Once a year on the first Monday of May, the carpeted steps of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (“the Met”) become home to the most scrutinized costume party of the year. The dress code to end all dress codes, over the years the Met Gala theme has explored lofty subjects such as East to West international relations (“China: Through the Looking Glass,” 2015), the visual history of catholicism (“Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” 2018) or even the value of art in the age of mechanical reproduction (“Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology,” 2016). This year, Andrew Bolton, lead curator of the Met’s fashion museum, The Costume Institute, has instructed celebrity guests to unpick the words of one of the most famous science fiction writers: JG Ballard.

In February, the Met revealed Ballard’s 1962 short story “The Garden of Time” as the forthcoming red carpet theme. It will accompany the main exhibition, titled “Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion,” featuring pieces from the Costume Institute archive that span four centuries. Many of the garments are so delicate, they can no longer be touched — let alone worn — without proper conservation equipment. Bolton describes it as “an ode to nature and the emotional poetics of fashion.”

In the “Garden of Time,” Count Axel and his wife live in a grand Palladian villa with a sprawling walled estate. A crystalline meadow of glass-like “time flowers” spring out across the plot, while over the horizon, far in the distance a whip-yielding angry mob inch closer and closer to the Count’s villa. Everyday Axel picks the head of a time flower, winding back the hours and reversing the mob’s advancement over the hill until all the blooms are finished — an inevitability that looms large over the story’s few pages. Finally, the crowd storms the wall, only to find a dilapidated villa and two stone statues in the image of the Count and Countess. Perhaps his most ambiguous story, the story’s themes of decay, ruin, beauty and fragility are in direct conversation with the theme of “Sleeping Beauties.”

There is little glitz and glamor in Ballard’s world — or if there is, it doesn’t last for long. Since the 1950s, the late British author — who died in 2009 — has built an oeuvre centered almost exclusively on dystopian catastrophe, unbridled violence and the dissolution of the bourgeois psyche. Whether the scene is a luxury high-rise apartment complex or an affluent gated community in the south of France, Ballard’s thesis remains the same: The glittering sheen of upper-middle class life is nothing but a thin veneer, seconds away from cracking.

Even if you don’t recognize his name, you are likely to have come across Ballard’s unnerving musings on human psychology. For example, if you’ve watched Steven Spielberg’s 1987 film “Empire of the Sun,” based on Ballard’s 1984 novel fictionalizing his own experience as a child in a Chinese internment camp during World War II. Or David Cronenberg’s 1996 adaptation of the writer’s 1974 novel “Crash” — following a group of people sexually aroused by auto collisions — which was met with boos and early exits when it debuted at Cannes Film Festival. But it’s not just film that has been directly inspired by Ballard. His worldview has infiltrated art, music, architecture and fashion, perhaps more consistently than any other 20th-century author.

Fashion designers in particular have long been compelled by the Ballardian vision. In 2021, American designer Thom Browne’s Spring-Summer catwalk at New York Fashion Week also imagined life behind Count Axel’s garden wall. Browne conjures the story’s final image of the stone aristocrats through silk-screened T-shirt dresses printed with Greek and Roman statuary, as well as wide brushstrokes of clay that cracked across the model’s face. Israeli designer Alon Livné created a collection in 2013 prompted by the 1966 novel “The Crystal World;” while in 1998, London-based designer Andrew Groves launched a Spring-Summer collection based on the 1997 story of a bored, moneyed and murderous enclave in Estrella de Mar called “Cocaine Nights.”

“There’s something about Ballard that takes the normal or the every day and makes it horrific and subversive,” Groves, who first borrowed the book off of a friend more than 27 years ago, told CNN over Zoom. “He was really good at identifying the dystopian elements of the 20th century. And designers in the ‘90s like myself, McQueen, we were using fashion as a lens to think about its role in society and what it means.”

But none of Ballard’s stories have been so habitually reimagined on the runway as “Crash.” The novel’s (and later the film’s) thorny images of crunched metalwork, black eyes and fishnets have become a key reference point for designers, from fledgling college graduates to brands on the fashion week circuit. Designer and former Moschino creative director Jeremy Scott crafted his first ever catwalk at Paris Fashion Week in 1997 on these visual cues, going as far to send French TV journalist Marie-Christiane Marek an actual car door as part of the invite.

