Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter.?Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more

For 265 years, more than 100 letters written by family members to the men serving aboard the French warship Galatée languished in piles, still sealed with red wax because they never reached their intended recipients.

When the ship was captured by the British in 1758 while sailing from Bordeaux to Quebec during the Seven Years’ War, the crew was imprisoned and the letters, which just missed reaching the ship, were confiscated and handed over to the Admiralty of the British Royal Navy in London.

Now, the letters have been opened and read for the first time, and their contents provide intriguingly rare historical context about a cross section of society at the time, said lead study author Renaud Morieux, professor of European history and fellow at Pembroke College at Cambridge in the United Kingdom. The study was published Monday in the French journal Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales.

“These letters are about universal human experiences, they’re not unique to France or the 18th century,” Morieux said in a statement. “They reveal how we all cope with major life challenges. When we are separated from loved-ones by events beyond our control like the pandemic or wars, we have to work out how to stay in touch, how to reassure, care for people and keep the passion alive. Today we have Zoom and WhatsApp. In the 18th century, people only had letters but what they wrote about feels very familiar.”

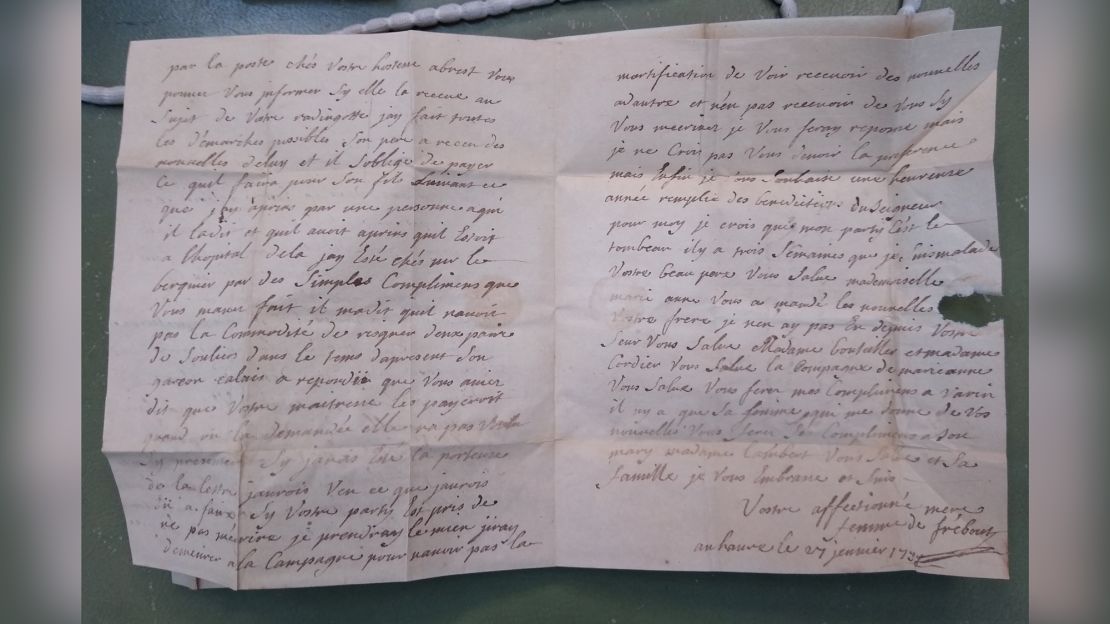

Some of the correspondences are from wives of the sailors sending love letters to their husbands, wishing they could be reunited or waiting to hear whether their loved ones were safe.

About 59% of the letters were signed by women, offering insights into literacy across classes and what life was like for those who were making key decisions at home as their husbands sailed the seas.

“I could spend the night writing to you … I am your forever faithful wife,” Marie Dubosc wrote. “Good night, my dear friend. It is midnight. I think it is time for me to rest.”

The letter was addressed to Louis Chambrelan, her husband and the first lieutenant of the ship. He never received the letter and never saw his wife again. Dubosc died in 1759, likely before he was released after being captured. Chambrelan returned to France and remarried in 1761.

“These letters shatter the old-fashioned notion that war is all about men,” Morieux said in an email to CNN. “While their men were gone, women ran the household economy and took crucial economic and political decisions.”

