Editor’s Note: The CNN Original Series “Space Shuttle Columbia: The Final Flight” uncovers the events that ultimately led to disaster. The four-part documentary concludes at 9 p.m. ET/PT Sunday.

When NASA’s Columbia shuttle launched on January 16, 2003, it carried a crew of seven astronauts who had spent nearly three years getting to know one another before venturing on a 16-day science mission into space.

NASA selected astronauts Michael P. Anderson, David M. Brown, Kalpana Chawla, Laurel B. Clark, Rick D. Husband and William C. “Willie” McCool, as well as Ilan Ramon of the Israeli Space Agency for the mission in July 2000.

During the day, the crew trained together, working on the camaraderie that would help them as a team. After work, the crew members and their families would gather for cookouts and laser tag at one another’s homes.

In pictures: Space Shuttle Columbia's final flight

The STS-107 mission crew included five men and two women of diverse backgrounds, religions, interests and hobbies. But rather than let the differences divide them, the trainees came together and encouraged one another, said Laura Husband, daughter of STS-107 Commander Rick Husband.

“I grew up with seeing this beautiful picture of all these different perspectives, and they loved each other and worked so well together,” Laura told CNN. “They celebrated each other.”

Before the launch, the crew went on an outdoor team-building trip in Wyoming. As the shuttle commander, Rick thought it would help the team bond.

“I watched my dad really build a team, and he did that with our family, too,” Laura said. “He was a good leader and a good team player.”

Crew member Brown filmed the journey. Before becoming a medical doctor and astronaut, he was a collegiate varsity gymnast who performed as an acrobat, 7-foot unicyclist and stilt walker.

The footage Brown captured shows crew members laughing and joking with one another, making fun of campfire brownies that looked like bear scat and anticipating their mission with an infectious hopefulness.

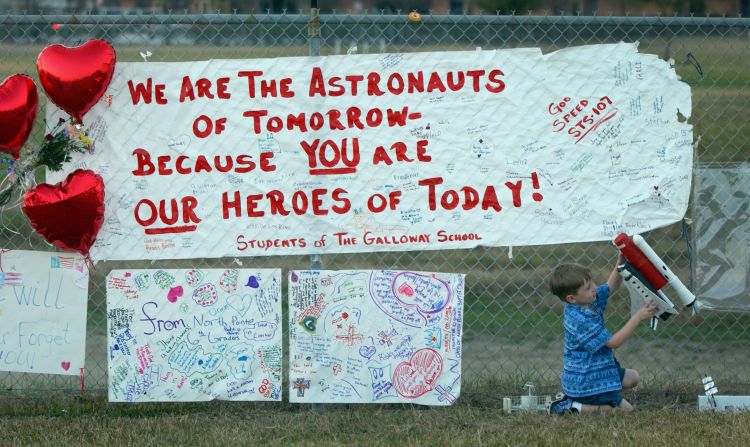

“When they came back, it was like their bond was forever,” said Rosalind Hobgood, NASA secretary for the crew, in the CNN docuseries. “They walked in sync with each other. It was like left, right, left, right. They were the Columbia crew. They were STS-107. They were a unit.”

