From the gospel song title “We Shall Overcome” emblazoned on banners and buttons during the Civil Rights era, to the last words of Eric Garner, “I Can’t Breathe,” used in marches and social media hashtags in 2014, protest slogans have often become rallying cries that help concretize history-making movements.

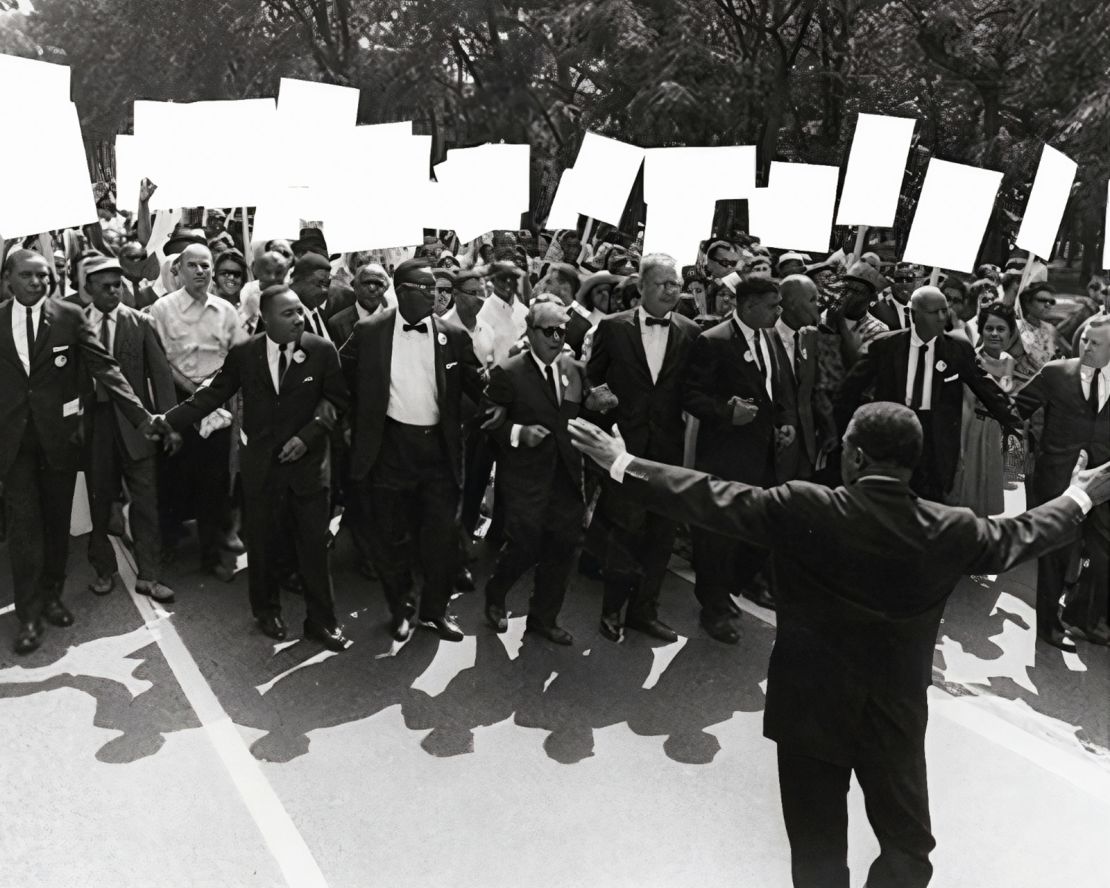

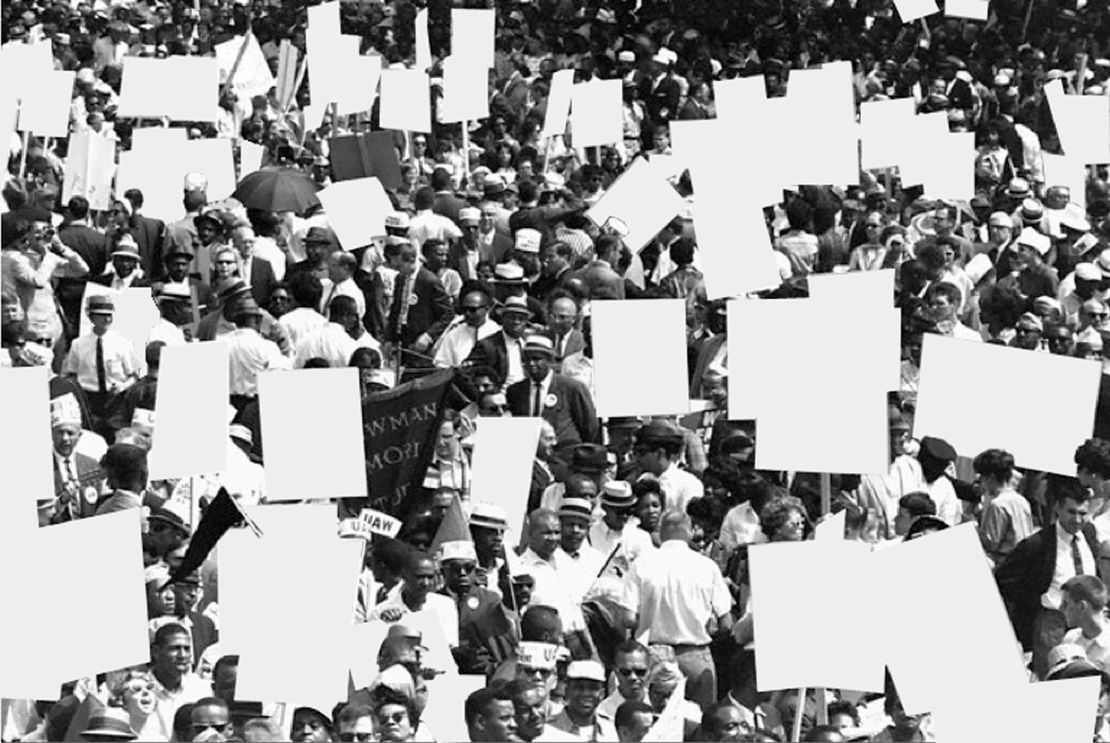

But what if that messaging was inexplicably (or deliberately) erased from our records? That’s the version of history Houston-based artist Phillip Pyle II poses in the photographic series “Forgotten Struggle,” in which he presents provocatively edited pictures of Civil Rights protestors during the 1960s carrying blank white signs. The eerie negative space on their posterboard placards abstracts the images; while they are still broadly recognizable to anyone familiar with American history, much of the crucial context is lost.

Several of Pyle’s images will be displayed at this year’s FotoFest Biennial in Houston, which opens March 9, but the artist began the series more than a decade ago in response to controversial social studies textbook changes made by the Texas State Board of Education. Since then, classroom curriculum has become a flashpoint around the country, with a tidal wave of new legislation in red states in recent years banning books and restricting topics related to race, racism and LGBTQ+ identity — and in Florida, even trying to cast some aspects of slavery in a positive light.

“The whole point of ‘Forgotten Struggle’ is that these (events) happened and now they’re trying to be omitted,” Pyle said in a phone call. “So let’s just play along.”

By creating a visual metaphor for the “whitewashing and erasure of history,” he added, he hopes to subvert the process by sparking even more interest in what appears to be censored in his images.

FotoFest’s executive director, Steven Evans, said Pyle’s work “communicates really quickly and powerfully.” It was a natural fit for the biennial’s theme “Critical Geographies,” which explore how “space, place and communities are influenced by social, economic, ecological and political forces,” Evans explained in a phone call.

