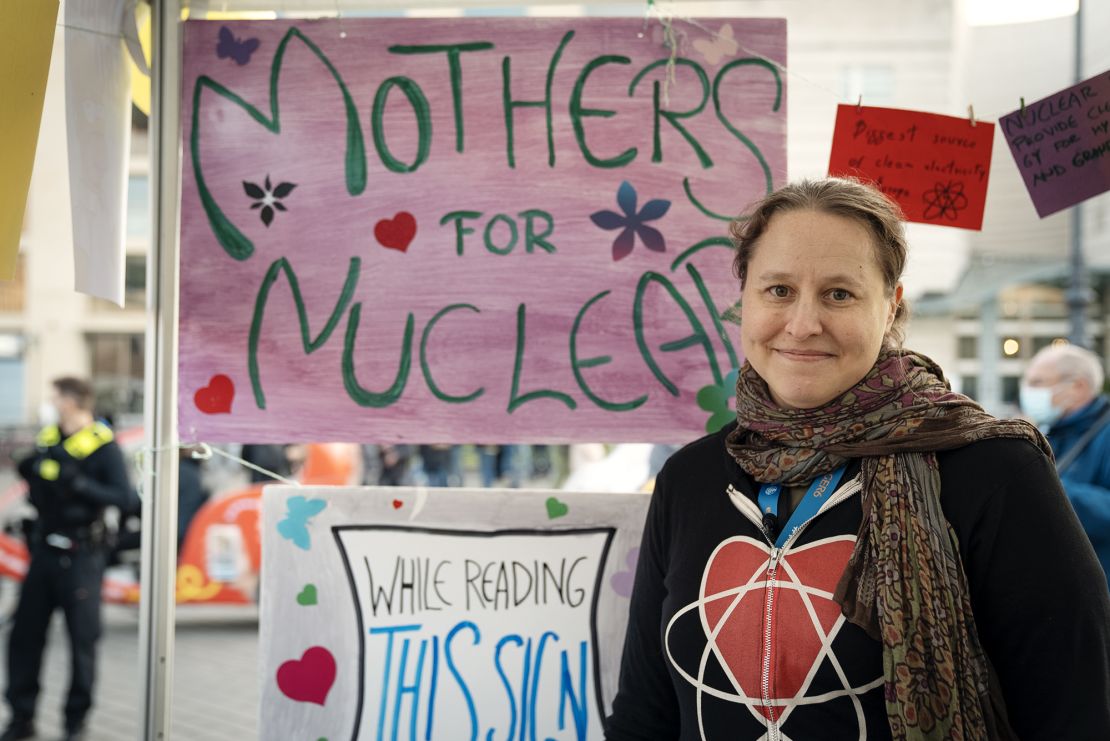

Growing up in Finland, Iida Ruishalme had a deep affinity for nature — particularly the forest, where she loved to go trekking with her dogs. Now, she’s worried that her daughters won’t experience such idyllic days as the climate crisis accelerates. So last month, she boarded a night train from Switzerland to join protests in the German capital Berlin.

Ruishalme agrees the world needs more wind farms and solar panels. But what she and her fellow demonstrators really want is a commitment to something else: nuclear energy.

“We have to give this technology a chance,” the Mothers for Nuclear member said, joining dozens of others who stood with signs outside the city’s famous Brandenburg Gate.

Nuclear power is one of the most reliable low-carbon sources of energy available, but memories of accidents at Fukushima, Chernobyl and Three Mile Island still loom large, fueling skepticism and fear and deterring investors from fundingnew projects.

Nuclear plants are also notoriously expensive to build. Construction tends to run over budget and time, and wind and solar energy has typically come out cheaper. How to safely store the radioactive waste it produces is another headache.

Germany began winding down its nuclear industry following the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan, when an earthquake and tsunami triggered a meltdown of three reactors in one of the worst nuclear incidents of all time. All six reactors still operating in Germany should be shut by the end of next year.

Yet the scale of the climate crisis is encouraging other governments and investors to give the nuclear industry another look.

Whether the world invests heavily into nuclear will depend on what people have the stomach for. Ruishalme, for one, hopes they’llput their anxieties aside.

“Our gut feelings don’t produce ready-made solutions,” she said, adding that she too once considered it “too risky,” but changed her mind after researching the pros and cons.

Europe’s big decision

Nuclear energy currently accounts for about 10% of the world’s electricity production. In some countries, the share is even larger. The United States and the United Kingdom generate roughly 20% of their electricity from nuclear energy. In France, it’s 70%, according to the World Nuclear Association.

The world is now at a nuclear crossroads: It could scale up nuclear as a sturdy energy source to keep emissions down, or throw all its money behind renewables, which are quicker to build and more profitable — but sometimespatchy.

Advocates emphasize that nuclear power flowseven when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow.

“We need renewables to be complemented by a reliable, 24/7 energy source,” said James Hansen, a climate scientist at Columbia University who also took part in the Berlin demonstration.

The UK government agrees. It supports the construction of the country’s first nuclear power station in more than two decadesin southwestern England. US President Joe Biden’s infrastructure package, meanwhile, includes $6 billion in grants to keep older plants running. And President Emmanuel Macron recently announced that France would begin building new plants for the first time in nearly 20 years.

That puts France and Germany at odds with each other ahead of a crucial decision by the European Union on whether to classify nuclear as “green” or “transitional” on a controversial list of sustainable energy sources set to be unveiled Wednesday. The outcome could unleash a wave of fresh funding, or leave nuclear on the outside.

EU climate chief Frans Timmermans recently indicated that both nuclear and natural gas — which is made up mostly of the greenhouse gas methane — could qualify for green financing.

