Editor’s Note: This CNN series is, or was, sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over subject matter, reporting and frequency of the articles and videos within the sponsorship,?in compliance with our policy.

On a trip to Florence in 2015, while immersing herself in Italian food and history, Nada Badran had a “eureka moment.” The former management consultant wanted tourists to experience culture and history like this in her home city, Dubai.

The Middle Eastern metropolis — largely built in the past 50 years off the back of the discovery of oil in the Arabian Gulf in the 1960s — is a far cry culturally from the medieval Tuscan city that Badran was inspired by. But she was tired of hearing people say, “Dubai has no soul” or “it could be anywhere in the world,” and felt that this perception was the result of shortcomings in the tourism industry, rather than the city itself.

“I started looking at the local tourism scene, and it wasn’t really anything special, in my opinion: it catered to the mass tourists, people that maybe go on buses, see things to take a few photos, and then go,” says Badran.

And while there’s no denying that the superlative skyscrapers, sprawling maze of malls, and glamorous beach resorts are what attract most tourists to the city, Badran wanted to show them the Dubai beyond that — one with culture, history and traditions, a place with distinctive dishes, people and memories; the Dubai that she grew up in.

So in 2016, Badran set up her own tour company, Wander with Nada, to “show a different side of Dubai” to travelers.

Her bespoke private tours are designed to suit the interests of each visitor, but her favorite itinerary is Dubai’s “old town,” a group of small neighborhoods around Dubai Creek where the city began and Badran spent her childhood.

“I think it has a very unique personality,” she says.

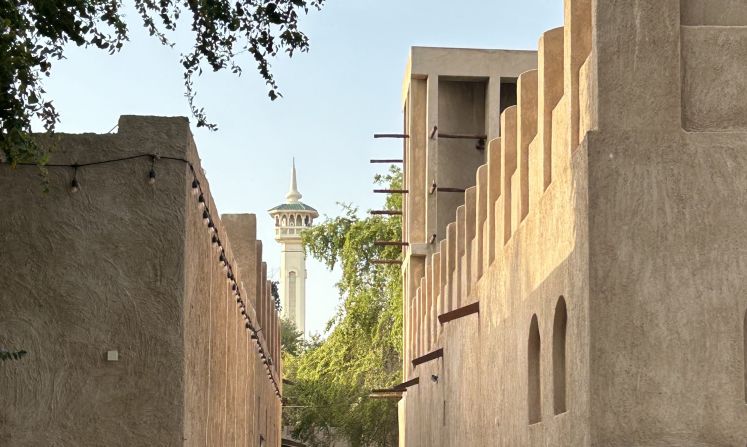

A historic neighborhood

History is often equated with “soul.” Cities that wear their past lives on their sleeves, like Rome, Athens, or Edinburgh, have a certain character or gravitas: the architectural equivalent of wrinkle lines and graying hair.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a relatively new country, formed in 1971. Yet Dubai, one of its seven emirates and most populous city, has a much longer history: strategically located on the tip of the Arabian Peninsula, Dubai has been a trading port for centuries, particularly between Oman and today’s Iraq.