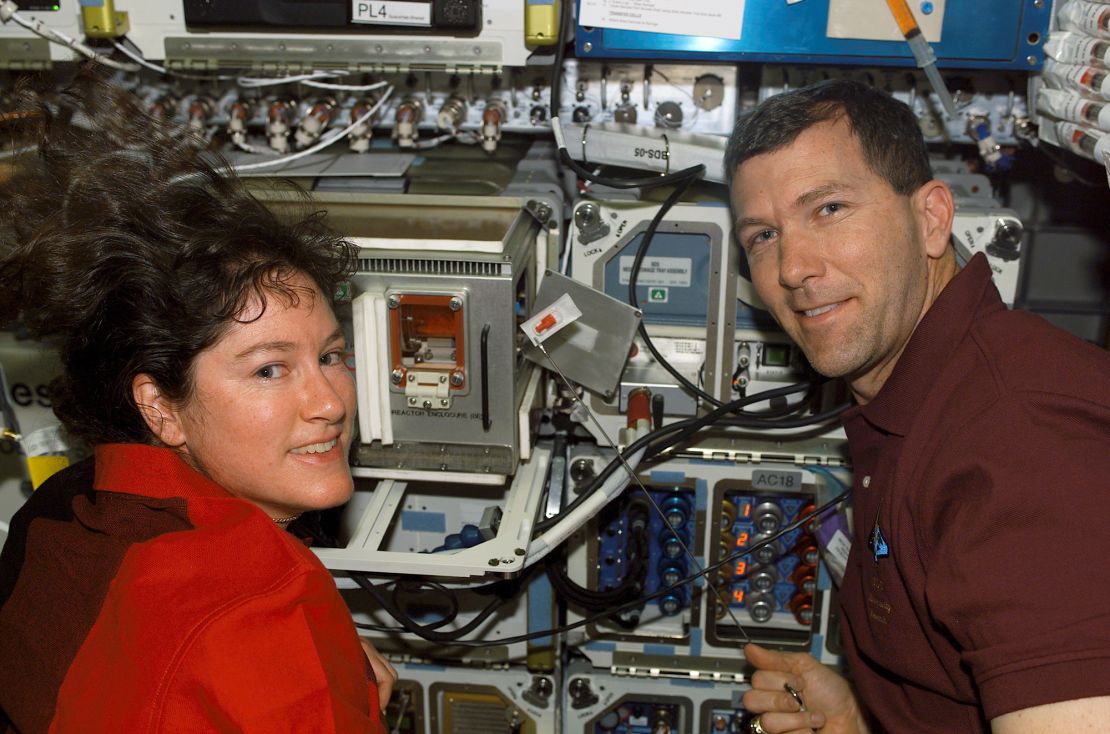

After launching to space, the crew split into two teams to conduct dozens of round-the-clock experiments and gather valuable science data while taking time to exchange emails and enjoy a couple of video calls with their families.

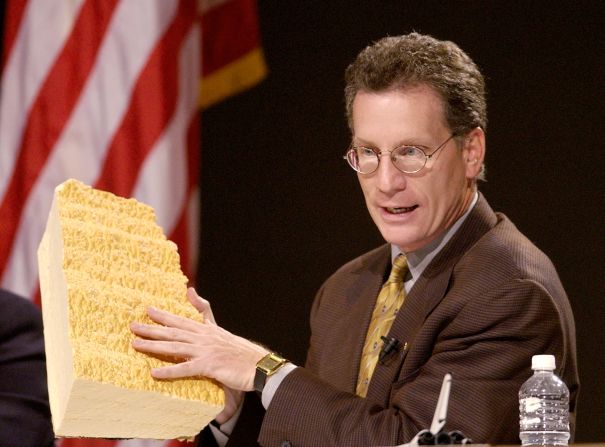

When Columbia reentered Earth’s atmosphere on February 1, 2003, the shuttle broke apart over Texas as a result of damage from a foam strike on the shuttle’s left wing after liftoff, and the crew was tragically lost.

Now, more than two decades after the loss of the Columbia astronauts, their family members continue to honor the memories and legacies of their loved ones.

