Supreme Court justices tout judicial integrity and the importance of public confidence in their decisions, but the court’s midnight silence Tuesday while letting a Texas law that curtails abortion rights take effect – followed by a midnight order Wednesday – offers the latest and most compelling example of its lack of transparency and the cost.

The justices’ secretive patterns have gained new attention as confidence in all government institutions has waned. Witnesses before a bipartisan commission set up by President Joe Biden to consider court revisions – most visibly, the options of term limits and the addition of more seats – have targeted the justices’ secrecy and how it contributes to public distrust of the high court, along with the lopsided advantage the court gives to some litigants.

Such lack of transparency is only part of the context behind the Supreme Court’s silence in the closely watched Texas case. The emboldened conservative majority already is poised to reverse or at least undercut Roe v. Wade, the 1973 landmark ruling that declared women’s constitutional right to end a pregnancy. The court announced last spring that it would take up in the 2021-22 session a dispute over Mississippi’s ban on abortions after 15 weeks. The Texas law goes much further, making it illegal to terminate a pregnancy when a fetal heartbeat is detected, which may be typically around six weeks.

Both laws sharply conflict with Roe v. Wade, which forbade states from interfering with a woman’s abortion decision before the fetus would be viable, that is, able to live outside the womb, at about 22-24 weeks.

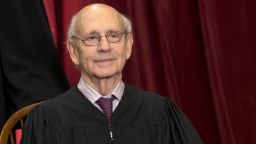

The justices have made plain their concerns regarding public mistrust and misunderstanding of the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Roberts regularly declares that judges differ from elected lawmakers, and Justice Stephen Breyer protested in a speech at Harvard last spring that they should not be regarded as “junior-varsity politicians.” Breyer cited the court’s long-standing preservation of abortion rights as evidence of its nonpartisan, nonideological character.

Separately last spring, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Neil Gorsuch emphasized in a joint appearance, advocating civics education, the deep reasoning that underlies their opinions. They criticized those who would look only for a bottom-line judgment.

Yet no judgment – or word of any sort – came late Tuesday night, with the clock ticking, anxiety rising among both sides in Texas and a national audience watching.

There was no avoiding the sense that the justices had abdicated some responsibility. The Supreme Court has the last word on the law under the US Constitution. If Roe v. Wade were suddenly invalid in Texas or elsewhere, it would be for the court to declare, traditionally in a signed opinion.

Amid the confusion, some advocates on both sides took Tuesday night’s silence as implicit endorsement of the law.

At midnight Wednesday, a 5-4 court said it would not block the Texas law, nearly 24 hours after it already had taken effect and has already severely curtailed abortion access in the country’s second-largest state.

The shadow docket

The entire ordeal has highlighted the Supreme Court’s secretive operations, particularly for scores of important cases handled outside of the usual pattern of scheduled oral arguments.

The justices decline to make their votes public or offer reasoning on many cases that arise on what’s become known as “the shadow docket.”

Even on cases that result in public orders, such as those last week rejecting the Biden administration’s policy on US asylum-seekers and a Covid-19 eviction moratorium, the justices do not make their votes explicit.

It appeared in both cases that all six conservatives had joined the majority, but that was not clear. Only the three liberals – Breyer, Sotomayor and Elena Kagan – publicly dissented. In an earlier stage of the moratorium dispute this summer, Roberts had fully voted with the liberals to allow a temporary freeze on evictions to continue.

The justices’ opinion invalidating the Biden administration freeze on evictions, based on the reasoning that only Congress could impose such a moratorium, was unsigned.

Patterns of ambiguity and secrecy extend to the justices’ personal behavior, too. If any of them sit out a dispute because of a conflict of interest, they decline to explain it. When they are injured and land in the hospital, they often keep that quiet, too. Last year, Roberts fell while at a country club near his suburban Maryland home, hit his head and was rushed to a hospital by ambulance. He declined to make the June incident public for more than two weeks, and then only after The Washington Post followed up on a tip.

A related topic that has been the subject of the Biden overhaul commission: The nine refuse to be bound by federal judicial ethics rules that cover lower court judges. They also decline to provide advance notice of their expense-paid travels to academic and special interest organizations for speeches. And they give scant information about book or other extracurricular deals they have signed.