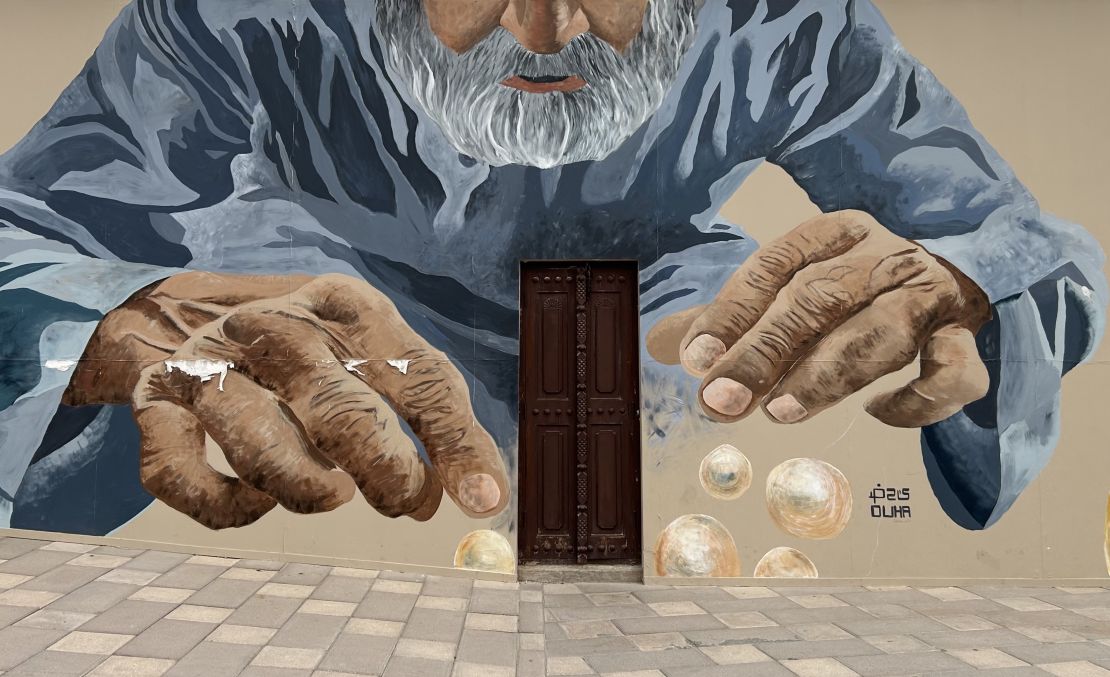

People made their livelihood through pearl farming, and the settlement was little more than a fishing village before the Al Maktoum family, descendants of a semi-nomadic Bedouin tribe called the Bani Yas, settled there in 1833.

This is where Badran starts our tour (which took place just before Dubai experienced historic flooding) — in Al Shindagha, the neighborhood where the city’s first homes were built around 200 years ago.

While there’s little left to show for the pearl diving trade that put Dubai on the map, Badran feels it is important context to understand the city — including the acknowledgment of some of its more controversial history, including exhausting and brutal working conditions for divers.

Plastered in coral and gypsum, the burrow-like homes have small windows to keep the heat out, with a myriad of small rooms around a central courtyard, designed to host multiple generations of a family under one roof. The Al Maktoum family home is still there, where the city’s current ruler, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, was born in 1949.

Today, no one lives in the neighborhood. Instead, these homes are museums, each paying tribute to a different aspect of Emirati heritage, like “Al Talli,” a traditional embroidery skill that was recognized as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO in 2022; or the complicated manufacturing of Arabic perfume scents and the role of fragrance in Emirati hospitality. There’s a house dedicated to fishing, and another to the multitude of uses for palm trees, where craftspeople turn rough palm brush into rope in front of your eyes.

From house to house, Badran weaves historical tales, painting a picture of what life was like for early settlers in the city, and carefully explaining how each element relates to life in the historic Dubai Creek.

“If you ask me what my profession is, I don’t say tour guide — I’m a storyteller,” says Badran.

A temporary population

An oft-cited fact about Dubai, and the UAE in general, is that it’s a diverse melting pot of 200 nationalities. But it’s not just in the present day that it hosts a culturally varied population: even the original pearl fishing communities were a mix of Arabs, Persians, Sudanese, and Balochis, an ethnic group from South and West Asia.

“Dubai has a very fluid population — people come and go, come and go,” Badran says. The influence of other cultures is woven into the fabric of the city, and Badran points this out at the souks, across the creek from Al Shindagha: Indian agarwood used to create oud for perfume, Persian saffron, and rich Medjool dates from Saudi Arabia.