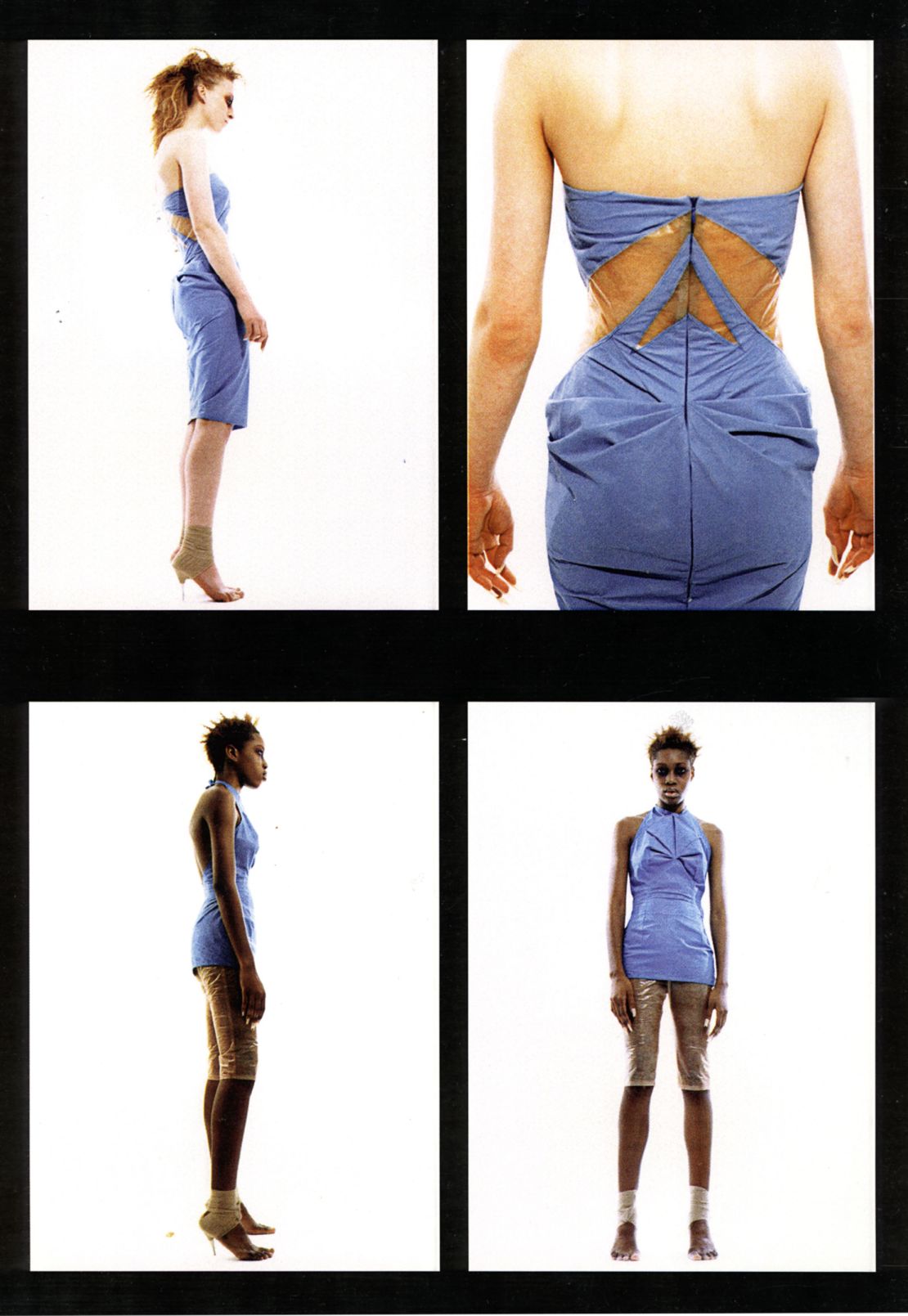

“I remember being so completely stunned at the scenes where they were getting excited over these car accidents, and the cars and smoke and the mangled bodies and car parts,” Scott said over video call. The collection, titled “Body Modification,” featured hospital gowns tucked and pleated like couture frocks, and nude-colored plexiglass inserts with stiletto heels bandaged to models’ feet. “The hospital gowns were made of paper,” said Scott. “The whole point was its ephemerality. And now with the Met Gala theme, the beautiful flower that dies as soon as it’s plucked, it connects back to fashion being ephemeral. It’s a fleeting moment, even if we hold onto it for a lifetime.”

