“What would happen if we cut off your ear?” the soldiers asked Oleksandr Vdovychenko. Then they hit him in the head.

The punches kept coming whenever his interrogators – a mixture of Russian soldiers and pro-Russian separatists – didn’t like his answers, he later told his family.

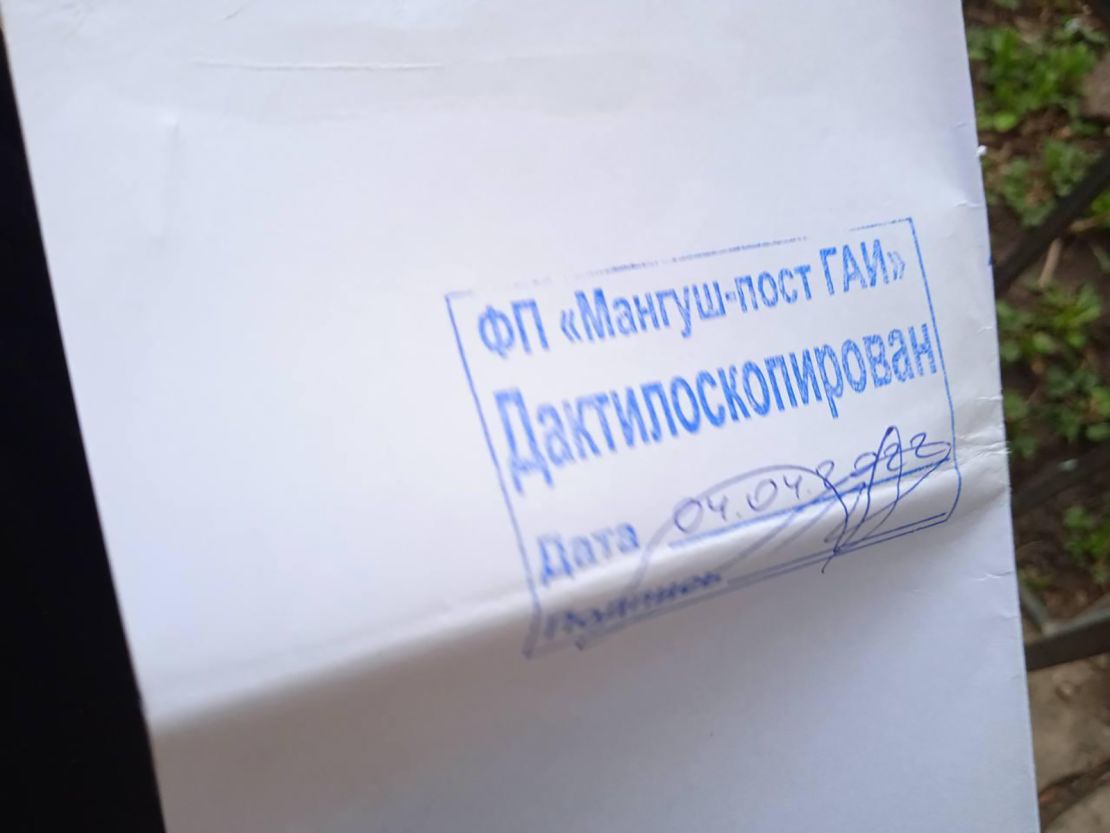

The men asked about his politics, his future plans, his views on the war. They checked his documents, took his fingerprints and stripped him to check if he had any nationalist tattoos or marks caused by wearing or carrying military equipment.

“They were trying to beat something out of him,” his daughter Maria Vdovychenko told CNN in an interview.

Maria said her father received so many blows to his head during the interrogation last month that several medical examinations have now confirmed his sight has been permanently damaged.

Yet Oleksandr was one of the lucky ones. He made it through “filtration.”

When Russian troops first started taking over villages and towns in eastern Ukraine in early March, following their invasion of the country, evidence began to emerge of civilians being forced to undergo humiliating identity checks and often violent questioning before being allowed to leave their homes and travel to areas still under Ukrainian control.

Three months into the war, the dehumanizing process known as filtration has become part of the reality of life under Russian occupation.

CNN spoke to a number of Ukrainians who have gone through the filtration process over the last two months. Many are too scared to speak publicly, fearing for the safety of relatives and friends who are still trying to escape Russian-held areas.

All of the people CNN spoke to have described facing threats and humiliation during the process. Many have witnessed or know of people who have been picked up by Russian troops or separatist soldiers and subsequently disappeared without a trace.

