“My God, it’s dull,” said interior designer Steven Thomas of the British retail landscape in 2024. As the creative force behind the look of the wildly popular 1970s London fashion store Big Biba, Thomas knows a thing or two about engineering excitement.

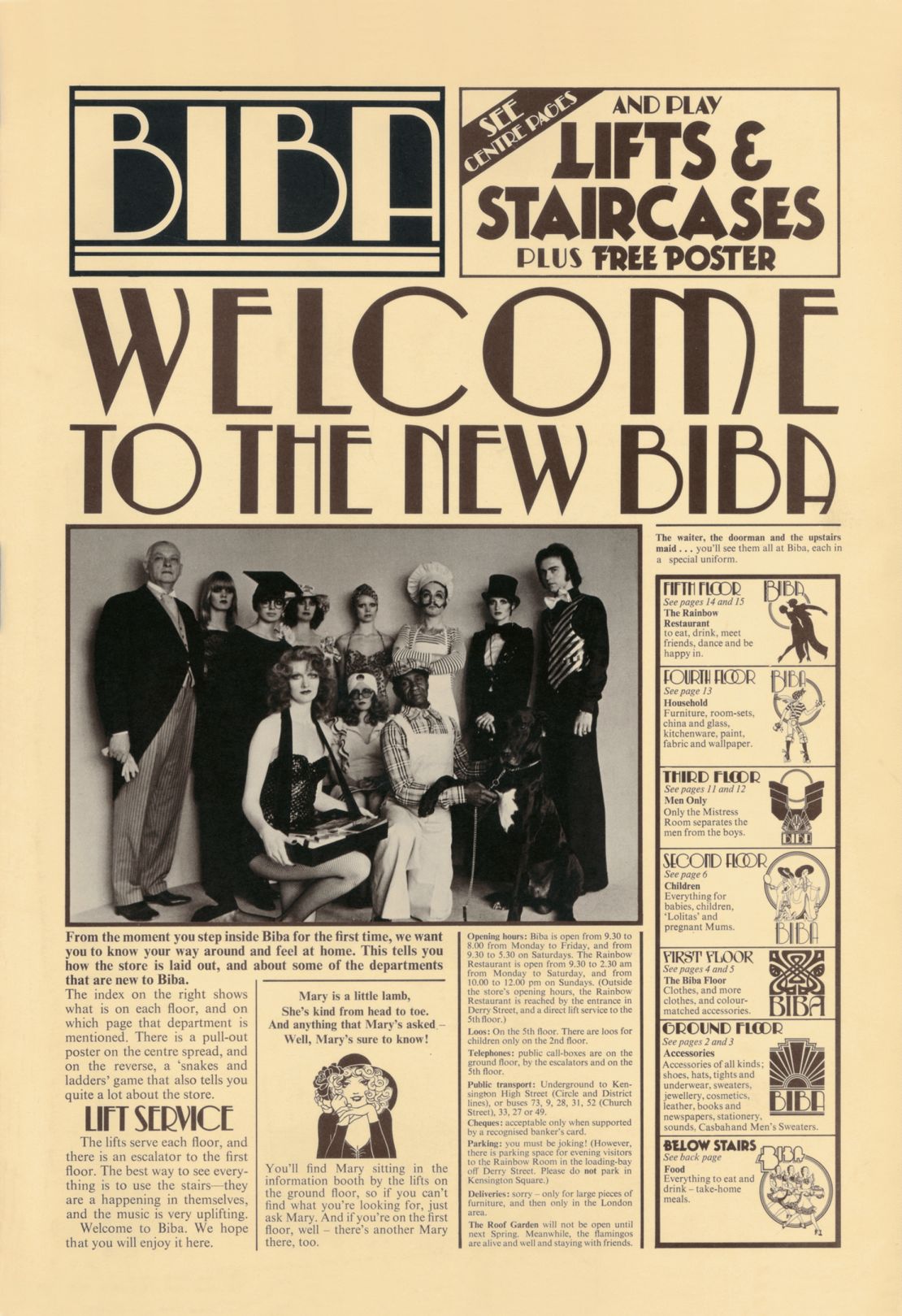

Big Biba — a daring, 20,000 square foot destination by fashion illustrator Barbara Hulanicki and her former marketing executive husband, Stephen Fitz-Simon — was conceived with a level of detail usually reserved for high-end concept stores.?Opened in September 1973,?it was the?fourth and final outpost of the-then iconic brand.?The?seven-floor Art Deco emporium on London’s fashionable Kensington High Street featured?a soup stand inspired by Andy Warhol, a roof garden featuring real flamingos and penguins, and a much-lauded celebrity hotspot the “Rainbow Room”.

“Because the Rainbow Room looked the way it did, it didn’t take long for the glitterati to latch on; it was very much a place to be seen dining,” recalled Thomas in an interview with CNN. Originally designed by architect Marcel Hennequet in 1933 and named after its multi-colored ceiling (the dining room was otherwise all white tablecloths and fake plants), it “became a venue of choice,” he suggested. “David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Bryan Ferry all dropped in.”