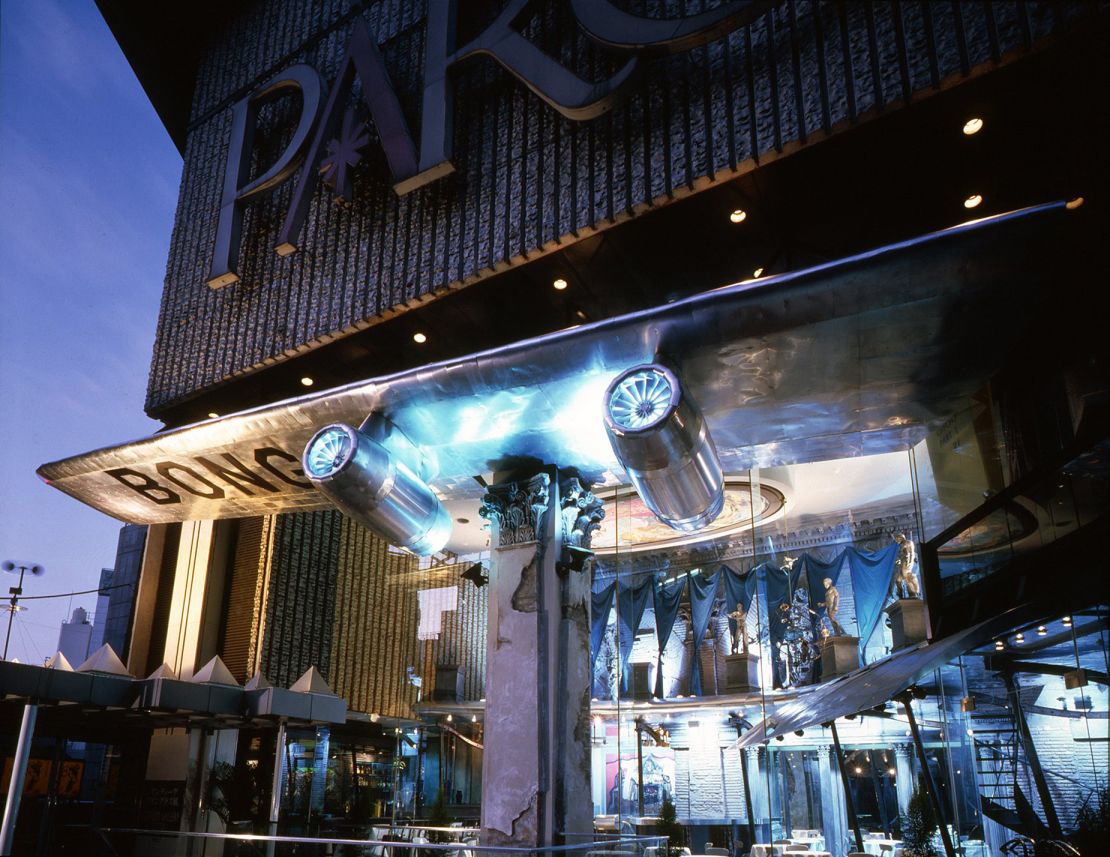

The influence of “Crash” in particular has spread like an oil spill across the arts. In 1986, British architect Nigel Coates built Caffè Bongo in Tokyo — a restaurant whose frontage features a lifesize aircraft wing crashed into a Roman column. “I’m more interested in the culture of architecture and how that can be contributed to in a variety of ways, rather than the proof of architecture through building,” said Coates in a 2011 lecture on Ballardian architecture. “I find a cohesive connection with the story “Crash,” and the way in which the perversity of sexual pleasure combined with danger and pain has a certain combination which can find its way in architecture.” Criticism of Caffè Bongo briefly brandished Coates as a dangerous architect, after many believed it was unbuildable. “I proved them wrong,” he said.

From Madonna and Charli XCX to Radiohead and Joy Division, musicians across genres have dedicated records, album artwork and track titles to Ballard. Madonna’s 1998 song “Drowned World/ Substitute for Love” takes its name from the 1962 novel, while Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis pinched the short story title “Atrocity Exhibition” before reportedly ever having read Ballard. The album artwork for “Crash” (2022) by Charli XCX mingles the gore of a car wreck with sexual overtones, as she straddles a totaled car bonnet in a black bikini — staring into a smashed windscreen with a trickle of blood seeping from her temple. The Manic Street Preachers sampled the infamous Ballard quote “I wanted to rub the human face in its own vomit, and force it to look in the mirror,” in their 1994 track “Mausoleum.” Even Radiohead’s resident artist Stanley Donwood, who has created every album cover for the band since 1994, was commissioned by Fourth Estate Books in 2015 to redesign the look of Ballard’s 21 novels.

But what will we see out on the Met steps? While the style press predicts a torrent of peony-printed gowns, a quick scan of Ballard’s words will hopefully steer celebrities in a darker direction. “There’s something I think within fashion about things being slightly off,” said Groves.?“That’s what makes (clothes) interesting.”