For most of the people CNN spoke to, the filtration process included document checks, interrogation, fingerprinting and a search. Many were separated from their families. Men were routinely stripped and examined.

Lyudmyla Denisova, the Ukrainian parliament’s human rights ombudsman, said earlier this month that Russian forces had created an “extensive network” of places where Ukrainians are being subjected to “filtering.”

She said such places have been established “in every occupied Ukrainian city” and that more than “37,000 citizens” have already gone through the procedure.

Nikolay Ryabchenko told CNN he fled Mariupol in mid-March when the city was closed and people were not allowed to move around.

“We found a way to avoid checkpoints and came to Nikolske and we stayed there for a couple of weeks,” he said. “I asked everyone I met how to get out and they [said] filtration is obligatory.”

Information signs that have been posted in Mariupol after Russian troops took over the city leave no room for doubt: “Evacuation can be carried out if there is a document confirming the passage of the filtration procedure.” CNN has seen a photo of one such sign taken by a person who escaped the city.

“Everyone has to go through filtration, both men and women, in order to move around the city freely,” 20-year old Karina, another Mariupol resident, who is only being identified by her first name due to security concerns, told CNN.

She has managed to escape Mariupol but her father, who has not yet passed the filtration process and has no idea why, is still there.

A month after being picked up by Russian soldiers on a street in Mariupol, he is still being held in what the self-declared separatist Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) in eastern Ukraine calls a “reception center” at a school in Bezimenne, around 20 miles (32 kilometers) east of Mariupol, he told his daughter.

The separatist-held Bezimenne has been used by Russian troops as a screening facility for refugees from Mariupol and surrounding areas.

In three separate statements published last week, the DPR Territorial Defense said almost 1,000 evacuees from Mariupol have been brought to the Bezimenne center in a three days. It said that as of May 17, more than 33,000 people have gone through the facility.

Earlier this month, the Russian Ministry of Defence released a video showing evacuees from Mariupol arrive in a filtration camp outside the city in busses. The ministry published the videos without saying where the refugees were taken, or when the evacuations took place. CNN has been able to geolocate the footage, and it shows that they were taken to Bezimenne.

Separately, satellite images from Maxar Technologies have showed a tent encampment being erected in the separatist-held Bezimenne as early as in March.

Karina said she had been able to speak to her father who told her that conditions there were appalling.

“Some sleep on the floor, some are luckier [and sleep] on chairs, and some are even luckier and have mattresses in the gym,” she said. “There’s no opportunity to wash and no normal restroom. All of them were ill because it was too cold to sleep on the floor.”

Karina said her father had told her the guards in the center have refused to provide any medicine to the people being held there. They are being fed watery soup and other prison-like food cooked in a field kitchen, he said.

Ombudsman Denisova said the Bezimenne center where Karina’s father is being held is just one of several such facilities set up in the Donetsk region. She said Russian troops have established similar filtration camps in Dokuchaevsk, Mykilsky, Mangush, Bezymenny and Yalta.

She accused Russia of using the centers to detain and “wipe out” any “officials, members of the military or the volunteer territorial defense forces, activists or anyone they consider a threat.”

Maria Vdovychenko told CNN it looked like the soldiers were trying to find anything they could say was incriminating.

“They were looking for Ukrainian-speaking people, for Ukrainian symbols, tattoos,” she said, adding that the soldiers checked her phone, but didn’t find anything compromising.

“We have deleted everything because people in the line told us they can look at everything – contacts, for example, they could call some of your contacts – and pictures … For every Ukrainian, it is normal to have pictures in vyshyvanka [traditional Ukrainian embroidered clothing] or with a flag, or near [a] Shevchenko monument [depicting prominent Ukrainian poet, Taras Shevchenko],” Maria said.

“I’m a bandura [traditional Ukrainian instrument] player, it wasn’t good idea to show that. So I deleted that, took a couple of new pictures, and deleted my social network profiles,” she added.

Michael Carpenter, the US Ambassador to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), said last month there was credible reporting that “Russia’s forces are rounding up the local civilian populations in these areas, detaining them in these camps, and brutally interrogating them for any supposed links to the legitimate Ukrainian government or to independent media outlets.

Speaking last week, Carpenter added: “Numerous eyewitness accounts indicate that ‘filtering out’ entails beating and torturing individuals to determine whether they owe even the slightest allegiance to the Ukrainian state.”

Mariupol city council has accused Russian forces of using the filtration centers to identify witnesses to any “atrocities” committed by Russian troops during the battle for the control of the city. CNN could not verify that claim.

The Kremlin has denied using filtration camps to cover up wrongdoing and targeting civilians in Mariupol.

