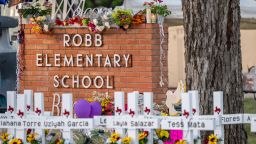

The release this week of 82 minutes of school surveillance video from the May massacre in Uvalde, Texas, is fueling scrutiny over what, if any, consequences officers might face for their decision to retreat from gunfire and wait an hour to confront the shooter inside the school where he killed 19 fourth-graders and two teachers.

The much-anticipated Texas House Investigative Committee’s preliminary?report into the most deadly American school shooting in nearly a decade is expected soon, though it’s not clear how wide-ranging the panel’s work has been or what might result from its probe.

So far, the person said to have been in charge during the May 24 shooting – the school district’s police chief, Pedro “Pete” Arredondo – has been slammed by the slain children’s parents, local elected leaders and fellow law enforcement officials who claim he failed to follow training and wrongly delayed entry for more than an hour into the classroom where officers killed the gunman. Armed officers from several agencies milled about while the gunman was free to move around adjoining classrooms, the video published by the Austin American-Statesman shows.

Arredondo – who’s said he neither considered himself the incident commander nor instructed officers to refrain from breaching the scene – resigned the Uvalde City Council seat he assumed just a week after the attack. But formal repercussions for him – and any others from at least eight agencies involved in the police response – remain largely elusive.

The consequences could be criminal, administrative or civil. But varying standards in each of these jurisdictions and conflicting rules governing investigations reflect “a persistent problem in police accountability,” said Seth Stoughton, professor of law at the University of South Carolina.

“It’s not just this case – it’s in many cases.” Competing priorities, he said, might pit whether it’s “more important to figure out what happened or to figure how to avoid it in the future. Or more to hold an officer individually liable in some way, criminally or civilly. They can run right smack into each other.”

Also investigating the attack at Robb Elementary School is the Texas Department of Public Safety. But publicly, at least, it’s unclear precisely which facets of the incident it’s delving into and which standards it’s trying to uphold – to say nothing of what the probe might yield. Similar questions linger over inquiries other agencies might be undertaking.

The Department of Justice also is investigating the shooting, aiming to “provide this definitive, independent accounting,” Associate Attorney General Vanita Gupta said in June on C-SPAN. The review “is not a criminal investigation,” she added.

Many of at least eight agencies whose officers responded to the school that day haven’t responded to CNN’s requests for comment. Others have declined to answer questions about their role in the emergency response.

Officials’ repeated revisions in the case narrative since the hours immediately after the attack have made a true and full understanding of the law enforcement response impossible so far. And given the fraught backdrop of American gun violence against which the facts are unfolding, it’s unclear what consequences may result.

Still, what’s known in this case and of general policing standards suggest this is what the fallout for officers could look like:

Criminal charges for failure to act unlikely, experts say

The crux of the police response that’s captured utmost public attention is the time that passed with the shooter alive in the school: at least 70 minutes.

It’s unlikely criminal charges would be filed against responding officers – and more unlikely they would stick – over alleged inaction or allegations they didn’t quickly enough kill the shooter, Stoughton told CNN.

Prosecutors have discretion in filing charges, so it’s not impossible, but the bar is high for criminal accountability for inaction.

?“We only punish an omission – a failure to do something – when there’s a specific legal requirement, a legal duty, for someone to do what they’ve failed to do,” Stoughton said.?“Here, what we’re looking for is legal duty that required officers to go in earlier than they did. And I’m not aware of one.”

After the Parkland, Florida, high school massacre, a prosecutor charged an officer under a state “caregiver” law for an alleged failure to act during the shooting that left 17 dead. He has pleaded not guilty to seven counts, with a trial set for 2023.

“The caretaker statute applies to teachers: They have to affirmatively safeguard (the) well-being of kids. Because he’s a school resource officer, the prosecutor is arguing the statute that applies to caregivers counts because he’s, arguing (the officer) is in position like a teacher,” Stoughton said.

“It is a bit of a stretch,” he allowed, “and we don’t even have that” in the Uvalde case.

Indeed, it’s not clear if any particular law in Texas would have obligated such an officer to act in any specific way, he said. It’s also not clear if any prosecutor is considering insufficient action by law enforcement.

As to finding criminal fault with officers’ actions that day, prosecutors are in a “really difficult position,” said Carol Archbold, chair of the criminal justice department at North Dakota State University.

“The odds are slim that they would actually bring charges and have the charges stick,” she said. “This is involving children, loss of life of children, which is tragic. … There’s something that sparks outrage or an outcry for accountability from the public because it’s involving children.

“So, prosecutors are put in a position where they have to obviously follow the law but at the same time have to deal with balancing public opinion or outcry,” she told CNN.

Scope of administrative reviews is unclear

When an officer fires their gun or responds to a chaotic mass-casualty incident, police departments typically conduct internal reviews or invite third parties to do so, with their sights set on determining whether departmental rules were followed before and after the event and the roles each officer played. Most police departments also have broad “conduct unbecoming” rules, and agencies may also have specific active-shooter protocols or other written standards.

