As a wedding photographer, Tan Mengmeng’s livelihood depends heavily on people getting married, capturing the joy and happiness of a couple’s love.

But China’s marriage rate has been steadily declining and the 28-year-old, who runs a photography studio in central Henan province, has felt the urge to expand her stream of revenue to capitalize off a growing trend: divorce.

In addition to lovers exchanging vows, she now takes photos of couples who want to commemorate, and in many cases celebrate, the end of their marriage.

Official figures show that marriage rates in China are plummeting, declining annually from around 13 million in 2013 to below 7 million in 2022, the lowest since records began in 1985, according to data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

The country saw a slight bump last year, up towards 8 million, but authorities remain concerned about the trend.

Meanwhile, the number of divorces has surged, hitting a record high of 4.7 million in 2019, more than four times higher than two decades ago, according to the data.

The government has tried to reverse the rise, imposing a new law in 2021 requiring couples to go through a 30-day “cooling off” period before splitting. It led to a temporary decline, but the number of divorces has since jumped again, up 25% percent in 2023 from the year prior, data showed.

The two shifts have contributed to a deepening demographic crisis facing the world’s second-biggest economy, exacerbated by a slowing economy, a rapidly aging population and the fact that fewer women are having children after the decades-long one-child policy.

Tan says she pivoted her photography services to divorcees after seeing the long queues outside government offices that handle separation.

Since last year, Tan has photographed some 30 couples, capturing moments of heartbreak and joy as they sever marital ties.

“This is a good business. After all, joy and sorrow are both worth recording,” Tan said.

Changing attitudes towards divorce

Her foray into China’s budding divorce economy reveals a lot about the country’s changing attitude towards marriage.

While divorce used to draw stigma in Chinese society, which has always placed great emphasis on family unity and stability, many young people are now choosing not to get married. For those who do choose to wed, there is greater acceptance if the marriage doesn’t work out.

The cultural shift has spawned a booming business in divorce photography not only for Tan, but also for other photographers hoping to profit.

Photos shared on Chinese social media Xiaohongshu show some couples signing their divorce papers, while others pose with their divorce certificate.

“29 years old. Happy divorce,” one user wrote alongside a photo of her?marriage and divorce certificates side by side.

Companies also now offer services to get rid of a divorcee’s old wedding mementos and any other unwanted mementos in a ceremonial way.

Peng Xiujian, senior research fellow at Victoria University in Australia, says the changing times reflect a younger generation prioritizing personal freedom and career development.

“The idea of staying in an unhappy marriage ‘for the sake of appearances’ or out of obligation is losing its grip,” she said.

Peng, who studies demographic trends in China, also attributed the decline in marriages to both economic and social factors, including the high-pressure work environment, a competitive labor market and the high cost of living.

For those choosing divorce, it’s no longer seen as shameful, Tan says.

“It is not shameful to be brave enough to divorce,” Tan said. “Both parties still have feelings…and want to commemorate the relationship.”

One couple who hired Tan chose a restaurant where they had their first date. The couple ordered a few nostalgic dishes, sitting opposite each other motionless. “At the end of the photo shoot, both of them cried,” Tan said.

While they cared for each other, the wife could no longer stand arguments with her in-laws and her husband was too caught up in work to help resolve the conflicts, Tan said.

Some breakups, of course, are less mutual.

Tan said a man once spent the whole photo session fiddling with his phone. The woman started crying.

When the woman got the photos back, she noticed there weren’t many featuring her ex-husband. “I didn’t dare tell her that it was the man who asked me to try not to take photos of his face,” Tan said.

Soon after, Tan found out the man had booked another photographer to take wedding photos with his new partner.

While female clients account for most requests she receives, Tan says she makes sure men also share the costs.

A divorce factory

In a factory 60 miles outside of the Chinese capital Beijing, Liu Wei and his team run a business that helps divorced couples destroy the evidence of their marriage.