Making spaceflight safer

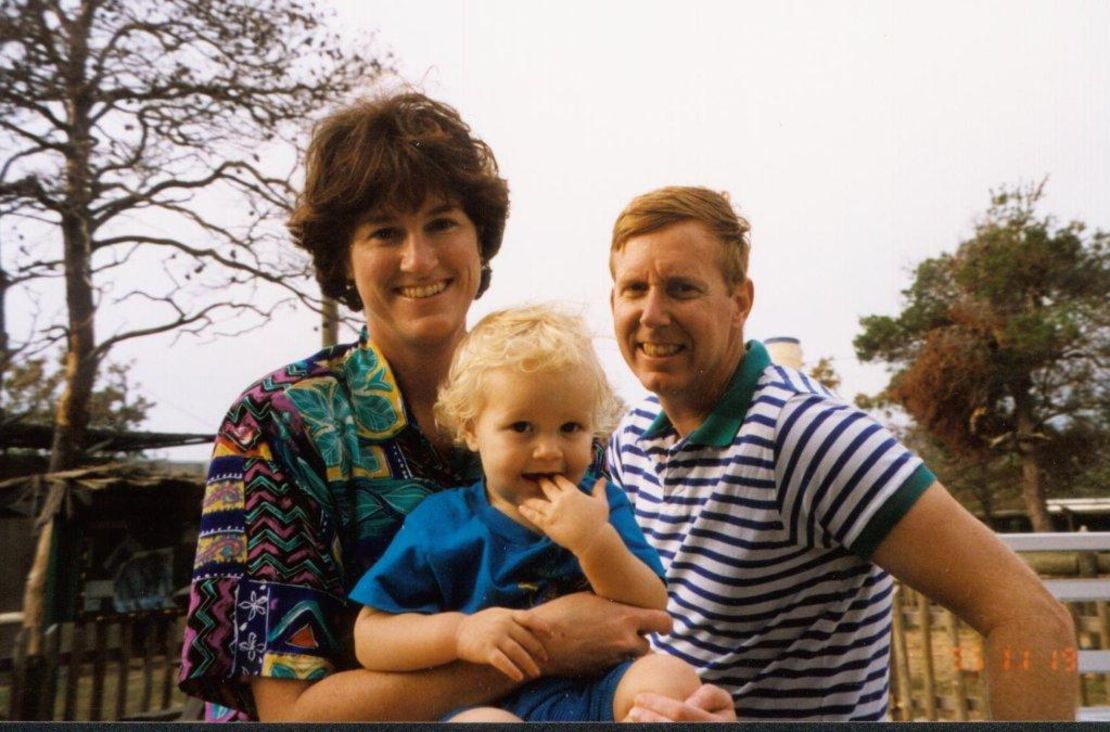

Jonathan Clark first met his future wife, Laurel, at a US Navy diving course for medical officers at the Naval Diving and Salvage Training Center in Panama City, Florida, in February 1989. But he joked it wasn’t like the iconic bar scene from the 1986 movie “Top Gun.”

Jonathan and Laurel each teamed up with a diving buddy, and the two pairs were next to each other during training. She had a tenacious spirit and was a natural in the water, outswimming all the men in the course “like a race boat,” he said. She was incredibly calm under pressure, even when her diving helmet system flooded and she nearly died.

After completing the course, the two went on dive trips together and formed a friendship that bloomed into a deeper relationship built on mutual respect and admiration, Jonathan said.

Laurel became one of the first female submarine medical officers and aced numerous achievements before becoming an astronaut. She was an outdoorsy person and avid sailor who loved camping and nature. And she was always smiling.

“She was just a fun, cheerful, positive role model,” he said. “And quite honestly, I absorbed a lot of who she was because I realized that’s a better way for me, not just being that kind of machismo, cocky guy, but to think about things and care about other people. She was very emotionally intelligent and had a wonderful ability to read people and be able to make any situation better.”

Laurel also enjoyed being a mother and excelled at it, Jonathan said.

“She made everything joyful all the time,” said her son, Iain Clark, in the series. “She was my whole world. I relied on my mom for so much.”

The wisdom and insight that Jonathan gained from Laurel helped him process his grief after losing her, he said. She taught him to accept reality but never abandon hope, and that humans grow and learn from loss and hardship.

“What I’m doing now is working to make human spaceflight safer by focusing on what lessons we can learn after catastrophic events,” Jonathan said. “It’s not about finding who’s at fault. It’s about finding the cause and addressing and dealing with that.”

Jonathan Clark was a flight surgeon in mission control at Johnson Space Center in Houston during the final Columbia mission. After the tragedy, he turned his efforts to the recovery and investigation that followed. He became a member of the crew survival working group to determine the implications and lessons of what might have enabled the crew to survive, and how those lessons could be applied in the future.