The self-declared DPR has denied accusations by Ukrainian authorities of unlawful detentions, filtration and maltreatment of Ukrainian citizens and said that those arriving at what it calls reception centers are properly fed and provided medical attention.

Karina said that, according to her father, most of the men in the center have no idea why they are being held.

“They were told the filtration would take one to two days maximum and that the [process] is needed to check if they took part in hostilities,” Karina told CNN. “They have been trapped there since April 12 and have no idea when they will be released.”

That uncertainty makes the process terrifying for Ukrainians trying to flee to safety. Most have no idea what to expect.

Ukrainian social media pages for people stuck in Russian-controlled regions, or their families searching for them, are full of questions about filtration.

Yana, who left Berdiansk in southern Ukraine to stay with relatives in Rostov in Russia, the only place she said she was able to get to, said the process appeared to be completely random. She asked CNN not to publish her last name, fearing retribution.

“Close friends told me that they stood in line for filtration for six days, spent the nights in cars, and yet some passed quickly. I don’t know why – apparently it depends on which shift you will get,” she said.

Before the war, Eugen Tuzov was a martial arts instructor in Mariupol. Now he spends most of his time trying to organize transport for people stuck in the Russian-occupied city and the surrounding areas who want to flee to places under Ukrainian control.

He, too, told CNN the filtration process at checkpoints on the roads leading out of Mariupol – he said there were at least 27 of them – appeared to be random.

“Everything depends on [the] shift. Someone is lucky, someone comes to a sh*tty shift,” he said.

“The DPR people were the worst – they are disheveled, slovens, sometimes they are drunk already in the morning, behaving terribly. You see man 50, 60 years old and you can see it from his face that he drinks constantly,” Ryabchenko told CNN.

Petro Andriushchenko, an adviser to the Mariupol mayor, said in a statement on Monday that Russian troops have set up five filtration points across the city.

Mariupol residents need to pass this procedure in order to receive a certificate allowing them to move around the city, he said, adding: “If this isn’t a ghetto, I don’t know what is.”

Yana said her parents had to undergo filtration at a hospital in Donetsk, where they were taken after being wounded in a strike, having already spent more than two weeks hiding in a shelter in Mariupol with no medical help.

“People came from some service, took their fingerprints, told them this is filtration since they could not walk, but it had to be done, such rules are in the DPR,” she said.

Yana said when she and her husband drove out of the area, they had to pass almost 20 checkpoints. “And at almost every checkpoint, they undressed my husband, looked for tattoos and weapons marks and asked whether he had served in the army,” she said.

Tuzov said the volunteers in his transport service have similar experiences; he said some were subjected to lie detector tests and that – as far as he knows – at least 30 of them were detained during the process. “They were taken at checkpoints. They check phones, social networks, if you wrote something about them … they take you away,” he said.

Tuzov said he doesn’t know the fate of those who have been detained. CNN has previously reported that some of those picked up in the process end up being sent to Russia.

Maria Vdovychenko said she and her family – her parents and younger sister – waited in Nova Yalta for about 20 days before they were allowed to go through the filtration process.

“We were told we wouldn’t be able to get out without that,” she told CNN. “They [said] they will just check documents and phones, and we will leave. But it wasn’t as easy as they promised.”

She said the family queued for two days and two nights without being allowed to leave their car. Finally, Maria and her father were taken to a small wooden structure about 200 meters away. Her younger sister and her mother, who wasn’t able to walk, were told to stay in the vehicle.

While waiting to enter the makeshift building, Maria said she felt threatened. “[The soldiers] were talking among themselves. It was scary to listen to what can happen to people who didn’t pass the filtration. I will remember it forever.”

She said she overheard one of the soldiers guarding the site saying: “‘I killed 10, and didn’t count further.”

The reports coming from these facilities have shocked the international community and the practice was cited as one of the reasons for Russia to be suspended from the UN’s Human Rights Council in April. Despite the outrage, evidence from the ground, testimonies from those who escape and statements by the separatist authorities show Russia has only increased its use of filtration since then.

It’s not the first time either. During the war in Chechnya, Russian forces used filtration camps to separate civilians from rebel fighters. Legendary Russian investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya gathered testimony from Chechen civilians detained these centers, revealing brutal interrogation methods, torture and human rights violations. She was murdered in her Moscow apartment building in 2006.

CNN’s Tim Lister, Olga Voitovich, Mariya Kostenko, Anastasia Graham-Yooll, Jennifer Hansler, Eliza Mackintosh and Oleksandr Fylyppov contributed reporting.