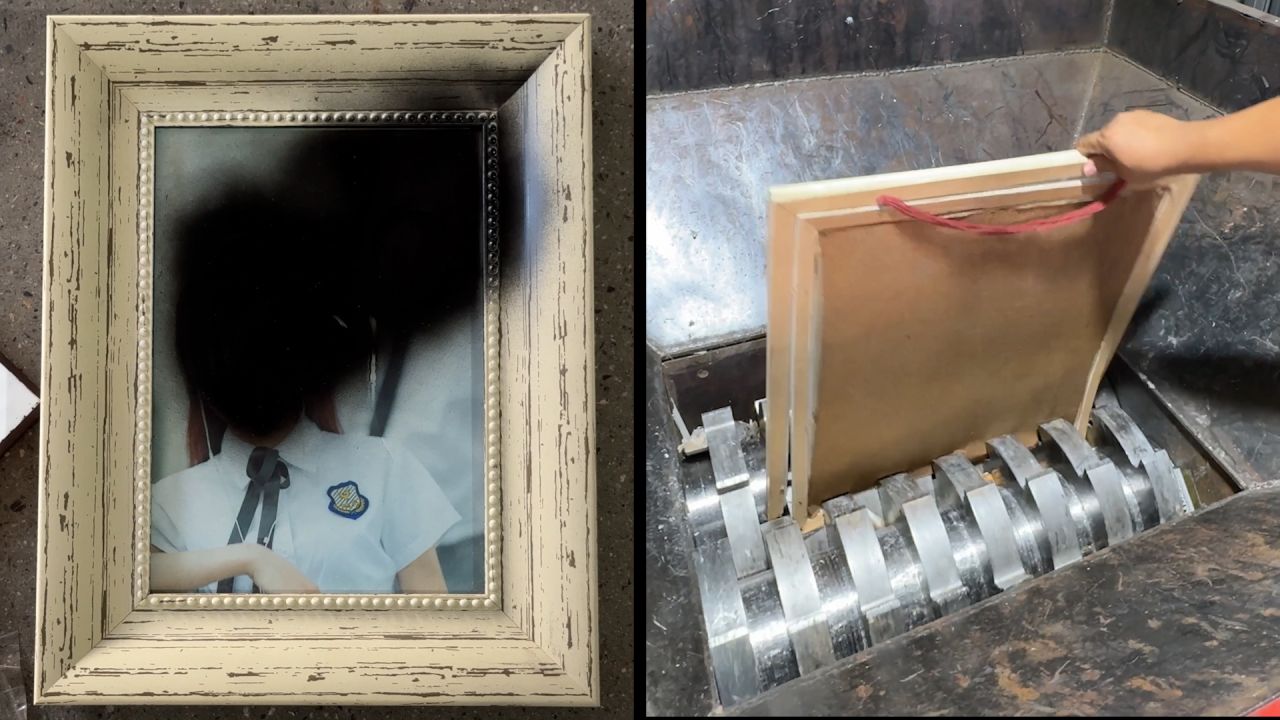

Faces on old wedding photos are spray-painted, to ensure privacy is respected, before being tossed into a crusher along with other tokens of memories.

For those desperately seeking closure and to move on, the entire process is filmed.

Liu said he sometimes feels like a doctor, having to navigate through the separations without getting too emotional.

“A divorce might not necessarily be a bad thing. It could be a good thing. So there’s no need to feel sad about it,” Liu told CNN.

His services, which cost between $8 and $28, have been in such high demand that business is thriving, he said. Since his factory opened in 2021, he’s already destroyed wedding photos for around 2,500 couples.

Gary Ng, an economist with French investment bank Natixis, said that while it is hard to predict the size of the market and room for growth, China’s divorce rates rising means “there is bound to be more economic activities surrounding it.”

Tan, the photographer, is already thinking ahead on how to grow her business. Her latest?plan involves luring return clients in case fate brings the divorced couples back together.

“I’ll give them an 18% discount if the two people remarry and ask me to take photos,” she said.