In the historical Al Fahidi district, we wander through a maze of alleys, between the former homes of Iranian traders who settled there in the 1890s. A little over 10% of the original dwellings remain there and like Al Shindagha, no one lives there: it was revitalized in the 1990s to host shops, cafes, and boutique hotels. While beautiful, it feels oddly empty — soulless, some might say. “It’s an area that’s frequented by people, but they’re mostly tourists,” says Badran, adding, “Try telling Dubai residents to come here — you’ll have to pay them.”

And that’s a problem. Heritage is not just historic buildings, but the communities that build them. As architecture professor Djamel Boussaa put it in his 2014 paper on Dubai’s urban heritage, it’s the inhabitants of a city that “bring life to the built environment” and so social communities need to be conserved alongside heritage sites.

“Urban conservation does not necessarily mean preserving a building but reviving its spirit and life,” Boussaa writes. “It means being flexible enough to adapt the objectives of rehabilitation to the needs of modern living while respecting the local community values.”

Today, the city’s largely migrant population, accounting for 92% of residents, is temporary; there to work without putting down roots, as there are no long-term permanent residency options. Dubai’s transient population, from the deep past to the present day, leaves very little room for community culture to settle, or grow.

A changing city

Badran, despite feeling deeply rooted in the city she has called home for the best part of three decades, has experienced this too. She saw a high turnover of school friends, most of whom she hasn’t seen since they were children, and her own family, who moved to Dubai from Jordan in the 1980s, will ultimately leave the city.

But as a frequent traveler herself, she also knows that people make a place, and has endeavored to make the people who live in the city “an integral part” of her tour.

At the museum, Badran facilitates conversations with craftspeople who have inherited their perfume-making or fabric-stitching trade from their parents, and wandering through the Deira souks, she hands over her storytelling platform to Rashid Haghaght, an Iranian spice trader who has taken over his father’s store. (He talks me through how to spot real and fake saffron in the market —?a useful skill for the world’s most expensive spice.)

“The most important part (of the tour) is the conversations and interactions with the community,” Badran adds. “I want (visitors) to actually have a conversation with someone who’s from here, who can tell them something they didn’t know before.”

While Old Dubai is one of Badran’s most popular tours, she also creates itineraries for other districts, as well as neighboring emirates Abu Dhabi and Sharjah. For visitors who really want to get off the beaten track, Badran recommends exploring Al Rigga in Deira, an area adjacent to the souks that’s home to an eclectic mix of stores and Naif Souk, a clothing market; and Al Karama, a neighborhood filled with South Asian restaurants and fabric stores.

Knowing the city “inside-out,” Badran creates itineraries that are a careful curation of places she’s frequented over her years living in the city. “Time has not affected some corners, and those are the parts that I love to go to,” she adds.

Of course, though, things change.

Badran leads me through the narrow alleys around the Dubai Old Souk, home to stores run by Indian-origin families. You won’t find the clutter of tourist souvenirs here — instead, brightly colored floral garlands, Hindu god figurines and prayer beads adorn the doorways.

But many of the stores are closed or boarded up. One of the city’s two Hindu temples, located a stone’s throw from these alleyways, was closed in January and relocated 35 kilometers (22 miles) away, near Jebel Ali, Badran explains. Many businesses are moving with it, fragmenting a community that has been here since the two temples opened in 1958.

When I ask her how she feels about the way the city constantly changes, Badran describes it as “humbling.”

“I always say, in one year, if you come back, you will find it to be a different place,” she adds.

It’s hard not to see things like the temple relocation as a loss of culture. But spending time in Dubai’s old town, drifting between century-old homes built by once-nomadic people, and souks run by migrant merchants, tasting spices from Iran, touching textiles from India, sipping tea from China and scents from Oman, the restless churn becomes the common thread connecting disparate peoples, products, places.

“Dubai is about opening your mind,” Badran says, “and embracing this diversity that makes it unique.”