Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter.?Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

With her mouth wide open, locked for eternity in what appears to be a scream, an ancient Egyptian woman captured the imagination of archaeologists who discovered her mummified remains in 1935 in a tomb near Luxor.

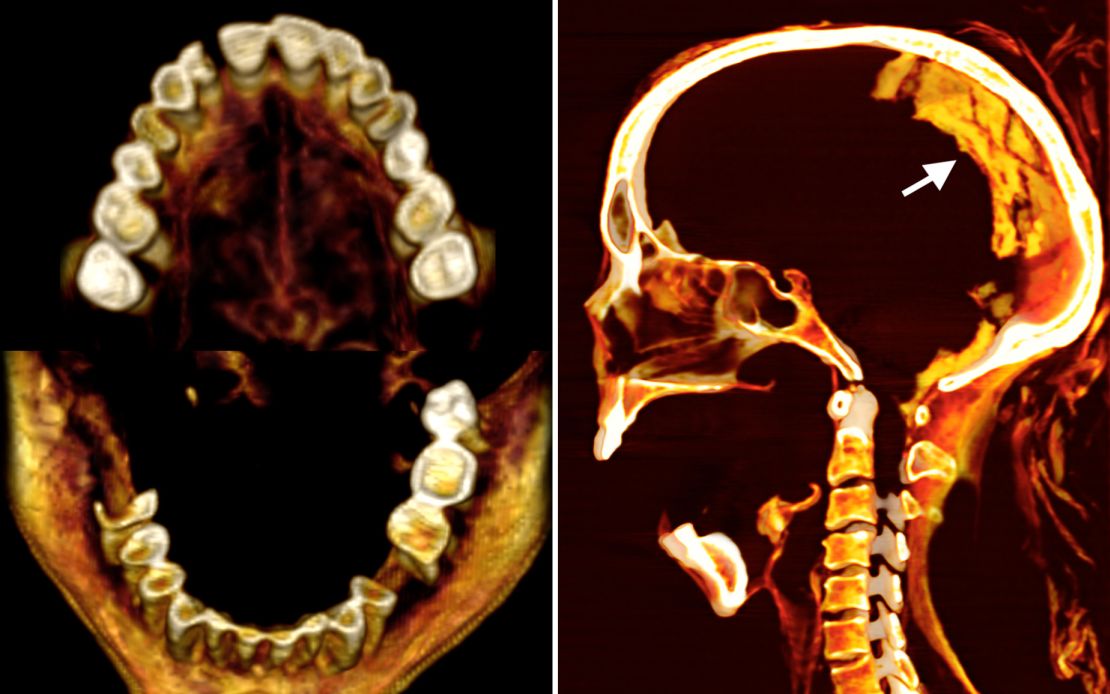

Still fascinated by the “screaming woman” who died some 3,500 years ago, a different team of scientists recently used?CT scans to reveal details about the mummy’s morphology, health conditions and preservation and employed infrared imaging and other advanced techniques to “virtually dissect” the remains and understand what might have caused her striking facial expression.

Their findings, published Friday?in the journal Frontiers in Medicine, revealed that the woman was 48 years old when she died, based on analysis of a pelvis joint that changes with age.?Certain aspects of the process used to mummify her stood out.

Her body was embalmed with frankincense and juniper resin, lavish, expensive substances that would have been traded from afar, said study author Sahar Saleem, a professor of radiology at Kasr Al Ainy Hospital at Cairo University, in a statement.

Saleem also found no incisions on the body, which was consistent with the assessment made during the original discovery that the brain, diaphragm, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys and intestines were still present.

The failure to remove internal organs, the study noted, was unusual because the classic method of mummification from that period included the removal of all such organs except the heart.

The researchers found that the anonymous woman stood 1.54 meters, or a little more than 5 feet, tall and suffered from mild arthritis of the spine, with scans revealing bone spurs on some vertebrae that make up the backbone. Several teeth, likely lost before death, were also missing from the woman’s jaw.

However, the study was not able to determine an exact cause of death.

“Here we show that she was embalmed with costly, imported embalming material,” Saleem said in a news release.

“This, and the mummy’s well-preserved appearance, contradicts the traditional belief that a failure to remove her inner organs implied poor mummification.”

Only a few ancient Egyptian mummies have been found with their mouths open, the study noted, with embalmers typically wrapping the jawbone and the skull to keep the deceased’s mouth shut.

What caused the woman’s chilling expression isn’t clear from the study findings, although the researchers put forward a grisly hypothesis.

What mummification techniques reveal

Saleem said the well-preserved nature of the mummy, the rarity and expense of the embalming material, along with other funerary techniques such as the use of a wig made from a date palm and rings placed on the body, seemed to rule out a careless mummification process in which embalmers neglected to close her mouth.

The mummy’s “screaming facial expression” could be read as a cadaveric spasm, a rare form of muscular stiffening associated with violent deaths, implying that the woman died screaming from agony or pain, according to the study.

It’s possible, the study authors suggested, that she was mummified within 18 to 36 hours of death before her body relaxed or decomposed, thus preserving her open mouth position at death.

However, a mummy’s facial expression does not necessarily indicate how a person was feeling at death, the study noted.

Several other factors, including the decomposition?process, the rate of desiccation, or drying out,?and the compressive force of the wrappings, could all affect a mummy’s facial expression.

“Burial procedures or post-mortem alterations might have contributed to the phenomena of mummies with screaming appearances,” the authors noted in the study.

“The cause or true history or circumstances of the death of this woman are unknown, hence the cause of her screaming facial appearance cannot be established with certainty,” Saleem said via email.

Open-mouthed mummies

The “screaming woman” had been buried beneath the tomb of Senmut, an architect of the temple of Egyptian queen Hatschepsut?(1479–1458 BC) who held important positions during her reign. It’s thought the woman was related to Senmut, according to the study.

The discovery of her remains occurred during an expedition led by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and her coffin is on display there today. Her mummified body is stored at the Cairo Egyptian Museum.

Saleem said she had previously studied two other open-mouthed mummies from ancient Egypt.

One, a mummy thought to be the remains of a prince known as Pentawere, had his throat slit for his role in assassinating his father, Ramesses III (1185-1153 BC). His body was barely embalmed, indicating a lack of care in the mummification process, Saleem said in the news release.

The second mummy was a woman known as Princess Meritamun, who died of a heart attack, and Saleem’s analysis suggested her wide mouth was due to a postmortem contraction?or movement of her jaw.

Randall Thompson, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine, who has studied ancient mummies using CT scans to learn about the origins of cardiovascular disease, called the study helpful and detailed. He said the authors’ preferred explanation for the mummy’s open mouth “made sense.”

“Their investigation helps us to understand what substances were available in ancient times and how our ancestors used them,” said Thompson, who was not involved in the study.

“More broadly, we can learn much about health and disease from the study of ancient mummies,” he added.

“For example, we have learned that heart disease is not new, as many people used to believe. It is literally older than Moses.”