Spread across sprawling convention centers, art fairs often deal at a grand scale: huge floorplans, major artworks sold for millions, dramatic installations and, sometimes, big stunts.

But in Chicago, one fair brings the art down to a miniature size, with its participants making?itty-bitty paintings, sculptures and other works to be displayed at 1:12 scale in dollhouse-sized booths. Barely Fair, now entering its fourth year, brings together both well-established commercial galleries and artist-run project spaces, and has previously featured a “mini bean” by Anish Kapoor and other little works by the likes of Barbara Kruger, Yoko Ono and Rebecca Morris. The fair runs the week of Expo, Chicago’s (regular-sized) annual international fair and opens on April 12 at Color Club.

The idea for Barely Fair originally began as a joke tossed around between the directors of the artist-run space Julius Caesar, but they quickly realized its potential as a legitimate calendar event in the art world.

“We thought it would be a really brilliant idea if we if we did it as well as possible — kind of like how a good joke is best told straight,” said Roland Miller, a co-founder of Barely Fair. He added: “There’s a lot of complexities that have gone into this silly joke that we came up with.”

After a successful first year in 2019, Barely Fair paused for two years as the Covid-19 pandemic brought art fairs to a halt (and, later, an uneven return). In 2022, the founders, who include the artists Josh Dihle and Tony Lewis and the curator Kate Sierzputowski, decided to start up again.

“We weren’t sure if anyone was going to remember it or not,” Miller recalled. “On that first night in 2022, the line to get into the fair was an hour long.”

Small but mighty

Barely Fair may offer miniature art, but it’s a full-sized event in every other regard, this year bringing together 36 galleries, that often showcase multiple artists per booth. Artists and their galleries are responsible for producing all of the small works, but Barely Fair’s team helps with installation as needed.

Ellie Rines, founder of the New York City gallery 56 Henry, has exhibited with Barely Fair for the past two years — this year with the work of the Los Angeles-based artist Daid Puppypaws, who is showing readymade sculptures of road reflectors collected over a 15-year-period. Rines finds the small booths tend to draw more attention than the hustle-and-bustle nature of larger fairs.

“The challenge with presenting work at an art fair is that you feel like people won’t look closely enough at it — they’ll give it a cursory glance,” she said in a phone call. “And actually, by minimizing the scale, it creates an environment where you’re challenged to look more closely.”

“At its best, an art fair is a way to get a bunch of art consolidated into one venue… and download it into peoples’ psyches as expediently as possible,” she added. “And I think that Barely Fair is much more successful at that.”

For nascent galleries and artists, Barely Fair is a more accessible way to participate in Chicago’s art week, which draws curators and collectors from around the world. For international spaces, it’s a footprint in the US outside of coastal art hubs. But for many participants, including art world mainstays who have been on the circuit for years, as Miller pointed out, it’s just fun.

“Other than the parameters of the booth, it’s pretty freeing,” said Julia Fischbach, who co-owns the Chicago-based gallery, Patron. Exhibiting this year for the first time with a solo presentation by Alice Tippit, the Patron booth features postcard-sized drawings of sinuous snakes alongside found feathers cradled in custom wood boxes. Without the “heavy expectations” of other art fairs, Fischbach added, “it’s more playful.”