“I kind of look at the legacy of Columbia as not just the science that they recovered from the mission, but also the crew survival enhancements learned,” he said. “Spaceflight is so much safer now than it used to be.”

Since leaving NASA in 2005, Jonathan has worked with companies regarding crew safety for space missions and other high-stakes operations. And he has discovered the “best job he never knew existed”: becoming a grandfather.

Iain Clark now has a daughter named Laurel, and she has many of her namesake’s attributes, including a love of nature, water and the outdoors, “with a bubbly personality like you wouldn’t believe,” Jonathan said.

“God gave Laurel back in a small way,” he said.

A journey of faith

Rick Husband and his future wife, Evelyn, grew up a mile down the road from one another in Amarillo, Texas.

They went to the same high school, but they didn’t begin dating until after running into each another in college during a basketball game at Texas Tech University. Their first date was on January 28, 1977, and right away, Rick knocked over a glass of water and bumped his head on a light trying to clean up the mess.

Soon after, he told Evelyn he wanted to be a Dallas Cowboys football player or an astronaut, but he didn’t think being a football player was realistic, which made her laugh. Rick had worked toward the goal of becoming an astronaut since he was 4 years old.

The two married after college, focusing on growing their faith together.

Rick was incredibly humble, Evelyn said. When people asked about his job, he simply said he worked for NASA, and only would admit to being an astronaut after further questioning, she said. For Rick, faith came first, family second and his job was third, Evelyn said.

No matter how demanding his job was, Rick always made time to spend with his family, his daughter Laura said. He decorated her ceiling with glow-in-the-dark stars, acted out skits with her at church and took her on father-daughter camping trips, creating sweet memories that she still cherishes. She loved how goofy he was and liked to hear him sing because it was one of his favorite things to do.

Faith helped Evelyn and Rick navigate rough patches in their marriage, she said. When Rick entered a quarantine to prevent crew members from getting sick before launch, he told Evelyn, “I feel like we’re in the best place we’ve ever been in our marriage,” she recalled. And she told him she felt the same way.

From space, Rick and his family shared a video call on January 28, 2003, and Rick wished Evelyn a “happy dating anniversary.” It was the last time they ever spoke.

Evelyn and Laura relied on their faith to navigate their grief after the disaster, and they felt like God protected them through some of the worst days, they said.

Eight months after her loss, Evelyn read the accident investigation report that was released. She remembers struggling with her anger, realizing that NASA knew the foam strike may have caused an issue and that maybe something could have been done to save the crew. She prayed that she wouldn’t be bitter.

Evelyn has since attended seminars hosted by NASA to remember the Columbia tragedy and share lessons learned, so that history never repeats itself again.

“I have a ton of friends at NASA, and I still do,” Evelyn said. “Nobody did this on purpose. NASA had to do a really hard look after (the) Challenger (explosion in 1986), and then they needed to do a really hard look after Columbia. So it was super important to me to not be bitter and to maintain this relationship with them, and it’s really paid off.”

Within the past 10 years, Evelyn has become the only female board member of a ministry called Fathers in the Field, a program that pairs mentor fathers with fatherless boys for a three-year commitment. She wishes that her son, Matthew, could have had that experience after losing his father.

Laura was 12 when her dad died, forcing her to grow up quickly. Now, she reflects on how intentional her dad was with his time. Faith and her love of storytelling, singing, dancing and acting have helped her along the way, she said.

“My desire is to live and foster beauty in the world and intentionally do something together with other people to bring hope in some way,” Laura said.

Growing up with the other crew kids, Laura remembers the adults talking over barbecue while the youngsters went upstairs and played for hours.

Laura and Tal Ramon, son of Ilan Ramon, were only about a year apart in age, and they would paint or play piano together. Now, Tal is a singer-songwriter, pianist and composer. And many of the Columbia kids are creative in a variety of ways — something that connects them beyond tragedy.

“It is something that existed in all of us, and maybe it’s because we watched our parents do big things,” Laura said. “That gave us stability and security to dream big.”