting to let her stories serve as the end of mine.

The first is the story of the Ripako, or shark clan, who are Kathy's distant relatives on her mother's side. True to their name, legend has it this group of people could communicate with sharks. They formed a sort of uneasy alliance with the tides, too. Instead of doing rain dances, as would have been common in North America, they held ceremonies on the reef aimed at willing the tide into equilibrium -- and keeping large waves from destroying their homes and flooding them out.

This conversation with the sharks -- and with the water -- helped them thrive in the harsh environment that always has been the Marshall Islands.

Theirs is a story of resourcefulness and survival.

The second story is one of neglect.

It's the legend of a boy who lost his mother, and the evil stepmother who replaced her (evil stepmothers predate Disney, apparently). The stepmother didn't provide the boy with enough food, nor the mat to use as clothing, nor a kite woven from leaves, so he could play. She was cruel and uncaring, not noticing how her decisions pushed the child toward depression and sadness. He had a strong spirit but was unable to provide for himself. The boy suffered in silence, afraid to complain to his stepmother or father, who didn't notice or didn't care, either.

One day, however, the boy was out fishing with his father. When his father dived beneath the waves after a fish, a bird appeared and started talking to the boy.

It was his mother, reincarnated.

Why are you crying, the bird asked her son.

No reason, the boy said.

The bird pecked at the son for lying to her. And when the father re-emerged from the waves, the bird flew away.

This scene repeated itself three times before the boy had the courage to tell the truth: That his stepmother and father weren't feeding him, that he had no mat, no kite. He finally gained the courage to confront his father and stepmother about this, too. When he stood up for himself, his mother, the bird, returned. She appreciated his quiet, respectful resistance to injustice -- so she turned the boy into a bird. The boy-bird flew away from his father and the evil stepmother, forever changed.

The father died in sorrow, searching for his lost son. If only he had noticed the trouble sooner -- had recognized the severity of the situation.

Then maybe he could have saved his son.

And himself.

How to help save the Marshall Islands

From reducing your carbon footprint to urging leaders stop warming short of 2 degrees, there are a number of ways you can help ensure the Marshall Islands will survive for future generations.

Kathy's own story seems influenced by those of her ancestors.

She has emerged as a clarion, moral voice on climate change, shouting into the wind from these distant islands. I first met her at a climate change rally in New York last fall. There, she spoke before the United Nations, reading a poem about how she doesn't want her now-1-year-old daughter, Peinam, who is named after a patch of land on a distant atoll in the Marshall Islands, to grow up without a country.

"They say you, your daughter and your granddaughter, too, will wander rootless with only a passport to call home," she says in the poem, which is written to her daughter. "No one's drowning, baby; no one's moving; no one's losing their homeland; no one's gonna become a climate change refugee." Kathy told me she hoped that speech, and the poem, would wake the world up -- that her story, and the story of her islands, could be the antidote to apathy and the chill of ignorance.

There are small signs the world is listening. The Pope is taking a firm stance on climate. The United States and China have pledged to reduce emissions. Germany is trying to rally the industrialized world to go carbon-neutral. The Guardian and 350.org are trying to make people see investments in fossil fuels as morally shameful.

People who watch international climate negotiations closely, however, say none of it is enough -- not yet -- to keep the world below 2 degrees of warming.

In other words, likely not enough to save the Marshall Islands.

Kathy tries not to get discouraged, but she does.

She keeps answering the same questions from reporters.

Keeps telling her story -- once, then again.

Hoping someone will hear.

Someone will act.

On my last morning in the Marshall Islands, the young mom and I went to a beach in Majuro to film a reading of a poem she wrote for CNN, called "2 degrees."

"There are people -- there are faces all the way out here," she said, waves crashing on a reef behind her, sun tucked behind a cloud. "There is a baby -- walking wobbly, stomping squeaky yellow light up shoes across the edge of the reef."

She paused.

"Not yet underwater."