Editor’s Note: Sara Novic is a deaf writer and the author of the books “True Biz,” “Girl at War” and “America is Immigrants.” The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

This week, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finalized a rule change that would create a class of over-the-counter hearing aids, available for purchase without a prescription or fitting from an audiologist. The change came after a years’-long wait – Congress passed a bipartisan bill on the matter in 2017 – with many hailing the news as a great relief for millions of deaf and hard-of-hearing Americans who often find these expensive medical devices out of reach.

For those who, like me, actually have experience with hearing aids, this shift is more complicated. The FDA’s recent changes do help some, but they also present potential dangers for consumers and spotlight large gaps in care remaining for many who need it most.

Notably, while coverage of the new rules has been dotted with images of cute babies in hearing aids, they apply only to hearing aids for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. Still, the move undeniably makes hearing aids accessible for a subset of the population who needs them, and I’m happy to know that this decision will help those people.

But as a deaf person, I’m wary that the FDA, and our elected officials who voted on the related legislation over five years ago now, might see this as a box to be checked off a to-do list, and forget about the rest of us who are not aided by this change. Those like me who require higher-powered devices will still be forced to pay out-of-pocket. No children will benefit from the new category of aids.

Our society has a tendency to support the disabled in surface-level ways, retrofitting narrow solutions while continuing to shy away from the systemic moves that would make things better for everybody. Hearing loss is a very prevalent disability, with one in eight Americans over age 12 experiencing some degree of loss. By age 75, that number increases to nearly half the population. But according to one survey by the American Speech and Hearing Association, only 20% of people with hearing loss who need treatment actually receive it, with most waiting more than 10 years after diagnosis to be fitted with aids.

In the US, barriers to acquiring hearing aids are manifold. Hearing aids are not covered by Medicare, nor most private insurances, and state-specific Medicaid coverage varies. Without coverage, a single aid might cost up to $5,000 depending on technology, and this is to say nothing of the bills for the multiple doctors’ visits to obtain referrals, testing, prescriptions and follow-up care to fine-tune the hearing instruments.

In rural and low-income areas, access to audiologists or ENT (ear, nose and throat) doctors is often limited, forcing patients to endure long drives or extended wait times before they can be seen. It’s understandable, then, that many people might find themselves unable or unwilling to be treated.