“Conduct unbecoming” clauses typically would be the easiest way for an agency to discipline officers, Stoughton said.

“In some ways, that’s the easiest to imagine in a case like this because all they have to do to be administratively liable, sanctioned or disciplined is violate policies or training,” he said. “And even if no specific policy that says go in there get active shooter, they can say, ‘Look … you’re trained to do a thing, you didn’t do that thing, you didn’t do what you’re expected to do.’”

But even that depends on whether lower-ranking officers were ordered to wait, he said.

While it’s not clear what type of training or orders regarding active shooter incidents each Uvalde responding agency has, consequences in general for violating such law enforcement rules range from a verbal scolding to being fired. Disciplinary processes usually give officers a chance to contest allegations. And even termination can be uncertain: At least one deputy who responded to the Parkland school massacre and was fired for inaction got his job back after his union contested the firings.

Arredondo, for his part, was placed on administrative leave June 22.

While much of the public focus after the Uvalde mass shooting has been on whether officers moved quickly enough into the classroom where some eventually killed the shooter, administrative reviews also could look at whether officers followed training and orders before going in and how they handled information and evidence afterward.

At least three federal, two state and three local agencies responded to the carnage at Robb Elementary – but it’s not clear which may be conducting such investigations or their status.

“It’s good that you have different set of eyes looking at the case because they’re likely to find something another agency or individual didn’t find,” Archbold said.

“I’m not really sure what’s going to happen or how long it will take, but given so many people are looking, at some point we’re going to learn what happened,” Archbold said. “It just may not be quickly.”

Meantime, an examination of who’s looking at what reveals a tangle of interests: The district attorney’s investigator in Uvalde County, for instance, was part of the police response on May 24, along with the state police agency – the Texas Department of Public Safety – which is handling the broader criminal investigation. And the state legislative committee is relying on testimony from department personnel in producing its report.

It’s not clear if those two agencies are subject to any outside scrutiny that could result in administrative accountability or whether there are internal investigations into their officers’ conduct that day. The county district attorney declined to comment, and a spokesperson for the Texas Department of Public Safety and the Texas Rangers didn’t respond to a request for comment. Spokespersons for the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District Police Department, the school district itself and the Uvalde Police Department also didn’t respond.

The Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center at Texas State University is producing after-action reports with the “explicit purpose of identifying training gaps to be addressed by police officers across the state of Texas.” But it’s not clear whether any agencies with officers on scene that day will use those reports in seeking administrative action against officers. The agency trains first responders across the country in response to “active attack situations.”

Civil lawsuits mean a high bar for plaintiffs

Civil litigation may be another way families of victims could seek accountability.

So far, a state legislator in Texas has sued for access to public records related to the mass shooting, and the families of four victims have sued the estate of the shooter. It appears no lawsuits have been filed against law enforcement in which the claim relates to the quality of the police response, though a San Antonio attorney said in late June he plans to file such a suit by mid-July.

If they’re sued, agencies could settle in a way that shields them from having to make any public statements about their role in responding to the shooting. But if government agencies fight any suits, the bar for holding officers liable for inaction would be high, Stoughton said.

It isn’t just that officers didn’t act, he said: They had to have made it worse.

“These are really tough cases, though, because the standard the Supreme Court has set for failure to protect is that police – government generally, but here, police – the only legal duty to protect is when police themselves create the danger or make it worse.” Stoughton said.

Not acting – in this case, not confronting the gunman sooner – isn’t typically sufficient for a civil claim to result favorably for the plaintiff, he said.

Grieving Uvalde families have condemned police as “cowards,” and parents have expressed worries about children who survived but couldn’t save their friends. But it’s not clear if those conclusions would be enough to yield a win in court against a police agency.

“The easy way to understand this is: Did police create the danger or make the existing danger worse?” he said. “Not just did they allow it to occur, but did they make it worse?”

Federal review aims for ‘lessons learned’

While the Department of Justice is helping local authorities investigate the massacre by providing expertise and processing evidence, the goal of its “Critical Incident Review” is to document “lessons learned and best practices” for first responders.

“I want to be clear: This is not a criminal investigation,” Gupta said in June. “Obviously, the department has criminal investigative authority, and we prosecute officers for violating the law when that happens, but this is an after-action review, which is another tool that the department has … to be able to provide a definitive accounting.”

The federal agency will look at video and other evidence to “reconstruct the timeline,” looking at what happened before, during and after the massacre to “provide this definitive, independent accounting,” she said, reiterating: “It is not a criminal investigation.”

CNN’s Meridith Edwards, Josh Campbell, Rosa Flores, Omar Jimenez, Jamiel Lynch, Rosalina Nieves, Hannah Rabinowitz, Rebekah Riess, Amy Simonson and Whitney Wild contributed to this report.