The most recent case in point: Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s reported $2 million book deal negotiated soon after she took her seat in 2020. Her publisher has confirmed that an agreement exists but declined to provide any details about the book subject or what it is paying Barrett. She did not respond to news media questions about the deal.

Such tendencies are hardly new. Nor is the justices’ desire to further their own stature through mystique and mystery. But today’s trend may be having the opposite effect when it comes to public regard. Gallup reported in July that Americans’ approval of the Supreme Court had fallen to 49%, the first such below-50% rating since 2017 and a contrast to its 2020 poll that found 58% of Americans approved of the court.

Equally important, the drama over the Texas case demonstrates the confusion for Americans when the justices fail to act with clarity.

Why the format matters

Abortion access has been at the heart of politics surrounding the Supreme Court for decades. The issue has driven debate in presidential elections, control of Congress and, especially, Senate confirmation hearings over Supreme Court candidates. That makes the manner in which the court has acted – or failed to act – all the more startling. As the justices themselves often state, the public looks to fair processes and procedures, as well as the substance of decisions, for confidence.

For decades, the Supreme Court solidly upheld the right to abortion, including in a milestone 1992 case from Pennsylvania. After that, for nearly 30 years, the justices sidestepped appeals that would have threatened the basic principles of Roe v. Wade. They heard disputes testing regulations on clinics but never reexamined the core abortion right before viability.

Some justices denounced that pattern. Justice Neil Gorsuch, former President Donald Trump’s first appointee, wrote last year that in a “highly politicized and contentious arena … we have lost our way.” Justice Clarence Thomas, who has served since 1991, longer than any current justice, has been the most consistent critic of Roe and written, “Our abortion jurisprudence has spiraled out of control.”

When the justices announced last spring that they would hear in the 2021-22 session the Mississippi controversy over a law banning abortion at 15 weeks, it appeared that the viability line might dissolve. That case will be subject to full briefing and oral arguments before a ruling likely by the end of June.

The current Texas ordeal is a wholly different matter, coming to the justices without full briefing and subject to vague rules and procedures.

Complicating matters, Texas lawmakers wrote the prohibition to evade traditional legal challenge. The measure specifically prevents the state attorney general and health officials from enforcing the law. Rather, it creates a right for private citizens to sue anyone who assists a pregnant woman who seeks an abortion after six weeks. If successful, the private citizen could obtain $10,000 in damages.

This novel legal mechanism has roiled the lower court action in the challenge brought by Whole Woman’s Health and other abortion clinics in Texas. A US district judge had scheduled a hearing in the dispute, but the 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals prevented the lower court’s action and paved the way for the law to take effect on its September 1 schedule – barring Supreme Court intervention.

Whole Woman’s Health submitted an emergency petition to the justices on Monday. Capturing the chaos in Texas, the lawyers described in another filing on Tuesday women waiting in clinics, concerned that their ability to obtain scheduled abortions would evaporate. Among them, according to the filing, was a minor who had obtained permission from a judge for an abortion but could not be seen at a clinic on Tuesday. “(B)ecause she is close to the legal limit for accessing abortion in Texas,” the challengers told Supreme Court justices, “if she does not obtain care in the next day or two, she will be barred from accessing her right to abortion in Texas.”

Over objections from Texas officials that the clinics lacked any grounds to sue state officials, the clinics implored the justices to block “Texas’s flagrant defiance” of the justices’ own precedents: “At bottom, the question in this case is whether – by outsourcing to private individuals the authority to enforce an unconstitutional prohibition – Texas can adopt a law that allows it to do precisely that which the Constitution forbids.”

Wednesday night, the court let the law stand, but also let the overall confusion fester, a result of the shadow docket process, Justice Elena Kagan wrote in a dissent.

“Today’s ruling illustrates just how far the Court’s ‘shadow-docket’ decisions may depart from the usual principles of appellate process,” Kagan wrote. “That ruling, as everyone must agree, is of great consequence. Yet the majority has acted without any guidance from the Court of Appeals – which is right now considering the same issues. It has reviewed only the most cursory party submissions, and then only hastily. And it barely bothers to explain its conclusion – that a challenge to an obviously unconstitutional abortion regulation backed by a wholly unprecedented enforcement scheme is unlikely to prevail.

“In all these ways, the majority’s decision is emblematic of too much of this Court’s shadow docket decision-making – which every day becomes more un-reasoned, inconsistent, and impossible to defend.”

This story has been updated after the court’s action Wednesday night.