The political battles being waged across education have reached a peak in Houston, where the state’s education agency took control of the city’s public schools — 274 in total — early last year, citing, in part, the consistent underperformance of a single high school. The takeover raised alarm over the state’s new power over its largest school district.

“A lot of questions about agency are happening here and about what is being taught, how it’s being taught, how resources are being allocated,” Evans said. “So I think that at a very particular level in Houston, but also at a national and international level, (Pyle’s work) is speaking to the moment.”

But Pyle’s images don’t just infer commentary on contested curriculum. For some, the images might bring to mind how misinformation spreads online,?such as?when internet users misattribute an image, edit out important context, or outright fake a photograph through AI. (Perhaps they also resemble?blank-sign meme templates,?a trope?which can be endlessly updated to keep current with the internet discourse of the day.)

For others, viewing the images?could help place historical events in a contemporary context, be an opportunity to observe lesser-seen details, or the impetus to research the source material on their own.

Pyle prefers some ambiguity, arguing that social media has created an environment where “everything can be very matter of fact” and rigid in its presentation. “You have to figure out for yourself what is going on here in this moment,” he explained of his work.

“(I want) to talk about history in a way that’s not beating you over the head with history,” he added.

At FotoFest, some of Pyle’s works will be printed large and mounted on the wall, while others will be presented in vitrines, the glass display cases that often present historical documents and artifacts in museums. But Pyle also thinks about how his images will live online, and how they might be viewed decades from now.

“I want to create these things that enter the internet zeitgeist,” he said. “In the future, somebody will come across it and be like, ‘What happened to this historical photo?’”

In that way, he hopes the work — and its glaring absences — will continue to raise questions long after our own lifetimes.