Room for interpretation

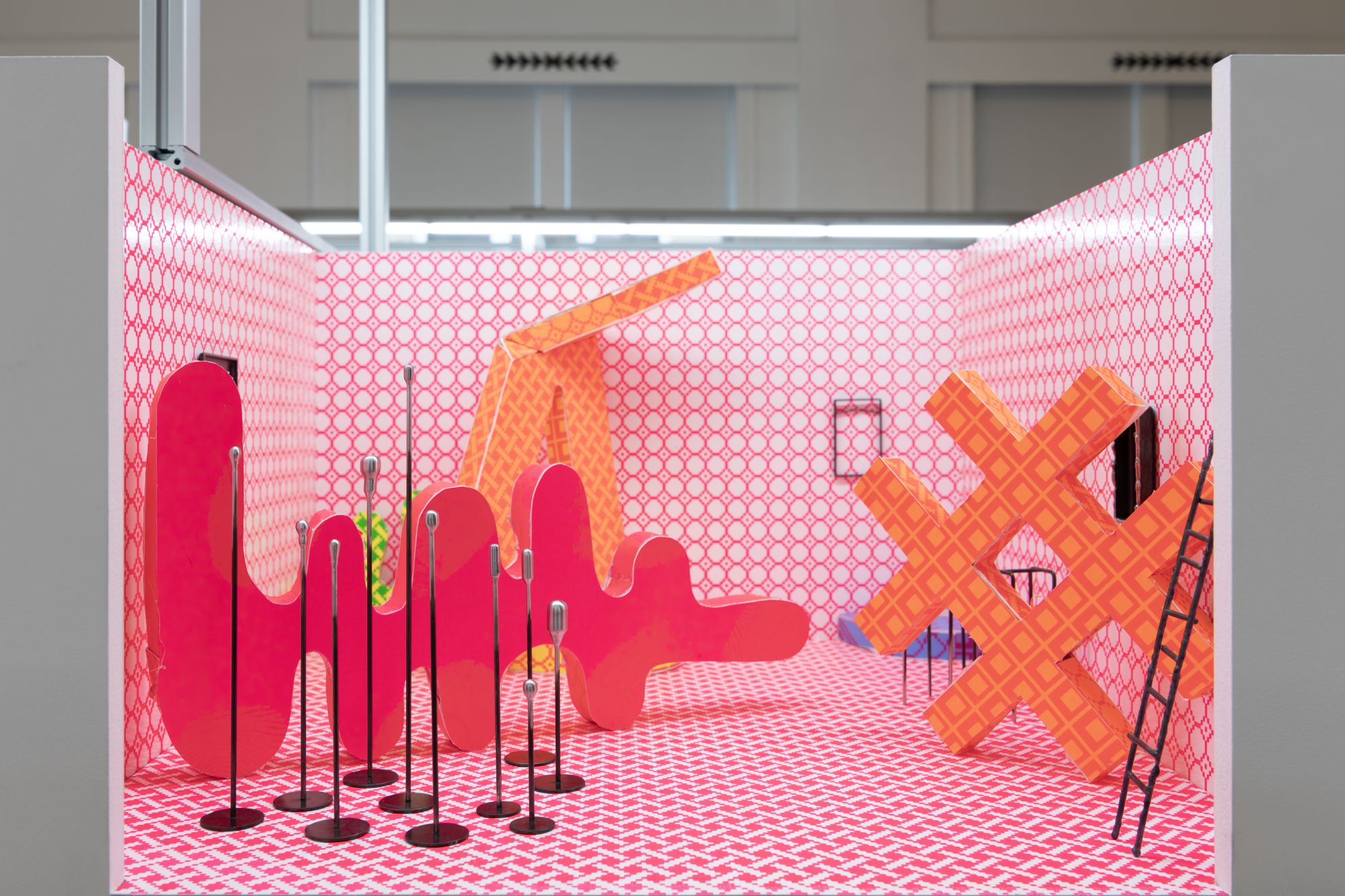

Artists and gallerists have approached their booth’s parameters in different ways, with some spaces set up with a more traditional feel of a gallery’s floor sculptures and wall paintings, laid out how a thumb-sized visitor might engage with the space. Others have transformed their booths into busy rooms, adding wood wall panels, carpet and furniture to complement the art. Last year, Rines of 56 Henry, opted for a single felt sculpture by Al Freeman mounted on a wall — one of her “soft hard penises,” Rines described.

“I think it took about one to five minutes,” she said of the installation. “There might have been some Velcro involved or something.”

The Chicago-born, Los Angeles-based artist Amanda Ross-Ho, exhibiting with the Portland gallery ILY2, is using her booth at this year’s fair to look back at one of her formative artworks and bring it full circle. In 1998, Ross-Ho began playing with monumental proportions in her art, creating a 7-foot-tall t-shirt that read “LEAVE ME ALONE” in a bold sans-serif font, a nod to the declarative slogan tees of fashion designer Katharine Hamnett.?Ross-Ho has created various iterations and sizes of the shirt over the years; now, her smallest version, “LEAVE ME ALONE (XXXXXS), 2024,” measuring only a few inches, will come home to Chicago — where she first ideated the work.

“(It’s) inverting the dynamics of making a monument at small scale,” she said, explaining that Barely Fair “happened to feel almost tailor-made” for her work.

Chicago, she added, has “such a long legacy of artist-run spaces, and truly alternative models to the art market and the art fair system… so there’s something about the miniature art fair that’s so Chicago, and I love that.”

Ross-Ho is selling eight wearable “LEAVE ME ALONE” shirts at Barely Fair for the occasion, but sales are not the draw, she emphasized. Price points for artworks at Barely Fair typically range from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, with some of the works not meant for sale at all.

Still, that’s not to say collectors aren’t eager for the works on display. Last year, the Belgian gallerist Tatjana Pieters sold out her booth, which featured 3D-printed pet fish sarcophagi (containing real fish bones) by Charles Degeyter and Renaissance-inspired mini canvasses by Mae Alphonse Dessauvage. Pieters called it an excellent “trial run” for Degeyter’s work, and showed him again at NADA Miami during Miami Art Week, selling out the booth once again — this time, with larger works.

“The challenge is to get the viewer into the world of the artist on such a small scale, and last year that worked,” Pieters said in a phone call. “Now I’m curious to see if it will work? again this year.”

As Barely Fair continues to gain a reputation, its founders have discussed what it might look like to bring the event to other cities and expand its small footprint. However they might ‘grow,’ though, Miller says they want to stay true to the exuberant spirit of the fair.

“I’ve never been a part of anything where people had just such strong emotions of joy — it’s not like a normal reaction in the art world; it’s rare,” he said. “And when you feel it, you really want to hold onto that.”