Reading words from the past

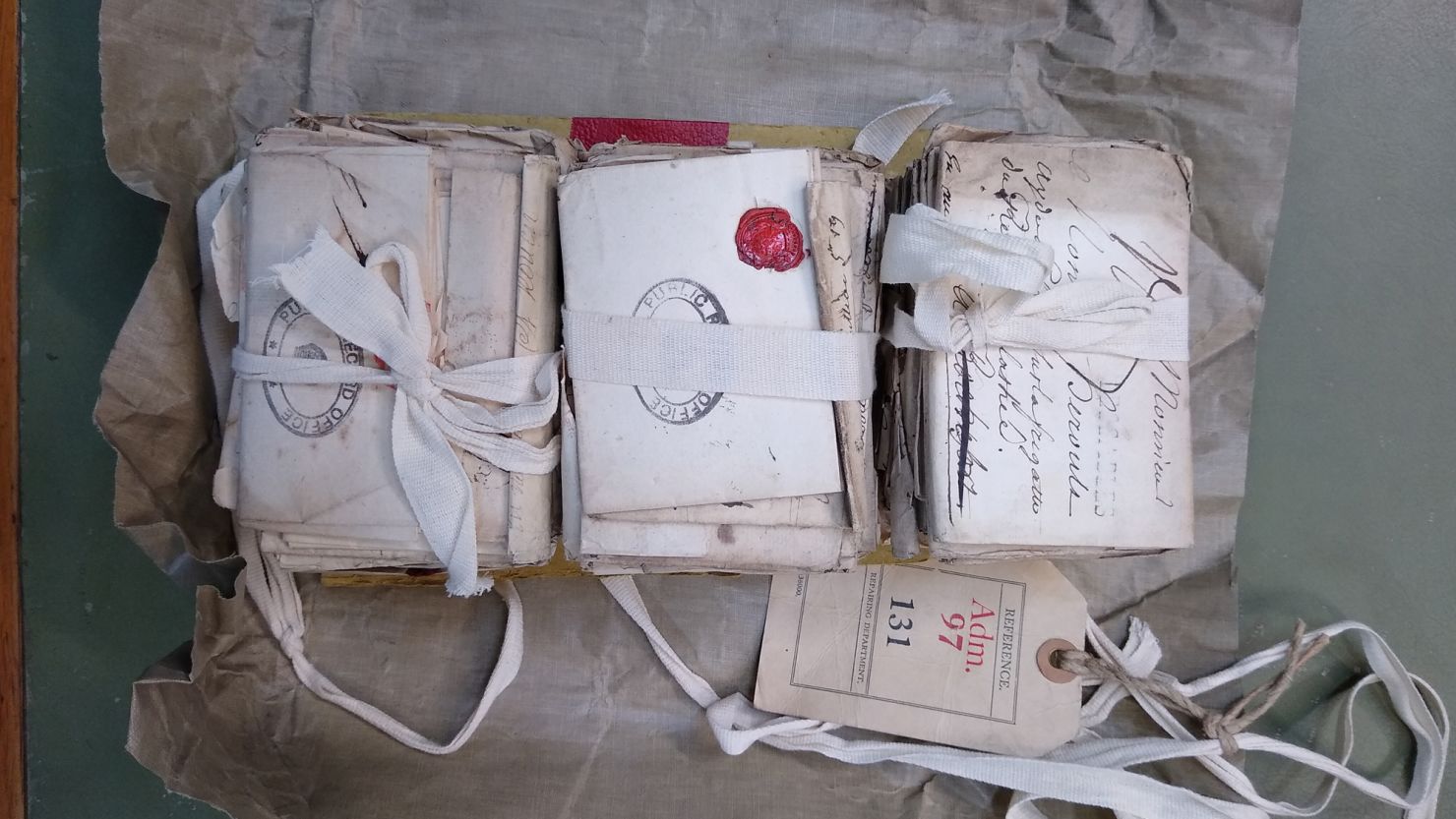

Morieux came across the box of letters at the UK’s National Archives while conducting research for his book “The Society of Prisoners: Anglo-French War and Incarceration in the Eighteenth Century.”

Inside, the letters were bundled together with ribbon. Seeing that the small letters were still sealed, he asked whether correspondence could be opened and was granted permission. Unsealing the letters was “like finding a treasure box,” he said.

“They were almost waiting for me to open them. Being the very first reader of letters that were not addressed to me is a unique experience,” Morieux said.

The French postal administration originally tried to deliver the letters to the ship, sending them around to multiple ports before learning the ship had been captured and sold. While the French had impressive ships, they lacked experienced sailors, so the British captured as many as they could, Morieux said. Britain’s forces captured and imprisoned 64,373 French sailors over the course of the Seven Years’ War.

Some prisoners of war died from malnutrition or disease, but many were released later. However, their families faced an agonizing uphill battle in trying to get in touch with the men and learn their fates. Before being captured, the Galatée was in Brest, France, which was hit with a typhus epidemic.

Understanding that it might be difficult to reach their loved ones, family members might send multiple copies of one letter to different ports or ask the families of other crew members to include a mention in one of their letters.

“They give us a sense of the resilience of societies in times of distress and challenges,” Morieux said. “The letters also tell us about the creativity of people to overcome the challenges of distance and absence: they had to rely on others, such as family, friends and neighbors, to send and receive information.”