“I think we need to find a way of recognizing that these two energy sources play a role in the energy transition,” he said at an event hosted by Politico. “That does not make them green, but it does acknowledge the fact that nuclear being zero emissions is very important to reduce emissions, and that natural gas will be very important in transiting away from coal into renewable energy.”

While nuclear power produces zero emissions when generated, the uranium required to make it needs to be mined, and that process emits greenhouse gases. Nonetheless, an analysis by the European Commission concluded that emissions from nuclear are around the same as wind energy and less than solar when the full cycle of production is taken into account.

Hansen, a longtime advocate for nuclear power, said it’s crucial in global efforts to decarbonize, and that Germany shouldn’t use its political clout to stand in the way of fresh investment.

“The consequence of treating it as not sustainable is we’re not going to have a pathway to limit climate change to the level that young people are now demanding,” he said. “It’s really important that Germany not be able to impose this policy on the rest of Europe and on the world.”

But German politicians and experts argue that high costs and the time it takes to build new plants — no fewer than five years, and often much longer — mean money would be better spent elsewhere.

The latest UN-backed climate science shows the world should nearly halve emissions over this decade to have any chance of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, a vital cap to avoid worsening climate impacts. The world must also shoot for net zero by mid-century. That means emissions must be reduced as much as possible, and the rest captured or offset.

Current pledges, including those made at the recent COP26 climate summit in Scotland, onlyget the world around one-quarter of the way there, according to Climate Action Tracker.

The International Energy Agency says that nuclear power generation shouldmore than double between 2020 and 2050 in the pursuit of net zero. Its share in the electricity mix will drop, but that’s because demand for power will soar as the world electrifies as many machines as possible, including cars and other vehicles.

Yet Ben Wealer, who researches nuclear power economics at the Technical University of Berlin, argues that the world can’t waitfor new nuclear plants, especially since the next eight years are so crucial to decarbonizing.

“Looking at the time frames, it cannot be a huge help in combating climate change,” he said. “It blocks the cash we need for renewables.”

Even if the world did have more time, delays are a problem. The Hinkley Point C plant in the United Kingdom, for example, is now to be completed in mid-2026, six months later than planned, and its costs are rising. The latest price tag was as much as £23 billion ($30 billion), about £5 billion ($6.6 billion) more than when the project was launched in 2016.

German officials also argue that the lack of a global plan for storing toxic waste should disqualify nuclear as a “sustainable” energy source.

Christoph Hamann, an official at Germany’s federal office for nuclear waste management, emphasized that government efforts to construct sites below ground where waste can be stored indefinitely remain a work-in-progress.

“We’re talking about a very toxic, high radioactive waste, which is producing problems for the next tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of years. And we’re directing this problem, when using nuclear power, to future generations,” Hamann said.

Wave of funding

It’s not just Europe that’s mulling more nuclear. The most energetic push is in China, where there are 18 reactors under construction as the world’s biggest emitter tries to pivot away from coal. That’s more than 30% of the reactors being built globally, according to the World Nuclear Association.

And the debate is becoming more complex as new nuclear technologies are developed and show signs they could generate better financial returns.

The US government has backed TerraPower, the startup chaired by Bill Gates. The company, which wants to stand up a next-generation nuclear project at a former coal hub in Wyoming, utilizes molten salt to transfer heat from the reactor and use it to generate electricity, which it claims will simplify construction and allow it to adjust output to meet changing demand.

Meanwhile, Britain is supporting a push by engineering firmRolls-Royce to build smaller nuclear reactors, which have lower upfront costs. That pitch could help draw in private investors.

“It’s very, very difficult for any country to achieve net zero ambitions without nuclear,” said Tom Samson, the CEO of the new Rolls-Royce venture.

The parts of a Rolls-Royce reactor are designed so almost all of it can be built and assembled in a factory. That limits the amount of time that’s required to piece its components together on an expensive construction site. Initially, production is estimated at £2.2 billion ($2.9 billion) per unit.

“If you look back in history, you can find lots of examples of big nuclear projects that have struggled,” Samson said. “We’ve designed ours to be different.”

About £210 million ($278 million) in funding from the UK government will allow the company to begin applying for regulatory approvals. It hopes to set up three factories in Britain and start churning out about two units per year, which would power 2 million homes. The first unitis expected to go into service in the United Kingdom in 2031.

For comparison, theHinkley power station is expected to provide electricity for 6 million homes.

Samson also emphasizes that smaller reactors produce little waste. The spent fuel from a small modular reactor operating for 60 years would fill an Olympic-size swimming pool, he said.

Fission or fusion?

According to data from PitchBook, nuclear energy startups raised $676 million in venture capital funding globally in the first nine months of 2021. That’s more than the total amount raised over the past five years combined.

That figure includes funding for startups that explore nuclear fusion, which has been attracting more attention. The nuclear power generators currently operating use fission technology, which involves splitting the nucleus of an atom. Fusion is the process of combining two nuclei to create energy — often referred to as the energy of the sun or the stars.

Scientists are still working out how to successfully manage a fusion reaction and turn it into a commercially viable project. But investors are increasingly excited about its potential since it doesn’t produce lingering radioactive waste and comes with no risk of a Fukushima-style meltdown, nor does it rely on uranium.

Helion, a US-based fusion startup, announced last month that it had raised $500 million in a round led by Sam Altman, the former president of Y Combinator.

As the world weighs which way to turn on nuclear, it could be years until it’s clear which was the right road to take. A look at Germany and France in 10 or 20 years from now may provide the answer.

Ultimately, arguments around emissions, reliability and economics may be cast aside. The real future of nuclear could come down to public opinion.

“If there is a nuclear accident, a new major one, that could kill the entire industry,” said Henning Gloystein, director of energy, climate and resources at Eurasia Group.

— Xiaofei Xu contributed reporting.