“Fitz employed the son of a friend who had an extraordinary knack of picking people up, like Ian Dury and the Blockheads,” continued Thomas, recalling the unofficial booker. “He got the New York Dolls to play when they came over, another coup. They did a vandalizing tour of the first floor, shoplifting all the women’s clothes.”

These stories and more are all explored in “Welcome to Big Biba,” Thomas’s gold-fronted monograph of the venture republished this month by ACC Art Books to celebrate the brand’s 60th anniversary. “This book is a testament to creative freedom,” writes the now 87-year-old Hulanicki in the foreword, reflecting on her legacy. “You can do it all as long as you learn to wear a suit. Of course, your secret will be that the suit is lined in gold lamé.”

Making fashion democratic

The Biba story began in May 1964 when Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon began running “Biba’s Postal Boutique,” a mail-order store selling limited runs of stock. Singer Annie Lennox described the venture as having led “the way for those of us living in provincial places where we felt we were dying of drabness.”

Inspired by decadent styles from bygone times — albeit with drastically shortened hemlines — in earthy or muted colors such as olive, rust and “bruised purple,” Biba’s wares certainly struck a chord with young female shoppers, and the brand rode the wave of what Thomas described as “the first burst of teenage energy and finance availability.”

“Biba made fashion democratic,” explained Martin Pel, author of “The Biba Years 1963-1975” and curator of a new exhibition at London’s Fashion & Textile Museum, in an email. “This expression is often overused of designers in the 1960s, particularly Mary Quant. Quant’s clothes whilst youthful, were expensive. Biba was inexpensive, well designed, good quality, and up-to-the-minute.”

By September 1964, Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon had opened their first brick and mortar store in a former drugstore, twice moving the business into bigger premises throughout the 60s. In 1966 the brand’s second shop on Kensington Church Street — where Vogue editor Anna Wintour famously did a stint as a Saturday girl — was described by Vanity Fair magazine as “the most exotic shop in London.” and in the early 1970s, a boutique launched in New York’s Bergdorf Goodman department store.

“An act of bravery”

Interior designer Thomas had already designed Hulanicki and Fitz-Simon’s home and the third Biba store in 1968 before being approached about the landmark seven-level store. “Fitz offered me two floors (of Big Biba) but I wanted it all,” he recalled of his initial involvement. “A moment of complete lunacy, considering Tim (Whitmore, his creative partner) and I were ex-painting students working out of my bedroom. It was an extraordinary act of bravery on their part, giving us the contract, it wouldn’t happen today.”

Stocking Big Biba’s seven floors was equal parts intimidating and invigorating said Thomas, explaining that he and Whitmore worked closely with Hulanicki throughout. “Biba was always a reflection of Barbara’s life,” he noted, “so because Barbara had a kid, of course we had a kid’s floor,” with décor inspired by Disney World, a carousel ride and miniature cottage kids café with toadstool seating. On Saturdays, an actor would visit and read stories and a crèche — a revolutionary concept in fashion retail now, let alone 50 years ago — allowed parents freedom to explore the other floors.

A maternity section and a space for 11-13 year old’s were similarly modern for the time, likewise the introduction of communal changing rooms — although true to the spirit of the times, many clients reportedly changed in the middle of the store itself.

Elsewhere menswear took over the third floor, complete with a “mistress” section for purchasing more sensual items with discretion. Biba-branded household items were upstairs. While each floor took on its own theme (maternity for example was fitted with comedic outsized furniture, inspired by Ken Russell’s 1971 musical comedy “The Boyfriend”), much of the store was furnished in Biba’s distinctive black and gold colorway, with mirrored fixtures, ostrich feathers and leopard print features.

While Wintour’s shopgirl life was short-lived, Big Biba’s staff were a vital component of the experience remembered Thomas. “They loved working there, it was their club,” he said. “And if a (customer) bought a Biba poster and stuck it on her wall, she felt part of the club. It was the theater of retail really.”

It was an unmitigated success. When the store opened its legendary roof gardens in 1974, they were ushered in by a party described in the British press as “like walking into a film set of rather jolly moral depravity.” Shoppers from all over the country, and even internationally, convened at the store to buy into the zeitgeist. According to Hulanicki, during its two-year run, Big Biba was the number two tourist attraction in the British capital after the Tower of London, with Buckingham Palace being number three.

But Biba’s success was short-lived. In 1969, the independent company sold a majority of its shares to another British fashion retailer Dorothy Perkins which, in August 1973 (a month before Big Biba opened), was then bought by a property development company called British Land. The high cost of keeping the store open and the faltering British economy of the mid-70s meant the new owners closed the store’s third and fourth floors in March 1975, and the rest of the store followed that September against the backdrop of a nationwide property slump.

Six decades on however, Biba’s legacy outlasts its footprint on the high street. Its low-cost yet well-made clothing is still coveted today, with heirloom designs sometimes retailing for hundreds of dollars. As Pel noted, “today Biba clothes stand as a lesson to both consumers and retailers that inexpensive fashion does not have to be disposable.”