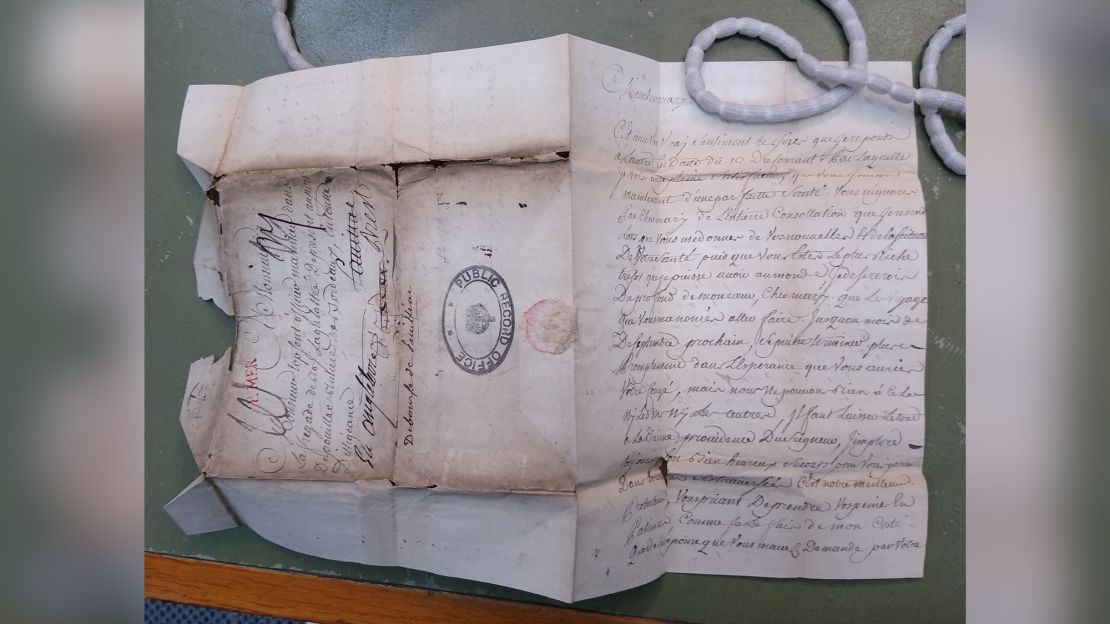

Morieux believes that British officials opened and read the contents of two of the letters to see whether they contained any useful information. But when the missives were only found to contain “family stuff,” the lot was placed in storage.

Decoding the letters

Morieux spent months reading the letters, which contain an array of misspellings, cramped handwriting covering every inch of paper, and little punctuation. He also identified every member of the 181-man crew of the ship, determining that the letters were addressed to about a quarter of them.

Morieux was particularly captivated by a saga detailed across several letters: He uncovered missives from a mother anxious to hear directly from her son and others from his fiancée, who was stuck in the middle in an age-old family dynamic.

The mother had used a scribe to send letters to her son, young sailor Nicolas Quesnel, complaining that he wrote more to his fiancée than her.

“On the first day of the year (i.e. January 1st) you have written to your fiancée (…). I think more about you than you about me. (…) In any case I wish you a happy new year filled with blessings of the Lord. I think I am for the tomb, I have been ill for three weeks. Give my compliments to Varin (a shipmate), it is only his wife who gives me your news,” his 61-year-old mother Marguerite included in her letter.

Quesnel’s fiancée, Marianne, pleaded her future mother-in-law’s case in a separate letter to avoid awkwardness because Marguerite seemed to blame Marianne for the silent treatment from her son.

“The black cloud has gone, a letter that your mother has received from you, lightens the atmosphere,” Marianne wrote.

But Marguerite returned with other complaints. “In your letters you never mention your father. This hurts me greatly. Next time you write to me, please do not forget your father,” his mother’s letter read. Marguerite referred to his stepfather, whom she married after Quesnel’s father had died.

“Here is a son who clearly doesn’t like or acknowledge this man as his father,” Morieux said. “But at this time, if your mother remarried, her new husband automatically became your father. Without explicitly saying it, Marguerite is reminding her son to respect this by sharing news about ‘your father.’ These are complex but very familiar family tensions.”

New insights into literacy

Several letters included information to convey that they were written by scriveners, or those who would read and write on behalf of another. The scriveners might even include a message, such as “the scrivener salutes you,” in the middle of a letter.

“One didn’t have to know how to write or to read in order to participate in epistolary culture,” Morieux said. “The letters tell us about a strange time when notions of the private and the public were not totally separate, as they are today: one could talk about love, even express physical desire for one’s husband … in a letter dictated to someone else, or that would be read by others.”

One example was a letter from Anne Le Cerf to her husband, an officer on the ship. “I cannot wait to possess you,” she wrote, which could mean “embrace” or “make love.”

Morieux is interested in uncovering more information about the crew and what happened to them, and to see whether he can find letters they wrote while imprisoned. The contents of the letters written to the crew of the Galatée have fascinated him, and he wants to keep pulling that thread.

“It is pretty rare for historians to find documents that were written in the first person by people below a certain social class — at least before the twentieth century, when more and more people could read and write,” he said. “Getting access to the writings of women, especially sailors’ wives, is exceptional. This allows us to glimpse at their emotions, fear, anxiety, anger, jealousy, as well as their faith or the key role they played in the running of the household while their husband, son or brother was absent.”