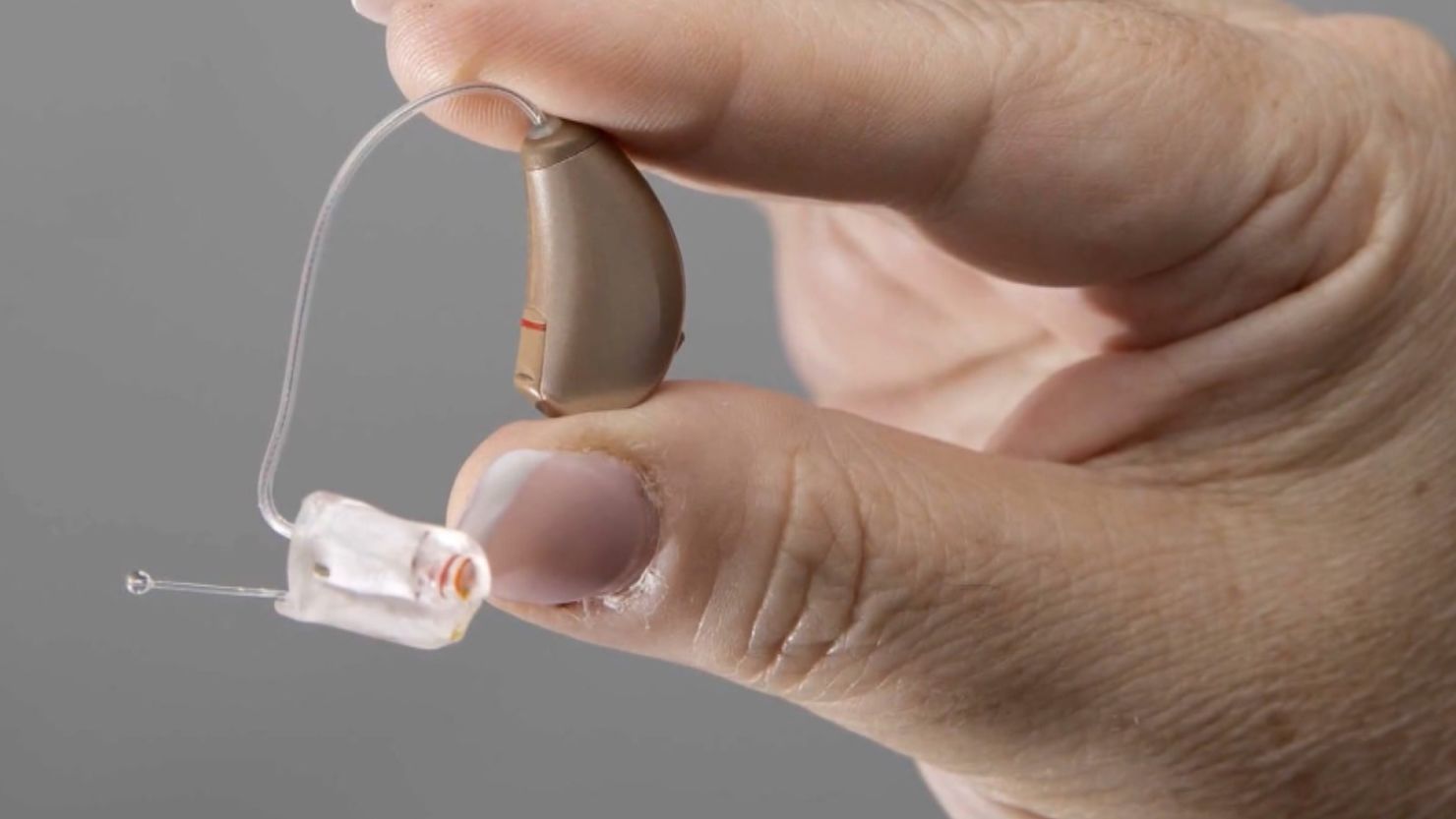

Some have likened the creation of a class of over-the-counter hearing aids to buying a pair of reading glasses off the rack at a pharmacy, but the comparison is ultimately misguided. Just as far-sightedness is one of many types of vision issues, there are different types of hearing loss, most of which require more nuance than simply making something louder. “Normal” human hearing requires the simultaneous function of the outer, middle and inner ear, as well as the auditory nerves that bring that information to the brain, and the brain’s processing centers themselves. A doctor’s evaluation is valuable to pinpoint the source of a problem with one’s hearing.

A hearing aid best serves those with sensorineural hearing loss, the death of the inner ear’s cochlear hair cells. This is the leading cause of hearing loss, particularly among the elderly, but it’s not the only kind, and only testing by an audiologist would be able to differentiate. Those in need of treatment for other kinds of hearing losses may not only find hearing aids unhelpful but may damage their cochlear cells by listening at a heightened volume over an extended period.

Additionally, even for those who have sensorineural hearing loss, a hearing aid is certainly not a one-size-fits-all solution. A person’s loss is rarely the same across all frequencies – most elderly people, for example, hear low sounds better than higher ones. When a person is fitted with hearing aids by an audiologist, the doctor programs the aids at each frequency level with respect to the patient’s unique needs. Many hearing aids also have programs to be used in different settings, like one for watching television, and another for a noisy restaurant, which change sound levels and mitigate background noise in a way that is also tailored to suit an individual’s hearing levels.

Proponents of the FDA changes say that increasing competition among hearing aid manufacturers will encourage technological innovation, including increasing self-adjustment capabilities, but in the interim, it’s likely that new hearing aid users might experience pain from too-loud sounds at some frequencies, or would continue to struggle in situations with a lot of background noise. This might lead to a decreased desire to adopt the technology long-term, even as general access increases overall.

Finally, there is the question of stigma. While wearing eyeglasses is generally understood to be part of a standard variation of human experience and appearance, and is sometimes even considered trendy, pervasive ableism and ageism often stigmatize hearing aid users. Even with increased availability, I expect it will take some active and conscious dismantling of these negative stereotypes before we see a meaningful uptake in hearing aid use.

The positives surrounding the changes in hearing aid guidelines amount to a lot of hope for the future, but not much concrete support for those in need. Undoubtedly, those adults with mild sensorineural hearing loss for whom aids were previously too expensive will be better off for the changes. As for all the optimism we invest in the free market regarding innovation and overall price decreases due to competition, only time will tell. Ultimately, these changes feel a bit like a band-aid on the gaping bullet wound that is the American health care system. Instead of equitable access to care for all, we see the piecemeal doling out of do-it-yourself measures to some and are expected to celebrate.

And I do celebrate with those for whom a bandage can stop the bleeding. I also hope that they, and everyone, will continue to stand with fellow deaf and hard-of-hearing Americans and advocate for equitable access to hearing technology for all those who need it.