Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

When the United States, Japan, Australia and India first resuscitated their informal dialogue from a decade-long hiatus in late 2017, China was confident it would soon fail.

“It seems there is never a shortage of headline-grabbing ideas,” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said dismissively of the grouping in early 2018, months after it convened its first working-level meeting in Manila.

“They are like the sea foam in the Pacific or Indian Ocean: they may get some attention, but soon will dissipate,” Wang concluded.

More than four years on, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – better known as “the Quad” – is far from dissipating. Instead, it has only grown in momentum, profile and clout.

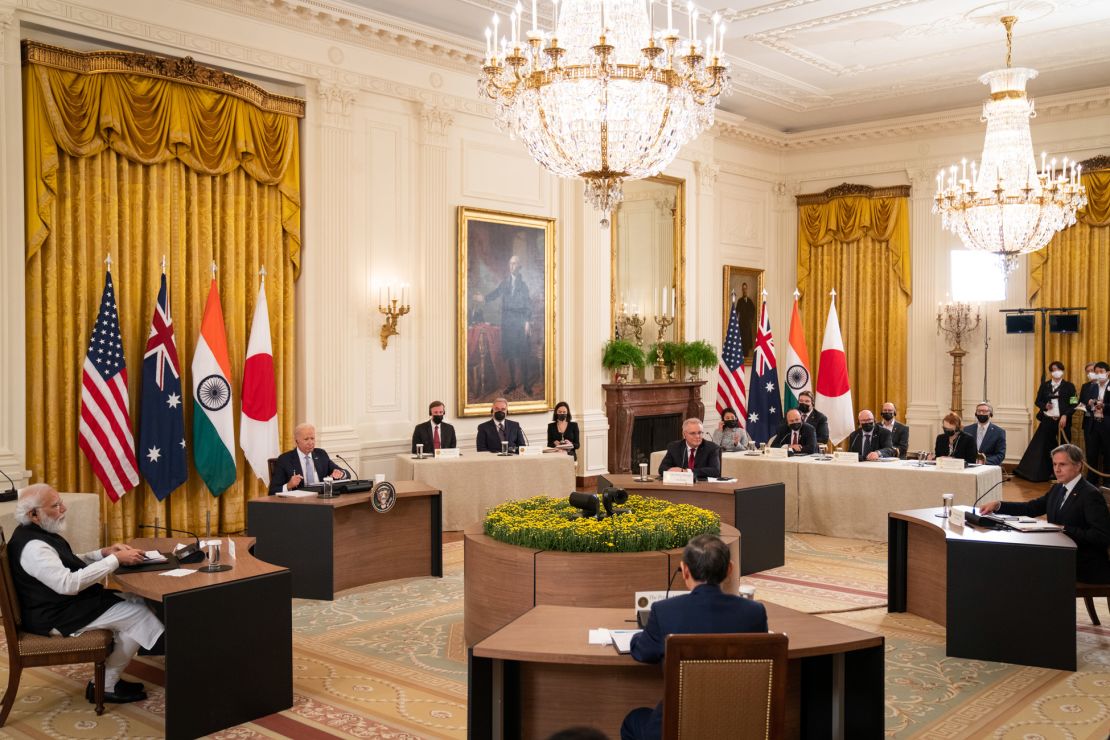

Convened around the mantra of promoting a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” the four countries have held two naval exercises since 2020. Their leaders have assembled three times since last year – including an in-person summit at the White House.

On Tuesday, the four leaders will meet face to face again in Tokyo. Their summit will be a highlight of Joe Biden’s first trip to Asia as the US President, as he seeks to strengthen alliances and partnerships to counter China’s growing influence in the region.

The renewed activity has seen China’s initial scorn turn into alarm, with Beijing viewing the grouping as part of Washington’s attempt to encircle the country with strategic and military allies. Wang, the foreign minister, has decried the grouping as an “Indo-Pacific NATO,” accusing it of “trumpeting the Cold War mentality” and “stoking geopolitical rivalry.”

That concern has only grown since the Ukraine crisis. Beijing’s backing of Moscow has further damaged its global image, leaving it more isolated on the world stage. And that is not helped by China’s insistence on a zero-Covid policy, in which stringent border restrictions are cutting the country off from a world that has largely moved on from the pandemic.

While Biden travels the world to reinforce ties, his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping hasn’t left China in 25 months. Biden’s latest flurry of diplomacy, with stops in South Korea and Japan, has particularly irked Beijing.

“The Indo-Pacific strategy cooked up by the United States, in the name of ‘freedom and openness,’ is actually keen on forming cliques,” Wang said Sunday as Biden wrapped up his trip to Seoul and headed to Tokyo.

“It claims that it intends to ‘change China’s surrounding environment,’ but its purpose is to contain China and make Asia-Pacific countries serve as ‘pawns’ of US hegemony,” Wang added.

But experts stress that the Quad is not an Asian NATO and neither does it aspire to become one. Instead, they say its flexibility as an informal forum allows it to build more partnerships and expand areas for cooperation – including on the new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework that Biden is expected to launch in Tokyo.

“The Quad is trying to emphasize that it has a positive agenda, which is much more about delivering what the Indo-Pacific region needs – versus becoming an anti-China, NATO-like entity, which is a reputation that it’s been trying very hard to combat in the region,” said Kristi Govella, deputy director of the Asia Program at the German Marshall Fund.

The driving force behind the Quad

China’s initial dismissal of the Quad was partly based on precedent.

A previous iteration of the Quad – proposed in 2007 by Japan’s then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – lasted barely a year due to a divergence of interests and pressure from Beijing. It crumbled in January 2008, when Australia announced its withdrawal from the grouping to pursue closer trade ties with China.

But the geopolitical and strategic calculus in the region has shifted drastically over the past decade. Under Xi, China has abandoned former leader Deng Xiaoping’s decades-old mantra of “hide your strength, bide your time.” Instead, it has pursued a more assertive foreign policy, readily flexing its economic muscle and military might.

A year after Xi took office, China started building – and increasingly militarizing – artificial islands throughout the contested waters of the South China Sea. It has increased its military posturing toward Japan, sending Chinese coastguard vessels into waters around the contested Senkaku Islands (known as the Diaoyu Islands in China) and flying warplanes into the airspace above.

Early in the pandemic, China imposed a flurry of trade sanctions on Australia after Canberra called for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid-19. And along its disputed Himalayan border with India, Chinese and Indian soldiers clashed in their deadliest conflict in four decades.

The tensions have driven these countries closer into the orbit of Washington, which under Biden has made the strategic rivalry with China a centerpiece of its foreign policy.

“The biggest driver of the Quad’s revival is the growing assertiveness and aggressiveness of China,” said Yuki Tatsumi, co-director of the East Asia Program at the Stimson Center.

“Its behavior not only in the East and South China Seas but also in the Indian Ocean all the way down around the Pacific island area resulted in bringing Quad countries’ perception of China closer together.”

As Beijing grows more distant from the West and its allies, it has moved ever closer to Moscow – but their “no limits” partnership has become more of a liability for China as Russia’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine draws global outrage.

“Beijing’s backing of Moscow reconfirmed the image of China as the disrupter of the existing international order that the countries in this region all have benefited – and continue to benefit – from,” Tatsumi said.

While the Quad has never explicitly mentioned China in public, it is hard to miss the thinly veiled references. Last September, when the four leaders met in person in Washington, they committed to “promoting?the free, open,?rules-based order, rooted in?international law and undaunted by coercion” – a clear rebuke to China’s increasingly aggressive behavior in the region.

In response, Chinese diplomats have repeatedly lashed out at the Quad for “disrupting regional peace and stability.”

Building “closed and exclusive small circles or groups is as dangerous as the NATO strategy of eastward expansion in Europe,” Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng said in March.

“If allowed to go on unchecked, it would bring unimaginable consequences, and ultimately push the Asia-Pacific over the edge of an abyss,” he said.

Not ‘Asia’s NATO’

NATO’s swift and coordinated response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has likely alarmed Beijing, say experts, who suggest its leaders are watching Western reaction to Ukraine with Taiwan in mind.

China views the self-governing democracy of Taiwan as a breakaway province and has not ruled out the use of force to achieve unification. Tensions between Beijing and Taipei are at the highest they’ve been in recent decades, with the Chinese military sending record numbers of war planes near the island – a show of force that is not lost on other countries in the region.

When the Quad leaders convened in March to talk about the Ukraine crisis, they agreed that “unilateral changes to the status quo with force like this should not be allowed in the Indo-Pacific region.”

But Jean-Pierre Cabestan, an expert on Chinese politics at Hong Kong Baptist University, stressed that the Quad is not a formal alliance like NATO.

“It can’t be Asia’s NATO. What structures the region’s security is a set of bilateral alliances concluded by the US after World War II – with Japan, South Korea, Australia and the Philippines. So there’s not such a thing as NATO in east Asia,” he said.

And unlike Japan and Australia, India is not a US ally – following a foreign policy tradition of non-alignment the country has adopted since independence.

There are structural differences too. Experts say in recent years the Quad has pivoted away from an overt focus on security issues to include more areas of cooperation, in an attempt to better address regional needs.

At their first virtual summit in March last year, the Quad leaders pledged to supply a billion Covid-19 vaccines across Asia by the end of 2022. The Quad has also formed working groups on climate change, technological innovation and supply-chain resilience.

During his trip to Tokyo, Biden is expected to unveil the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework – a long-sought plan to step up US economic engagement with the region. Experts say the framework could provide momentum for closer economic cooperation among the Quad countries – such as in infrastructure and supply-chain resilience.

In the eyes of Beijing, these efforts will likely be seen as a direct challenge. On Sunday, Wang, the Chinese foreign minister, said while China is always happy to see proposals conducive to regional cooperation, it is opposed to attempts to create division and conflict.

“Anyone attempting to isolate China with some framework will only isolate themselves. Rules made up to exclude China are bound to be abandoned by developments of our time,” he said.

But the Quad will need to demonstrate that it can deliver on its promises. Previous US attempts to boost economic ties with the region, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, have floundered, and the US will need to persuade potential allies and partners that it will stay committed to the region beyond Biden’s term.

Susannah Patton, a research fellow at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, said the Quad had already exceeded many analysts’ expectations. “The Quad is a vehicle for (its members) to present a different vision of how the region should work, and to signal to Beijing that it won’t have things its own way all the time,” she said.

“As for the future, how it evolves will in large part depend on China’s behavior. If China continues to undermine regional norms and coerce other countries, the Quad will respond.”

CNN’s Jessie Yeung contributed to this story.